|

1 CD -

2292-44633-2 - (p) 1990

|

|

| Georg Philipp

Telemann (1681-1767) |

|

|

|

| Ino - Cantata - Text: Karl

Wilhelm Ramler |

33' 25" |

33' 25" |

|

| -

Recitativo "Wohin? Wo soll ich hin?" |

0' 48" |

|

1

|

| - Aria "Ungöttliche

Saturnia" |

6' 23" |

|

2

|

| -

Recitativo "O all ihr Mächte des

Olympus" |

3' 11" |

|

3

|

| - Larghetto

"Wo bin ich?" |

4' 25" |

|

4

|

| - Vivace

con molto affetto "Ivh seh' ihn!" |

3' 11" |

|

5

|

| - Tanz der

Tritoten: Allegramente - Vivace spirituoso

e con affetto |

1' 50" |

|

6

|

| -

Recitativo "Ungewohnte Symphonien" |

1' 27" |

|

7

|

| - Aria "Meint

ihr mich, ihr Nereiden?" |

5' 19" |

|

8

|

| -

Recitativo "Und nun! Ihr wendet euch" |

2' 09" |

|

9

|

| - Aria "Tönt

in meinem Lobgesng" |

9' 22" |

|

10

|

|

|

|

|

| Georg Friedrich Händel

(1685-1759) |

|

|

|

| Apollo e Dafne - Cantata à due

con stromenti - Text: B. Panfili |

30' 34" |

30' 34" |

|

| -

Recitativo (Apollo) "La terra è

liberata" |

0' 51" |

|

11

|

- Aria

(Apollo) "Prende il ben dell'universo"

|

3' 46" |

|

12

|

-

Recitativo (Apollo) "Ch'il superbetto

amore"

|

0' 33" |

|

13

|

- Aria (Apollo) "Spezza

l'arco"

|

2' 49" |

|

14

|

| - Aria (Dafne) "Felicissima

quest'alma" |

4' 35" |

|

15

|

- Recitativo (Apollo,

Dafne) "Che voce! Che beltà!"

|

1' 09" |

|

16

|

- Aria (Dafne) "Ardi,

ardori"

|

3' 58" |

|

17

|

| - Recitativo (Apollo,

Dafne) "Che crudel! Ch'importuno" |

0' 15" |

|

18

|

| - Duetto (Dafne, Apollo)

"Una guerra ho dentro il seno" |

1' 58" |

|

19

|

| - Recitativo (Apollo) "Placati

al fin, o cara" |

0' 24" |

|

20

|

| - Aria (Apollo) "Come

rosa in su la spina" |

2' 25" |

|

21

|

- Recitativo (Dafne) "Ah,

ch'un Dio non dovrebbe"

|

0' 26" |

|

22

|

| - Aria (Dafne) "Come

in ciel benigna stella" |

3' 08" |

|

23

|

| - Recitativo (Apollo,

Dafne) "Odi la mia ragion" |

0' 32" |

|

24

|

| - Duetto (Dafne, Apollo)

"Deh, lascia addolcire" |

2' 45" |

|

25

|

| - Recitativo (Apollo,

Dafne) "Sempre t'adorerò" |

0' 23" |

|

26

|

| - Aria (Apollo) "Mie

piante correte" |

3' 01" |

|

27

|

| - Aria (Apollo) "Cara

pianta" |

3' 42" |

|

28

|

|

|

|

|

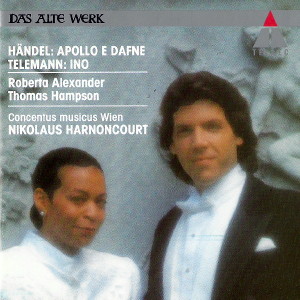

| Roberta Alexander,

Ino (Telemann), Dafne (Händel) |

|

| Thomas Hampson,

Apollo (Händel) |

|

|

|

CONCENTUS

MUSICUS WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

|

| -

Robert Wolf, Traverso (Telemann) |

-

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

|

| -

Sylvie Summereder, Traverso

(Telemann) |

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

|

| -

Kathleen Putnam, Naturhorn

(Telemann) |

-

Doris Köstemberger, Violine

|

|

| -

Alois Schlor, Naturhorn

(Telemann) |

-

Gerold Klaus, Violine |

|

| -

Hans Gangler, Oboe (Händel) |

-

Maria Kubizek, Violine |

|

| -

Paul Hailperin, Oboe (Händel) |

-

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violine |

|

| -

Albert Grazzi, Fagott (Händel) |

-

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

|

-

Erich Höbarth, Violine

|

-

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

-

Dorle Sommer, Viola |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Mark Peters, Violoncello |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo, Orgel |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria) - settembre

1988 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 2292-44633-2 - (1 cd)

- 75' 09" - (p) 1990 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

When the

22-year-old George Frederic Handel

felt the urge to leave his native

Halle - a small town

in Saxony -for the centres of the most

influential musical style of the time,

i.e. Rome, Florence, Naples

and Venice, this was without a doubt

an expression of insatiable curiosity

and the desire to broaden his horizon,

such as is typical of a genius as a

rule. Handel arrived in Italy

in 1706 or 1707, and when he returned

to Germany in 1710, he had spent three

long years literally soaking up Italian

techniques, especially in the field of

vocal writing. The four cities in

which Handel stayed, alternating

between one and the other, were at the

same time the centres of different

styles of singing. In

Florence, the birthplace of monody

and thus of opera heavy with emotion,

the principle of recitative solo

singing was followed, dramatic and

lyrical throughout and with melodies

of an arioso nature. In Rome, where

"modern" opera had been officially

banned until 1709, the opulent vocal

polyphony of the Palestrina era (i.e.

the Latin sacred oratorio) continued

to predominate. In

Naples, on the other hand, Handel

encountered a unique mixture of highly

cultivated, technically advanced

music, both sacred and profane, and

spontaneous folk music - a mixture

that produced an attractive-sounding

and artistic synthesis full of pathos.

And finally in Venice, the inquisitive

traveller became acquainted with the

glorious colour of the multiple choir

tradition as well as with instrumental

music that had developed along

virtuoso lines. These were four

different “musical

landscapes", in other words, in which

Handel spent time, learning,

imitating, reproducing and in the

final event producing in his own

right. His time in Italy was a period

of thorough study, without which the

rich harvest of operas and oratorios

that he later produced would have been

inconceivable. In these years Handel

started off “modestly", as it were, by

composing a hundred or so profane

cantatas for one or more voices,

instrumental accompaniment and

continuo as well as another twenty or

so chamber duets with accompanying

continuo: experimentation on a fairly

small scale, then, which was later to

assume greater dimensions.

The duo cantata “APOLLO E DAFNE”

probably also comes from Handel’s time

in Naples, and can be cautiously dated

to the winter of 1708/09; the text was

written by Cardinal B. Panfili, a

patron of Handel's. The

plot conforms with the custom of the

time in being edifying, didactic and

allegorical, and in being taken from

Greek mythology. The god Apollo has

just freed Greece from a great

nuisance by killing the dragon Python,

and praises the superiority of his bow

to that ot Cupid, which he says could

never injure him. At that moment he

catches sight of Daphne and falls in

love with her at once. But Daphne

rejects him, for she mistrusts the

passion of a radiant

hero passing himself off as the

brother of Diana. Apollo starts to

make advances towards her, pulling out

all the stops of the fine (and the not

so fine) art of seduction, but Daphne

only answers coolly: “I’d

rather die than lose my honour". When

it is scarcely possible to resist

Apollo’s importunate badgering any

longer, the nymph suddenly turns into

a laurel tree, and Apollo calms down

and resigns himself to the situation.

The battle between the sexes, devotion

and resistance, the contrast between

desire and purity: the moral comes in

at the appropriate place. For Handel,

these emotions that surge first one

way, then the other, serve as

keywords, so to speak, beneath which

he can spread out emotional tableaux

such as he learnt in Italy.

In a few places, the

meagre plot is pushed ahead with secco

recitatives, only to come to a halt

once more and give way to renewed

concentration on the psychological

aspects of the story. Apollo is the

character type that is depicted in

bright triads, as if trumpets were

announcing his appearance; the kind of

hero who is always pressing ahead,

very much the man of action, and full

of energy in musical terms, too.

Daphne is quite different: she is

given a delicate musical guise with a

gently swaying siciliano character

("Felicissima quest’alma",

without doubt a character portrait in

the Neapolitan style), Each new sign

of emotion is reflected by an

appropriate musical gesture. One

impatient tremolo is closely followed

by another in depiction of the

agitated Apollo, quivering with tense

excitement (“Come rosa in su la

spina"), and this same agitation

recurs in the hasty fioriture of

Daphne’s aria "Come in ciel benigna",

while the contrast between sweet

temptation (Apollo) and agitated

resistance (Daphne) is built up into

an extremely dramatic scene in the

duet "Deh! Lascia

adolcire". "Scena" is also the word

used by Handel to describe the part

where Apollo tries to seize Daphne and

she changes into a laurel tree: with

the resources of precisely written

instrumental music, Handel really does

conjure up an imaginary (musical)

stage, on which the characters'

emotions are just as clearly

represented as the actual events. - He

uses a rapid scale figure to depict

Daphne’s transformation, in the style

of film music, as it were. Elegant

vocal lines and plastically conceived

figure-work create music capable of

portraying fine nuances of feeling.

Nuances of feeling that on the one

hand - in the consistently treated da

capo aria - have time to spread out

expansively, but on the other hand are

subjected to a rapid succession of hot

and cold baths in terms of different

moods, since Handel does tighten up

and shorten these arias. Handel

assimilated the foreign “musical

landscapes" rapidly and confidently,

and with cantatas of such conciseness

he laid the foundations on which the

colossal buildings of his operas were

then erected not long after.

With Telemann’s solo cantata “Ino”

we enter a transformed musical terrain

and a new period: the era of

sentimentality, of Rococo delicacy.

Telemann does, it’s true, still have

recourse to the established pattern of

the da capo in both the opening and

the closing arias. But otherwise he

does without .the secco recitative and

lets his music hug the lines of the

epic flow. What story does the cantata

tell? lt’s the tale of Ino,

the daughter of Cadmos and the sister

of Semele. After her death she cares

for her child Dionysus, but is then

stricken with madness by Hera, and

persecuted. Ino’s

spouse Athamas kills her son Learchos.

Ino throws herself

into the sea with her second son Melicertes,

but she is saved from drowning by the

Tritons and by Neptune, and is

transformed into the goddess Leucothea

and her son is changed into the god

Palaemon. A dramatic story, made into

the libretto for Telemann's cantata by

K.W.D. Ramler. Telemann, who was

already over 80, created a fresh and

easily flowing musical scenario which

derives a plastic and graphic

character from a variety of

imitative/illustrative effects in the

music - one literally "sees" the

billowing waves, and the dance of the

Tritons is endowed with mimicry

sometimes coarse, sometimes delicate.

The modernity of such a natural

musical language (in both senses of

the word) is closely related to the

simplicity of Gluck. Indeed, one has

the impression that the reform of

opera that Gluck ushered in with his

"Alceste" has been taken at face value

here, for the rhythm and the emotional

gestures of the music Telemann wrote

in his old age harmonize perfectly

with the vocal line and with the

natural accents of the language.

Extravagant textual repeats such as

were still popular with Handel do not

occur here: the successive stages of

the narrative evolve smoothly, without

clear divisions. Where Handel still

preferred the sharp contrast between

different emotions, Telemann seems to

be more interested in gradual changes

of feeling. It is in this sense that

the many accompagnato recitatives are

to be understood,

and with such a recitative the event

in question is "sprung" on the

listener in a manner similar to the

narrative technique of a modern short

story. The grandiose Handelian pathos

as against sensitive Telemann

sentimentality; the clearly graspable

emotional state in Handel’s music as

against the flowing emotional

transformation found in Telemann.

These are clear differences between

two cantatas, the

first of which tends to be more

didactic, while the second is more

edifying in character. Or, to put it

another way: one is representative,

the other suggestive. "Musicien poète

et peintre" - thus a

description of Telemann, later

ridiculed as just a prolific composer,

in a French travel diary. In

the muted shimmer of the strings in

the aria “Meint ihr mich?", Telemann’s

poetic skill as a painter is expressed

at its most sensuous, and offers

evidence of what was understood in

1765, on the threshold of the

Enlightenment, by the “galant style”:

highly cultivated and tasteful

naturalness.

Hans-Christian

Schmidt

Translation:

Clive Williams

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|