|

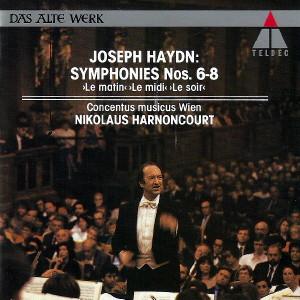

1 CD -

2292-46018-2 - (p) 1990

|

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie Nr. 6 D-dur "Le

Matin", Hob. I/6 |

|

22' 15" |

|

- Adagio - Allegro

|

6' 06" |

|

1

|

| - Adagio

- Andante |

7' 23" |

|

2

|

| - Menuetto - Trio |

4' 17" |

|

3

|

| - Finale. Allegro |

4' 29" |

|

4

|

| Symphonie

Nr. 7 C-dur "Le Midi", Hob. I/7 |

|

25' 05" |

|

- Adagio - Allegro

|

8' 09" |

|

5

|

| - Recitativo - Adagio |

9' 05" |

|

6

|

- Menuetto - Trio

|

3' 37" |

|

7

|

- Finale. Allegro

|

4' 14" |

|

8

|

| Symphonie

Nr. 8 G-dur "Le Soir", Hob. I/7 |

|

24' 51" |

|

| - Allegro molto |

5' 35" |

|

9

|

| - Andante |

11' 41" |

|

10

|

| - Menuetto - Trio |

3' 11" |

|

11

|

| - Presto "La Tempesta" |

4' 24" |

|

12

|

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria) - giugno

1989 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 2292-46018-2 - (1 cd)

- 72' 38" - (p) 1990 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Experimental Music, Anno

1761

|

Haydn’s trio of "imes

of the day” symphonies

was written in 1761: Symphonies

no. 5 “Le Matin”,

no. 7 “Le

Midi” ana no. 8 "Le Soir” show clearly

the hand of the twenty-nine-year~old

composer. Are these just early

attempts of Haydn to find his

symphonic feet, then? The

insignificant work of

a beginner in the

genre? Or even a commission obediently

executed for his employer, Prince

Esterházy? No

indeed, they are nothing af

the sort! On the

contrary, Symphonies nos. 6-8 shaw the

unrestrainable delight in experiment

at a creative young man who "pulls out

all the stops” here. These three

symphonies tell an exciting story,

which we retell here in leaps and

bounds.

On 1st May 1761, Joseph Haydn signed a

contract numbering fourteen

items, which bound him to the court at

Prince Paul Anton Esterházy in Eisenstadt

as "domestic officer".

Haydn, hitherto under contract

ta Count Morzin,

could not as yet guess that this

decree at 1761 would detain him at the

Esterházy court for

the best part of

thirty years. First of

all, he studied - with dn

understandable degree at excitement -

the new rights and duties attached to

his position as the newly-appointed

deputy Kapellmeister.

He was to make music, ta supervise the

musicians, to convey

any disagreements with the latter to

the Prince for him to decide on; he

was expected to keep the singers at

their best, to take care of

the instruments at the orchestra and

provide for the copying

of sheet music as

required, and, last but not least, -

thus the fourth item in

his contract - he was to compose whatever

was demanded of him

at all times:

"4. At the

supreme command of His Serene Royal

Highness, the Deputy Kapellmeister is

required to compose such works

of music as His Highness shall demand;

he shall

communicate with no-one with regard to

these compositions, and shall under

no circumstances allow them to be

copied, but shall reserve them

for the exclusive pleasure of His

Highness. In

particular: he shall not compose

music for anyone else without the

prior knowledge and consent of His

Highness.”

In present-day terms, Haydn

entered into an exclusive contract,

and he was bound to secrecy as well.

He was rewarded with annual emoluments

of 400 Rhineland guilders;

and he received a further,

non-material reward inthe shape of

Prince Paul Anton's passionate love of

music - an enthusiasm that was

surpassed by that of his successor

Prince Nikolaus Esterházy,

who became regent in l762. Employers

who loved and had an understanding of

music, and noble conditions of

employment: Haydn had struck lucky.

And fortune smiled on him for the rest

ot his lang life, towards the end of

which he wrote to his biographer Griesinger

expressing his gratitude to the Esterházy

family:

"My employer was satisfied with

everything I

produced; I received

applause and praise; as the director

of the orchestra I was allowed

to experiment and to observe what made the

desired impression and what

detracted from it - i.e. I had the

chance to improve, to make additions

and cuts, to take risks. I was

isolated from the world; there

was no-one nearby ta confuse or

irritate me, and so I had no choice

but to be original. ”

This summing-up of Haydn's career can

effortlessly be applied to the “times

of the day” symphonies. Here, Haydn

certainly did experiment and observe,

trying out ditterent

effects and juggling with different

styles. And in his experimentation,

paradoxical as it may sound, he looked

towards both the past and the future

at the same time. How come? Haydn

seems to have been familiar with the

basic wisdom of modern creativity

psychology, for he knew intuitively

that musical progress is borne on the

shoulders of composing tradition: the

composer who wants to make new

discoveries must study the scores of

his predecessors first of all, he must

be able to learn them and play them

himself. But we really ought to be

telling the story in the right order:

Haydn first set about the task of

reorganising the orchestra. He

enlarged the modest ranks of Prince Esterházy's

existing band (3 violins, l cello, 1

double-bass) by the addition of a flute,

two oboes, two bassoons and two horns,

and the body of strings was increased

in size too. Furthermore, we can

assume that the idea ot depicting the

times of the day in music came from

Prince Esterházy himself;

Haydn's

predecessor in the post, Gregor

Werner, had already composed a

"Musical instrumental calendar” circa

1740. And it's also helpful to know

that the Prince's collection of

scores included a large number of

Italian concerti -

concerti grossi by

Vivaldi, Tartini,

Valentini,

Albinoni and others testify

to the Princes fondness for the

italian concertante style. In

other words, Haydn had to take two

main things into account: the Prince’s

personal taste on the one hand, and

the new orchestra with solo woodwind

on the other. Hence the Symphonies

nos. 6-8 are actually concerti in

disguise: orchestral tutti alternate

throughout with concertino sections,

i.e. with solo ensembles. Haydn

skilfully combines the expansive

orchestral sound developed in the

Mannheim School with the traditional

development technique of

early origin, and arrives at his own

specitlc treatment of an “open-work”

style of composition

via this synthesis of historic and

contemporary elements. Another

circumstance that influenced the

symphonies was the participation of

virtuoso soloists in the Esterházy

orchestra. Thus the demanding solo

parts in Symphony no. 7 were written

for the violinist Tomasini,

while the tricky cello solos in the

finale of Symphony no. 6 and in the

adagio of no. 7 were a

gesture of affection for

Haydn’s friend Weigl, the principal

cellist at Esterházy. In

tact, it is not going too far

to say that Haydn’s concept of a new

type of symphony as a "concerto grosso

in symphonic form” brings out the wind

instruments in such prominent and

virtuoso manner, that a musical genre

of the future

is thus established: the sinfonia

concertante.

Looking back to the past, anticipating

whats to come: Haydn alternates

constantly between these two

strategies here. In the slow

introduction of the first

movement of Symphony no. 7, for

example, he has recourse to tradition,

with the pathetic and rhythmic spirit

of an old French overture being

conjured up; the programmatic

introduction to the Sixth, on the

other hand, brings a look ahead, with

the sun rising in musical form as it

was to do 37 years later in "The

Creation". "La Tempesta", a musical

depiction of a storm like that in

Vivaldi's E flat major concerto op.

8/5, takes us back again to tradition,

while the balanced chamber-music

"conversation" in the andante of no. 8

once again anticipates what lies

ahead. Here, Haydn creates the model

of a "musical discourse", with formal

sense of order and rhetoric nuances of

expression counterbalancing each other

in the manner that the philisophers of

the Enlightenment - Lessing,

Gottsched, Bodmer and Baumgartner -

viewed as the principle of a new kind

of art. The alternation of solo and

tutti in all three symphonies is

backward-looking in character, but the

solo bassoon line (the trio in the

minuet of no. 6), or the solo

double-bass (in the trio of the minuet

of no. 8) are clearly forward-looking.

Likewise forward-looking is the

fully-composed cadenza in the adagio

of Symphony no. 7: here, Haydn no

longer leaves the interplay of forces

up to improvisation, but determines

the relationship between thematic

substance and playful décor himself.

The traditional harmony and modulation

plans are undoubtedly

backward-looking, but harmonic attacks

such as in bars 87-92 of the first

movement of no. 7, where F major

suddenly veers off into the remote key

of B major, anticipate future

evelopments. Ket's return once more to

the rarity in the Symphony no. 7, the

slow movement. Haydn (one is almost

tempted to say: in bold

anticipation of Scumann or Liszt)

writes a "recitativo" in which the

solo violin develops the ability to

speak freely - what Schönberg was later to

coin the term "musical prose" to

describe. Haydn follows this with an

instrumental aria, a vocal Konzertstück which he then

rounds off in logical consistence

with the above-mentioned written-out

cadenza together with the orchestral

closing formula that comes after it.

Operatic drama and operatic

declamation: the 29-year-old

deputy Kapellmeister at

Eisenstadt even dares to try his hand

on this as yet unfamiliar territory.

Haydn cannot yet know Lessing's

"Hamburgische Dramaturgie" of 1769,

but he is already in the position to

realise Lessing's innovatory demands:

"In vocal music the text

offers far too much

support to the espression...

where-as this help is lacking in

instrumental music. Here, then,

the artist will have to employ

his utmost strenght; he will

only select from the sequences

of notes able to express a

feeling those that express it

most clearly."

Let's take a curious example: at

the opening of the adagio of

Symphony no. 6, the strings (= a

school class early in the

morning?) play a G major scale and

end up on the wrong note, B

flat; they are energetically

corrected by the solo violin (the

teacher?), which

points out that last note should

be B. An amusing little scene,

depicted in music of the "utmost

strength". Experimental music,

then, at a point when new rules

have not yet been drawn up.

Haydn brings everything together

that falls into his inquisitive hands: the old

concerto principle and the new

solo style of the symphony;

the old minuet and the modern

instrumental recitative; C. P.

E. Bach's or Gluck's "fiery"

style (compare the similarity

between Don Juan's journey to

Hell and the first movement of

Symphony no. 7) and the

Enlightenment manner of a

balanced debate (cf. the

andante of no. 8). Aged only

29, Haydn was lucky: he ended

up in the right place at the

right time, in the service of

the right man. Prince Esterhãzy

pushed the flexible young

composer forwards and made him

take heed of tradition at one

and the same time. And with

"his" new orchestra, Haydn had

the right framework for

experimenting. Capable

soloists were a challenge that

he responded to without

hesitation. And thus it was

that the year 1761 gave birth

to experimental music: Haydn's

lively mind found the new

musical territory just as

exciting as the old ground,

and couldn't resist exploring,

comparing, combining and

synthesizing. That is the

story that these three

symphonies tell: the story of

a model of musical progress

that has lost none of its

currency to the present day.

In other words:

the right conditions tor experimenting

have to exist, there has

to be suitable “moterial” for

experimenting on (and

that includes trodition,

of necessity), and of

course a mind

that loves to experiment

- and is given scope to

do so. Haydn had this sort

of mind - and

nothing does his boundless creative

genius greater injustice

than the cosy old image, full

of prejudice and

condescension, of “Papa

Haydn”.

Hans-Christian

Schmidt

Translation: Clive R. Williams

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|