|

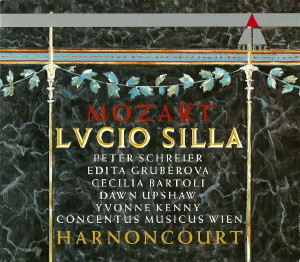

2 CD -

2292-44928-2 - (p) 1990

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lucio Silla, KV 135 |

|

|

|

| Dramma per

musica in tre atti - Libretto: Giovanni de

Gamerra |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Overtura |

|

7' 34" |

|

| - Molto

Allegro |

3' 37" |

|

CD1-1 |

| - Andante |

2' 32" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Molto

Allegro |

1' 25" |

|

CD1-3 |

| Atto Primo |

|

63' 18" |

|

| -

Recitativo: "Oh ciel, l'amico Cinna" -

(Cecilio, Cinna) |

2' 21" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - No. 1

Aria: "Vieni, ov'amor t'invita" - (Cinna) |

7' 40" |

|

CD1-5 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Dunque sperar poss'io" -

(Cecilio) |

2' 44" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - No. 2

Aria: "Il tenero momento" - (Cecilio) |

8' 08" |

|

CD1-7 |

| -

Recitativo: "A te dell'amor mio" - (Silla,

Celia) |

1' 27" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - No. 3

Aria: "Se lusinghiera speme" - (Celia) |

5' 42" |

|

CD1-9 |

| -

Recitativo: "Sempre dovrò vederti" -

(Silla, Giunia) |

1' 52" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - No. 4

Aria: "Dalla sponda tenebrosa" - (Giunia) |

6' 09" |

|

CD1-11 |

| -

Recitativo: "E tollerare io posso" -

(Silla) |

0' 22" |

|

CD1-12 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Mi piace! E il cor di

Silla" - (Silla) |

1' 11" |

|

CD1-13 |

| - No. 5

Aria: "Il desio di vendetta" - (Silla) |

5' 10" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - Andante |

0' 49" |

|

CD1-15 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Morte, morte fatal" -

(Cecilio) |

4' 52" |

|

CD1-16 |

| - No. 6

Coro: "Fuor di queste urne" - (Giunia,

Coro) |

5' 57" |

|

CD1-17 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Se l'empio Silla" -

(Giunia) |

2' 20" |

|

CD1-18 |

| - No. 7

Duetto: "D'esilio in sen m'attendi" -

(Giunia, Cecilio) |

6' 24" |

|

CD1-19 |

Atto Secondo

|

|

50' 31"

|

|

| -

Recitativo: "Io ti scopro" - (Silla,

Celia) |

2' 41" |

|

CD1-20 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Cecilio, a che t'arresti" -

(Cecilio) |

4' 01" |

|

CD1-21 |

| - No. 9

Aria: "Quest'improvviso trèmito" -

(Cecilio) |

2' 47" |

|

CD2-1 |

| -

Recitativo: "Silla m'impone" - (Giunia,

Cinna) |

1' 47" |

|

CD2-2 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Vanne. T'affretta" -

(Giunia) |

1' 26" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - No. 11

Aria: "Ah se il crudel periglio" -

(Giunia) |

8' 02" |

|

CD2-4 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Ah sì, scuotasi omai" -

(Cinna) |

0' 39" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - No. 12

Aria: "Nel fortunato instante" - (Cinna) |

3' 45" |

|

CD2-6 |

| -

Recitativo: "Giunia? Qual vista!" -

(Silla, Giunia) |

1' 27" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - No. 13

Aria: "D'ogni pietà mi spoglio" - (Silla) |

1' 59" |

|

CD2-8 |

| -

Recitativo: "Che intesi eterni Dei?" -

(Giunia, Cecilio) |

1' 34" |

|

CD2-9 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Chi sà, che non sia questa"

- (Cecilio) |

1' 00" |

|

CD2-10 |

| -

Recitativo: "Perchè mi balzi in seno" -

(Giunia, Celia) |

1' 21" |

|

CD2-11 |

| - No. 15

Aria: "Quando sugl'arsi campi" - (Celia) |

6' 49" |

|

CD2-12 |

| -

Accompagnato: "In un istante" - (Giunia) |

3' 27" |

|

CD2-13 |

| - No. 17

Coro: "Se gloria il crin ti cinse" -

(Coro) |

2' 22" |

|

CD2-14 |

| -

Recitativo: "Padri coscritti" - (Silla,

Giunia, Cecilio) |

1' 56" |

|

CD2-15 |

| - No. 18

Terzetto: "Quell'orgoglioso sdegno" -

(Silla, Giunia, Cecilio) |

3' 30" |

|

CD2-16 |

| Atto Terzo |

|

32' 34" |

|

| -

Recitativo: "A lui t'afretta" - (Cinna,

Celia) |

1' 13" |

|

CD2-17 |

| - No. 19

Aria: "Strider sento la procella" -

(Celia) |

4' 03" |

|

CD2-18 |

| -

Recitativo: "Più non mi resta" - (Cecilio,

Cinna) |

0' 45" |

|

CD2-19 |

| - No. 20

Aria: "De' più superbi il core" - (Cinna) |

6' 42" |

|

CD2-20 |

| -

Recitativo: "An nò, ch'l fato estremo" -

(Cecilio, Giunia) |

1' 55" |

|

CD2-21 |

| - No. 21

Aria: "Pupille amate" - (Cecilio) |

5' 07" |

|

CD2-22 |

| -

Accompagnato: "Sposo, mia vita" - (Giunia) |

3' 07" |

|

CD2-23 |

| - No. 22

Aria: "Fra i pensier più funesti" -

(Giunia) |

3' 20" |

|

CD2-24 |

| -

Recitativo: "Roma, e il senato" - (Silla,

Giunia, Cecilio, Cinna, Celia) |

2' 59" |

|

CD2-25 |

| - No. 23

Finale - (Silla, Giunia, Cecilio, Cinna,

Celia, Coro) |

3' 23" |

|

CD2-26 |

|

|

|

|

| Peter Schreier,

Lucio Silla |

|

Edita Gruberova,

Giunia

|

|

Cecilia Bartoli,

Cecilio

|

|

Dawn Upshaw,

Celia

|

|

Yvonne Kenny,

Cinna

|

|

|

|

| Arnold Schönberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Leitung |

|

| Continuo: Herbert

Tachezi, Cembalo |

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violine |

-

Charlotte Geselbracht, Viola |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

-

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Rudolf Leopold, Violoncello |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

-

Robert Wolf, Flauto traverso |

|

| -

Silvia Iberer, Violine |

-

Sylvie Summereder, Flauto

traverso

|

|

| -

Peter Matzka, Violine |

-

Omar Zoboli, Oboe |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus, Violine |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Christine Busch, Violine |

-

Milan Turković, Fagott |

|

| -

Peter Katt, Violine |

-

Stepan Turnovsky, Fagott |

|

| -

Herlinde Schaller, Violine |

-

Eric Kushner, Horn |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violine |

-

Alois Schlor, Horn |

|

| -

Jaqueline Roschek, Violine |

-

William Nulty, Trompete |

|

| -

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

-

Edward Czervenka, Trompete |

|

| -

Lila Brown, Viola |

-

Michael Vladar, Pauken |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Konzerthaus,

Vienna (Austria) - 4 & 6 giugno 1989 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 2292-44928-2 - (2 cd) - 77' 44" + 76'

47" - (p) 1990 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Heroic opera

through youthful eyes

|

When the management of

the Regio Ducal Teatro in Milan (the

forerunner of the Scala) asked Mozart

to compose the first of two operas

planned, in accordance with tradition,

for the Carnival season of 1772/73, it

was a very prestigious commission for

the barely 15-year-old composer.

The contract of 4th March 1771 laid

down the customary conditions of

employment. Mozart was to enjoy a

furnished apartment for the duration

of his stay in Milan and to receive

for his artistic efforts ("virtuose

fatiche") which, in addition to

composition, were to include

rehearsals and the over all musical

direction, an honorarium which, though

reasonable, was certainly not over

generous. In return he was required to

deliver the recitatives for the opera

by early October 1772 and to present

himself in Milan by the beginning of

November, in order to set the arias to

music (in consultation with the

singers) and to assist with the

rehearsals. Since the premiere was

fixed for 26th December 1772, a bare

three months were available for all

the preparations including the actual

composition. Indeed, there was even

less time because Mozart, on whom the

main burden fell, did not arrive in

Milan with his father Leopold until 4th

November, and the principal singers

still later, towards the end of

November or the beginning of December.

Most of the main numbers were not even

ready until December, by which time

the rehearsals had already begun.

Finally, at the beginning of December

the title role had to be recast,

because the tenor who had been engaged

fell ill. Obviously Mozart was very

pressed for time; one can only marvel

at the professionalism and presence of

mind of everyone involved in working

at such speed - and this was by no

means a unique occasion.

A postscript to a letter of Mozart’s

of 5th December speaks

for itself in its customary refreshing

spontaneity: "Now I have got 14

numbers to write [14 (actually 12)

numbers out of a total of 23], and

then I am finished,

although one can count the Trio (No.

18) and the Duet (No. 7) as 4 numbers.

It is impossible for

me to write much, because I don’t know

what to say and secondly I

don't know what I am

writing, for I cannot think about

anything except my opera and am

in danger of writing a whole aria to

you instead of words."

But these conditions were quite normal

in the operatic culture of that time.

There was no repertoire to fall back

on. In renowned

theatres, at least, the public always

demanded to see and hear

something new. Even reasonably

successful operas rarely survived

beyond their first production. The

only enduring elements in this hectic

situation were the

opera texts (e.g. Metastasio’s dramas)

which were constantly being reset

to music, and the conventions

which governed the music, the staging

and the highly complex interplay of

everyone involved in an operatic

production. Although the music got the

lion’s share in terms of effort, it

was valued (perhaps to an exaggerated

degree, viewed from our modern

standpoint) primarily as a component

in the performance as a

whole, as part of the production. In

this respect it was less the quality of

the composition which was

decisive for success than the

reputation and performance

of the singers. Under these

conditions it was not economically

practicable to rehearse a

new opera for longer than a few weeks.

Composers and singers who wanted to

stay in business and to achieve

standing and reputation had to adapt

themselves to these conditions.

Bearing this in mind one can only be

astonished at the standard of text,

music and performance which was

usually achieved, in spite of the

truly murderous state of affairs in

the world of opera.

Mozart was able to meet these demands,

although at the time he set out to

compose "Lucio Silla" he

was hardly regarded by his

contemporaries as an experienced

operatic composer. But he certainly

was in no way inferior in terms of

reliable, complete and easy mastery of

the craft to experienced and famous

colleagues such as G. Paisiello, J. C.

Bach, G. Galuppi or N. Jommelli. As

has already been pointed out, the

opera commission (the “scrittura") for

Milan was all the more prestigious as

Mozart was certainly not an operatic

composer with an European reputation,

while the Regio Ducal Teatro was at

that time one of the leading opera

houses.

But Mozart was no longer an unknown

quantity in Milan. After all, his

first opera for Milan, “Mitridate"

(for the Carnival season of 1770/71),

was quite successful. Shortly

afterwards he was accorded the

“immortal honour” (his father’s words)

by the Viennese Court of composing a

“serenata teatrale" for the marriage

of Archduke Ferdinand to Princess

Maria Ricciarda Beatrice d’Este in

October 1771. This was “Ascanio in

Alba", with a text by Giuseppe Parini

(1729-1799), one of the leading

Italian poets of the 18th century. For

some time after that the Archduke (the

Imperial Viceroy in Lombardy) seems to

have been well disposed toward Mozart.

His good connections in noble and

politically influential circles may

have assisted him in obtaining his

latest commission, although they would

not have been the decisive factor in

Mozart’s career as an operatic

composer, which had begun promisingly,

if not brilliantly, in the birthplace

of opera. He could at that time have

had no idea that “Lucio Silla" would

be his last operatic commission for

Italy. The end of Mozart’s Italian

operatic career is really rather a

mystery, particularly when one

considers how many “oltramontani"

before and after him were successful

in the field of opera in Italy and

gained an European reputation (notably

Handel, J. A. Hasse and J. C. Bach),

and that “Lucio Silla" was certainly

no failure.

The conditions which Mozart

encountered in the Regio Ducal Teatro

in Milan could hardly have been more

favourable. He had at his disposal an

excellent orchestra of some sixty

musicians, a large complement for

those days, which was widely renowned

for the precision of its ensemble

playing. First-class singers, the

castrato Venanzio Rauzzini (1746-1810)

and the soprano Anna de Amicis

Buonsolazzi (ca. 1733-1816) had been

engaged for the two principal roles,

that of the “primo uomo" (first

castrato) Cecilio and the “prima

donna", the leading female role of

Giunia. incidentally, Mozart was on

good terms, almost amounting to

friendship, with both of them. During

the time that Silla was being

performed he wrote the motet

“Exsultate, jubilate" K. 165 (158a)

for Rauzzini. The tenor originally

engaged for the title role, Arcangelo

Cortini, enjoyed a considerable

reputation. But he fell ill and had to

be replaced in great haste by Bassano

Morgnoni from Lodi, a singer whose

field of activity had been in church

and who was entirely lacking in stage

experience. Leopold, in expressing his

concern, wrote on

28th November 1772 that the tenor must

be “not only a good singer, but an

exceptionally good actor and have an

impressive personality [...], in order

to give a notable performance as Lucio

Siila.” Morgnoni may have been a good

singer, but he certainly was not a

good actor. This miscasting may have

had a detrimental effect on the opera,

because Mozart had to reduce Silla’s

arias from the four originally planned

to two, while the

“supporting” couple, Celia and Clnna

(the latter sung by a woman instead of

a second castrato) were given four and

three Arias respectively. One of the

consequences was that the musical

weight of the opera was brought into

conflict with its main theme, namely

Silla’s renunciation of power in the

cause of humane virtue. Musically the

central character was now far less

important than the plot implied, thereby

highlighting the contradiction

present in this and other similar

operas in which the eponymous

character who enjoys the highest

position and is responsible for setting

in motion the conflicts and action of

the plot, is only a minor character in

terms of the music.

Such musical and dramatic defects were

probably not regarded as being of

great importance in those days. The

impressive sets designed by the

brothers Fabrizio, Bernardino

and Giovanni Antonio Galliari,

with their European reputation, would

have seen to that.

(incidentally their designs are still

extant.)

Mozart's “Lucio Silla" is an opera

seria, a “serious” or, more

accurately, heroic opera, and

therefore belongs to a genre

which had been established since the

1720s as the principal

type of music drama under the

influence of the poet Pietro Metastasio

(1698-1782) and his countless plays,

which had been repeatedly set to music

and had revived the international

reputation of Italian music. Its

usual designation, which also

reflected its comprehensive

pretensions, was “dramma per musica".

(The more colloquial term opera seria

only came into use after about 1750,

when musical comedy began to compete

with “dramma per musica" and a general

term was needed to distinguish it from

“dramma giocoso [per musica]"

on the one hand and “opera buffa" on

the other. It is

therefore incorrect to set off the

supposedly conventional “opera seria”

against the supposedly unconventional

“dramma per musica".) When Mozart,

a mere 16-year-old, composed “Lucio

Silla", the heroic opera was already a

long established, somewhat

old-fashioned genre, and musically was

entering its last phase. The lively,

cheerful and witty musical comedy had

long since begun to under-mine the

position of “dramma per musica", and

it was no coincidence that the most

important Italian composers of Mozart’s

generation made their names in “opera

buffa". Nevertheless in

1770 the "seria" was by no means an

anachronism and still represented the

musical theatre of court ceremonial,

even though, in its traditional form,

it was no longer unchallenged; it

disseminated courtly polish and the

allegorical heroic world of a

glorified antiquity even in those

places which lacked a centre of

courtly influence, and was the

embodiment of the age of aristocracy.

Metastasio, the “poeta

Cesareo", the Imperial Court Poet in

Vienna, still enjoyed tremendous

authority.

The commissioning theatre was normally

responsible for the choice of subject,

libretto and librettist and also for

the engagement of the singers, and in

the case of the Regio Ducal Teatro

this meant the impresario.

No one knows why the choice fell on

the subject of Lucio Silla, which is

not exactly favourable towards rulers.

Certainly Mozart was not a party to

the decision. He had to set to music

the libretto with which he was

provided. Nor was there any particular

co-operation with the librettist, on

this occasion the relatively

inexperienced Giovanni de Gamerra

(1743-1803), who took up a literary

career after serving as an officer in

the Austrian army and was employed

from 1771 to 1775 as a dramatist at

the Regio Ducal Teatro. Although he

had only written a single libretto for

a “dramma per musica” ("Armida", Milan

1771), in doing so he had developed

some ideas, not precisely for the

“reform” of the seria, but certainly

under the influence of the varied

approaches and trends towards reform,

which were at that time in the air.

(These were certainly not on the lines

of Gluck’s “Reform", which actually

achieved as little “reforming” of the

seria as did the efforts of

other composers such T. Traetta und N.

Jommelli.) Gamerra was in favour of

greater involvement of choruses,

ballets and stage magic and of the

meraviglioso (the miraculous), had an

inclination to conjure up a ghostly,

sombre atmosphere and liked situations

involving death and tombs. (He was

reputed to have a personal taste for necrophilia.)

He also favoured music which gave more

opportunities for chiaroscuro (light

and dark). Gamerra, whom

contemporaries dubbed the poeta

lagrimoso as the author of

middle-class weepies ("pièces

larmoyantes"), followed some of his

precepts in the

libretto of Lucio Silla. One instance

is the darkened stage in the burial

vault, treated as the

site of a heroic cult of the dead in

Act I (“Luogo

sepolcrale molto oscuio co' monumenti

degli eroi di Roma"), in which the

chorus also plays an unusually

important role. There were also

frequent invocations of the dead and

the spirits, and tearful,

sentimental situations, the equally

unusual scene for chorus and soloists

at (hc end, and the occasional choice

of strange metres which sometimes

change in the course of

a vocal number. Otherwise Gamerra

adhered to the tradition of “dramma per

musica” after the manner of Metastasio,

which allowed rather more scope for

manoeuvre than is generally thought.

Gamerra had actually presented his

drama for approval to Metastasio

- still the highest authority where

heroic opera was concerned - and had

made great play with his approbation

in the prologue to the libretto. (We know

from Leopold Mozart’s

letters that Metastasio

made some changes, but unfortunately

these can no longer be identified.) In

fact tradition was largely observed,

both with regard to

the subject matter and its treatment.

The basis of the opera is a glorified

episode from Roman history, that is to

say, a historical subject which, as is

always the case in opera seria, serves

to present in allegorical form common

human behaviour and conflicts. A

typical element is the interweaving of

affairs of state (in this case a

conspiracy to overthrow the dictator)

with an amorous conflict, which

provides the actual plot and is

entirely fictional. It

is concerned with the presentation in

symbolic form of the upholding of

exalted virtues of constancy,

fidelity, readiness for sacrifice and

death for the sake of love (on the

part of Cecilio and Giunia) and

self-mastery (on the part of Lucio

Silla). Silla, who is a tyrant and an

example of the unlawful exercise of

power, conquers himself and his impure

passion for Giunia; he is “vincitor di

se stesso” (victor over himself),

according to the formula which is

repeated countless times in various

ways in heroic opera. It

is remarkable, albeit a matter of

chance, that the seria dramas which

Mozart set to music, from “Mitridate"

(1770) to "La

clemenza di Tito" (1791), all boil

down to a ruler`s exemplary exercise

of will-power. The “dramma per musica"

always fulfilled a didactic role; it

was, to quote Schiller, "a moral

institution", intended to speak with

the true language of the heart (the

emotions) when in conflict with

political power groupihgs and

intrigues, to remind the mighty of

their shortcomings and to hold up to

them the mirror of virtue. It

was also necessary, therefore, to have

a “lieto fine" (happy ending) to match

the function of the music in the

promotion of harmony. This was the

culmination of the symbolic, totally

unrealistic, artificial and

ceremonially stylised theatre which

the seria represented and which, after

the experiences of the 19th century,

it was difficult to appreciate fully.

The very fact that a ruler like Silla

should not only stand aside for the

lovers, but also voluntarily give up

power and restore freedom and the

republican constitution, was probably

only tolerable in the age of

absolutism because Gamerra was able to

refer to historical facts and because

Lucio Silla as a dictator did not

exercise legitimate authority.

Gamerra adhered strictly to the

hierarchical dramatis personae of

heroic opera, consisting of 6 or 7

characters: the heroic pair of lovers,

the prima donna (Giunia) and the

primo uomo (Cecilio) are opposed by

the figure of authority (primo

tenore). A second couple of less

importance are Celia (seconda donna)

and Lucio Cinna (secondo uomo, in

Milan a travesty part), close friends

of the more senior couple, but with

more complicated relationships to the

leading figures and to one another.

The character of the

lowest standing (ultima parte or

secondo tenore) is represented by

Silla’s confidant Aufidio, whose part

is deleted in this recording. The

strongly stereotyped basic

construction of the seria which, after

all, was still the theatre for

ceremonial occasions, assumed an

audience sufficiently familiar with

the rules governing the genre to be

able to appreciate any variation in

the relations between the characters,

sind ideally also the nuances in the

stylised diction. Also probability was

accorded loss importance, compared

with symbolism, than was the case in

later opera. This is not the least

important of the obstacles in the way

of a proper understanding at the

present time of the “dramma per

musica". Even more difficult, perhaps,

is a comprelionsion of the heroic

ideal which was in those days

associated with moral teaching

rlorived from subjects drawn from

antiquity and with the almost

invariably high and “unnatural”

tessitura of the castrati.

How then

did Mozart react to this genre and to

Gamerra’s drama in particular? Initially

just like any other opera composer of

his time, that is to say he tried,

without any aspiration

towards reform, which incidentally

never concerned him even in later years,

to comply with the requirements

of the genre and the demands of the

singers. This involved

taking account in the music of the

hierarchy of roles and working the emotional

and temperamental situation and

the "chiaroscuro" appropriately into

the arias, in

a word, composing absorbing and varied

music. Neither is there any indication

that he was doubtful, let alone

critical of the seria tradition,

although Gluck’s effortes were

certainly not unknown to him. He had

never been able to come to terms with

the ideas of Gluck and

Calzabigi, which involved reducing the

autonomy of the music in relation to

the developement of the plot. (He was

never further away from Gluck than in

“Idomeneo", where they

appeared to be closest). It

was not within his powers or his

intentions to remedy the undoubted

defects in the drama of Lucio Silla,

particularly the excessive length of

Acts II and III,

and a certain uniformity in the

situations. But to compensate for this

the music, particularly in the arias

and the scenes between the

protagonists Cecilio and Giunia,

acquired a new and unexpected tone,

far removed from the conventions, and

an obvious diversity exuding original

thought and direct emotion. Even the

conventional elements, which are

certainly not lacking,

appear in their context to have been

seized by a new, youthful and

overwhelming spirit and transformed

from within. The antiquated genre of

“dramma per musica" seems to have been

given a new lease of life. Nothing

goes beyond the prescribed framework,

except that the arias are much more

lengthy than was usual. The situation

is both mysterious and

fascinating: Mozart’s music for “Lucio

Silla" in no way turns its back on

traditional forms, but viewed sub

specie aeternitatis it contains the

seeds of a new beginning. A novel

flexibility in its construction and

new plasticity in the concepts allow

the character of the events to emerge,

even where Mozart is following the

conventional forms. This is matched by

an unusually intricate and varied

orchestration, which may have

irritated many of the audience at the

time, who at best would have excused

it on the ground of youthful

impetuosity derived from lack of

experience. If Metastasio, who had

always worked on the principle of not

allowing the music to get the better

of the drama, had ever heard “Lucio

Silla", he would have sharply

condemned it.

Even the sweeping concerto-like

coloratura passages which Mozart,

according to the custom of the period,

tailor-made for the protagonists, seem

to be filled with emotional content, whether

it be tender, joyful, ecstatic or

desperate. The extent to which Mozart

tried, within the limits permitted by

Gamerra's drama, to bring out the

focal points of the immanent plot

entirely in the music is shown, on the

one hand, by an unusually extensive

use of recitatives accompanied by the

orchestra (recitativo accompagnato),

and on the other hand by a tendency to

link, whenever possible, groups of

scenes together musically. In

Act I, after

Cinna’s sparkling exit aria (No.

1 “Vieni ov’amor

t’invita"), Cecilio’s solo scene

begins, without any intervening

recitativo secco with an accompagnato.

The great aria which follows, “Il

tenero momento” (No. 2),

Cecilio’s first in the opera, sweeps

aside the fearful questions of the

recitative and is

sustained by overflowing joy

of life and exultant anticipation of

the meeting with his beloved. From the

end of Scene Five onwards (Act I),

after Giunia’s passionate

argument with the tyrant Silla

and the declaration of her

determination always to despise

the dictator and remain true to her

lover, there is a great arch, broken

only by a short secco,

from Giunia`s aria "Dalla

sponda tenebrosa" (No. 4), spanning

Silla's only important aria (No.

5) with its preceding accompagnato, to

the impressive scene with the Chorus

(No. 6) and the effusive encounter of

the lovers in the duet finale of the

Act "D’Eliso in sen m'attendi” (No.

7). As early as Giunia’s aria "Dalla

sponda tenebrosa" (No.

4) a new serious, exalted tone is

perceptible, which establishes

Giunia’s impassioned, ecstatic rapport

with the spirits of her heroic

forefathers. The aura of

the other world, her devotion to the

beloved whom she believes to be dead,

and burning indignation with the

dictator stamp the aria with genuine

emotion fed by the proximity of death,

which does not draw upon customary

feelings but upon truth. Here and

in the following series of

scenes Mozart already associates the

key of E flat with the dramatic

Ombra (shades) scene customary in

opera seria (dialogue with imagined

spirits of beloved or honoured

individuals who usually are not dead

at all). But the appropriate

atmosphere is not evoked until after

the change of scene: Magnificence, gloom,

the proximity of death are the

elements of the scene. It was to this

scene in particular that Mozart

managed to impart an incomparable

sublimity, intensity and variety

of emotion: originally in Cecilio’s

wide-ranging accompagnato "Morte,

morte fatal", then

returning to the ombra key of E flat

in the great invocation Chorus (No.

6), the central

feature of which (Molto Adagio) is

provided by Giunia’s elegiac arioso

"Del padre ombra diletta”. The

unexpected appearance of Cecilio gives

rise to the duet in A,

(No. 7), rising to a climax of

blissful joy, which brings Act I

to an end. There is thus a moving

progression from tempestuous grief,

through solemn lamentation in homage

to the heroic dead (E flat) to the

more exalted “joyfulness" (A major) of

the final duet. It shows

what could have been made of the seria

if Mozart had continued in this way.

At the heart of Act II

are Cecilio’s scena

(accompagnato and Aria No.

9), Giunia’s (acc. and Aria No.

11), a further aria

for Cecilio “Ah se a morir mi chiama

(No. 14 in E flat major), which

reverts to the ombra

style, Giunia’s important solo scena

(acc. and Aria No. 16 “Parto,

m’affretto"), which expresses agony of

spirit and despair with such lack of

restraint that all the conventions of

the seria appear to be swept away. The

passionate trio which concludes Act II

(No. 18) brings the star-crossed

lovers Giunia and Cecilio

face to face with their furious

antagonist Silla.

In Act III

the lovers’ (supposed) last farewell

goes straight to the heart with the

simple but touching magic of Cecilio’s

consolatory aria “Pupille amate" (No.

21), expressed with dancelike grace

(Tempo di Menuetto),

and in the tragic pathos of Giunia`s

solo scena which immediately follows,

the C minor aria of which “Fra i

pensier più funesti di

morte" (No. 22) again resembles the

ombra style. The final Chorus, which

is exceptionally lengthy for a normal

seria, celebrates in ceremonial

rejoicing the tyrant’s change of

heart and the happy ending. Its

structure, with solo verses and a

choral refrain, suggests a performance

in dance form, which may have also

been Gamerra's original conception. It

is still an open question whether the

final number was actually danced or

whether the dance was performed

subsequently to the music of the

Chaconne, referred to in the libretto

as a Giaconna which, like the other

two ballet interludes between the

Acts, was not composed by Mozart.

(In one of the original

sources the final Chorus is designated

as Giaconna.)

The ballet interludes between the Acts

were an important element in the

performance of a seria, with the final

ballet giving special emphasis to the

ceremonial and celebratory character

of the occasion (as was later the case

with “Idomeneo”). Mozart’s

powers of imagination were, however,

particularly challenged by the

dramatic, emotional and uplifting

scenes, although he was by no means

indifferent to the music for the

less prominent roles (particularly

Celia and Cinna). The unmistakeably

novel element is the intrinsic

importance of Mozart’s

music in crucial moments, which makes

individual musical numbers so

interesting that the nicely calculated

balance brween drama and music in the

dramma per musica is destroyed. On the

one hand the concept of the seria was

well suited to the inherent spirit of

Mozart`s music and its

requirements, because it allowed

emphasis to be placed on particular

scenes and/or particular musical

numbers (e.g. arias); on the other

hand it resulted in an insurmountable

defect which called the whole genre in

question, whenever the sections which

carried the plot of the drama (the

recitatives) sank into insignificance

compared with the

musical numbers.

These things have to

be borne in mind when one seeks to

explain why nothing came of

the performance of “Lucio Silla". This

is all the more curious since the

Milan production, which was performed

26 times (26.12.1772 - 25.1.1773) was,

in spite of certain adverse

circumstances (replacement of the

tenor and some incidents at the

premiere), not a failure. Nor

was any objection taken to the

six-hour duration of the opera

with its ballet interludes.

Indeed, Gamerra’s libretto was later

set to music on several occasions,

among others by J. C. Bach in 1774.

But Mozart’s “Lucio Silla" disappeared

from the scene like the majority of

average operas of the period. The work

did not make operatic history. We

shall never know whether any of the

public of the time had any idea what

an event this music was.

Stefan Kunze

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|