|

1 CD -

8.43927 ZS - (p) 1988

|

|

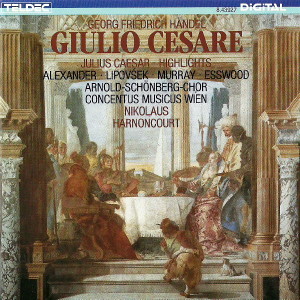

Georg

Friedrich Händel (1685-1759)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giulio Cesare

(Highlights)

|

|

|

|

| Oper in drei Akten von Nicola

Haym |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Ouverture (Grave),

Allegro |

2' 52" |

|

1 |

| - Nr. 1. Coro "Viva il

nostro Alcide" (Non troppo allegro) |

1' 51" |

|

2

|

| - Nr. 2. Aria,

Cesare "Presti ormai l'Egizia terra" (Allegro) |

2' 33" |

|

3

|

| - Nr. 4.

Aria, Cornelia "Priva son d'ogni

conforto" (Allegro) |

6' 06" |

|

4

|

| - Recitativo, Sesto

"Vani sono i lamenti" |

0' 27" |

|

5

|

| - Nr. 5. Aria,

Sesto "Svegliatevi nel core" (Allegro/Largo) |

4' 55" |

|

6

|

| - Nr. 12. Aria,

Sesto "Cara speme, questo core" (Largo) |

5' 41" |

|

7

|

| - Nr. 14. Aria, Cesare

"Va tacito e nascosto" (Andante, e

piano) |

6' 14" |

|

8

|

| - Nr. 22. Aria, Cornelia

"Cessa omai di sospirare!" (Andante) |

3' 59" |

|

9

|

| - Nr. 27. Aria,

Cleopatra "Se pietà di me non senti" (Largo) |

9' 41" |

|

10

|

| - Sinfonia bellica (Allegro) |

0' 48" |

|

11

|

| - Nr. 37. Aria,

Cleopatra "Da tempeste il legno infranto"

(Allegro) |

6' 13" |

|

12

|

| - Sinfonia. La Marche |

3' 19" |

|

13

|

| - Nr. 40. Coro e Duetto

"Ritorni ormai nel nostro core" (Bourée) |

3' 24" |

|

14

|

|

|

|

|

| Paul Esswood,

Giulio Cesare

|

|

Roberta Alexander,

Cleopatra

|

|

| Lucia Popp, Cleopatra (Nr.

40) |

|

| Marjana Lipovśek,

Cornelia |

|

| Ann Murray, Sesto |

|

|

|

| Arnold-Schönberg-Chor

/ Erwin G. Ortner, Leitung |

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe, Blockflöte |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Valerie Darke, Oboe |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Jürg Schaeftlein, Oboe |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Sem Kegley, Oboe |

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violine |

-

Leopold Stastny, Traversière, Blockflöte |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Milan Turković, Fagott |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

-

Stepan Turnovsky, Fagott |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Michael Höltzel, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Peter Matzka, Violine |

-

Elmar Eisner, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Anjuta Grabowski, Violine |

-

Alois Schlor, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Regina Schröder, Violine |

-

Matthias Ramb, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

-

Friedemann Immer, Naturtrompete

in D |

|

| -

Josef de Sordi, Viola |

-

Richard Rudolf, Naturtrompete in

D

|

|

| -

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

-

Hermann Schober, Naturtrompete in

D

|

|

| -

Rudolf Leopold, Violoncello |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo, Orgel |

|

| -

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

-

Gordon Murray, Cembalo, Orgel |

|

| -

Kurt Hammer, Pauken |

-

Edward Witsenburg, Barockharfe |

|

|

-

Theorbe, Luca Pianca |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Vienna (Austria) - aprile 1984

e maggio 1985 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 8.43927 ZS - (1

cd) - 58' 26" - (p) 1988 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

“Giulio Cesare”,

composed as a direct ’neighbour’ to

the two other masterpieces “Tamerlano”

(1724) and “Rodelinda” (1725) and

premièred on 20th

February 1724 in the King’s Theatre,

Haymarket, is not only one of the most

important of all Handel’s operas - it

also helped its creator to win his first

victory in a war so rich in both

triumphs and defeats - the London

opera war. In 1719 a group of noblemen

under the patronage of the King had

founded a joint-stock company with the

name “Royal Academy of Music”,

appointing Handel as its musical

director. The “Royal

Academy”, not to be confused with the

present-day college of the same name,

was no more nor less than an operatic

venture intended not only to entertain

wealthy noblemen, but also to make a

profit. Handel, wo had engaged firstclass

Italian singers in Düsseldorf

und Dresden for the newly-founded

company, did not remain sole musical

director for long. True to the old

trader’s motto that competition is

good for business, the shareholders

soon saw fit to appoint a second and

in due course even a third composer in

the hope of increasing the appeal of

the new opera house and thus the

box-office takings. One of these two

composers was the same Giovanni

Bononcini whose opers “Il trionfo di

Camilla” was the most frequently

performed work of a whole epoch.

“Camilla” was the first

international repertoire opera, so to

speak, and was given over a hundred

times in London alone well into the

time of the feuds. A musical rivalry

sprang up between Handel and

Bononcini, which the partisans of the

two composers were quick to expand

into a political controversy. Since

Handel enjoyed the open protection of

the King, the anti-royalist took

Bononcini’s side. Both composers wrote

one opera aner another in rapid

succession, as if they were trying to

occupy further ground with them.

Handel finally managed to vanquish his

rival from the field

for once and for all with “Giulio

Cesare”. Bonocini left the Royal

Academy, and Handel remained the sole

victor until the famous “War of the

Primadonnas” offered old enmities a

new battlefield two years later.

The uninformed listener wouldn’t know

that “Giulio Cesare” was the decisive

spear-thrust in an opera war - on the

contrary, Handel wrote here perhaps

the most erotic opera music in his

entire oeuvre, music full of deadly

serious love, full of wooing and

seduction, full of tempestuous

passion. In this opera Julius

Caesar appears not as the robust

middle-aged man of history, but as a

soldier and lover full of youthful fire.

And Handel’s musical characterization

of Cleopatra takes the wind out of the

sails of all insistent claims that the

dramatic technique of opera seria,

with its da capo arias

rich in coloratura at the end of a

scene, made psychologically convincing

character portrayal impossible. For in

the course of Handel’s opera,

Cleopatra changes from a frivolous

young beauty to a woman capable of

real love. Among the secondary roles,

Cornelia, Pompey’s widow,

is particularly fine: her tragic

earnest forms a striking contrast to

the highly virtuoso parts of thetwo

main characters.

Although the emphasis was on brilliant

display singing in the operas Handel

wrote at this time - he could command

the services of the world stars of the

period, Senesino and Cuzzoni -,

“Giulio Cesare” is not lacking in

dramatically effective plot. The

London audiences, unable to understand

Italian, would not

have accepted a serious of

incomprehensible secco recitatives and

pretty arias, “Giulio Cesare” offered

spectacle for the eye as well as the

ear: processions and battle turmoil,

attempted and successful murders on

open stage, Arcardian magicianry and

victory celebrations. The fact that

Handel’s opera was triumphant over the

facile charms of Bononcini must

certainly have had something to do

with these external features - above

all, though, with Handel’s ability to

bring theatre figures grippingly to

life with his music.

Silke

Leopold

Translation;

Clive R. Williams

----------

This

recording was made in the context of a

scenic performance of the work, and

obviously the question presented

itself whether the entire opera should

be recorded and released. We finally

decided in favour of the selection of

music offered here. Unlike Handel’s

oratorios, which can be adapted to

very different types of performance,

his operas are conceived to such an

extent around the visual element that

a complete recording would be

encumbered by far too much primarily

dramatic ballast, such as the secco

recitatives. This would of course be

no problem in the case of a well-known

work, where the listener adds his own

knowledge to what he hears on disc.

But here we felt it was

more important to present the genre

itself and the style of interpretation

we have evolved.

In Giulio Cesare Handel shows

the clash of two fundamentally

different cultures: the Egyptian and

the Roman. With considerable irony and

wit, he both uses and undermines the

old form of the opera seria in the

process. Not since the Italian operas

of Monteverdi and his contemporaries -

i.e. before the crystallisation of the

opera seria with its distinct

characters and prescribed conflicts -

had there been a hero who was at the

same time a figure of ridicule.

The Romans, the embodiment of

order, permanent victors, upholders of

morality and old Roman virtue, are

glorified and ridiculed at one and the

same time Julius

Caesar introduces himself with

the famous line from his own “De Bello

Gallico”: “I came, I saw, I conquered”

- yet Cleopatra is able to twist him

round her little finger with the art

of seduction. At the climax of the war

he falls (or jumps?) into the water

and then crawls back on to land dirty,

exhausted and lonely - “Where are my

legions?”. Is that the way for the

ruler of half the world to behave? He

doesn’t win through his own strength,

but thanks to treacherous accomplices.

Cornelia, Pompey’s widow,

emphasizes time after time that she is

of Roman birth, that she

embodies the ancient Roman virtues and

is thus to be treated with respect and

awe. But at the same time she radiates

such sex appeal that just about every

man she meets - a Roman

general, Tolomeo (the “wicked”

antagonist of Caesar and Cleopatra),

Achilla (his close friend) - falls

for her without delay.

Sextus

(Sesto), Cornelia’s adolescent son,

sees himself as a true Roman hero,

but when he appears his mother

always has him in tow, and he

eagerly repeats everything she says.

To one of the many proposals of

marriage his mother receives he

answers: “No, we are not marrying.”

The Roman soldiers react as

bawdy soldiers always do, every time

a woman appears in the camp.

The Egyptians are the

personification of the insincerity

and treachery, disorden filth and

sultry desire associated with hot

southern clirnes; yet they show

imagination and a Wealth of feeling.

Cleopatra, youthful ruler

over Egypt together with her brother

Tolomeo, tries, disguised as the girl Lydia, to ensnare

Caesar, the conqueror of her

country, so that she can eliminate

her hated brother and rule alone -

without Caesar and the Romans, of

course. In the end, though, her

plans miscarry -

she falls headlong in love with

Caesar and, faced with the jubilant

crowds of Romans and Egyptians,

enters “eternal union” with him.

Everyone on the stage, Romans and

Egyptians alike, and in the audience

knows that Caesar has a faithful

wife back home

in Rome and that his vows of loyalty

to Cleopatra are lies, so the

closing festivities are nothing if

not ironic.

The whole opera, with its ironically

treated racism, can also be seen as

a kind of travel brochure for one of

the big English oriental trading

companies: Take the boat to Egypt!

It’s a bit dirty there, and not as

cool as home, but you’ll experience

the adventure of the Eastl The

people are full of fantasy,

unpredictable... the climate

sultry... all kinds of excitement

await you! The levelheaded

northerner’s envy of the

Mediterrannean or even tropical way

of life comes to the fore.

Our recording begins with the

overture [1]. This piece, which is

intended to prepare the audience for

the turbulence and colourfulness of

the opera, is dominated by hectic

emotions. The string orchestra

receives reinforcement and

additional colouring from oboes and

bassoons. A relatively rich continuo

group (two harpsichords, lute and

organ) harmonizes and rhythmizes the

basses. The overture normally

consists of three sections: a

festive or fiery opening section, a

fugued allegro and a conclusion

similar in character to the

beginning. Here

Handel unexpectedly brings a choral

minuet [2] instead of the third

section. The victorious Caesar is

greeted by the Egyptians, horns introduce a new

colour (perhaps with Oriental

effect) into the orchestral sound,

the continuo is dominated by the

organ. In abrupt contrast, this

is.followed by Caesar’s first aria [3] -

here, as required in the original,

sung by a high male voice. The aria

is a virtuoso piece of heroic

self-congratulation: he, the

triumphant victor, deserves to be received

with palm branches and the cheers

ofthe people. In

musical terms this aria is still

part of the overture, which thus

enjoys an unconventionally fiery

conclusion.

Cornelia’s sad, desolate aria [4] -

her husband Pompey has been murdered

by the Egyptians - is accompanied by

the string orchestra, organ and lute

as well as a solo flute. - By his father’s

grave, Sesto swears to revenge his

murder: The two parts of his aria

offer an extreme contrast with one

another: in the fast revenge section

he “stokes up” his own courage, as

it were, while the slow section is

composed in the manner of the

“ombra” arias traditional at the

time - accompanied

by ghostly recorders he recalls the

memory of his dead father [6]. -

Sesto’s aria that follows [7] from a

later scene, is an exeptionally

tender piece, accompanied only by a

harpsichord in soft register and a

cello. Sweet hope begins to bud, and

the listener could well think it is

the song of a young lover - but it is the hope

of finding the hated murderer and

killing him. There is bitter irony

of great dramatic effect in this

reversal of feelings and their

traditional musical expression. - Caesar and his

adversary Tolomeo face one another:

each tries to set a trap for the

other, while speaking to him in

tones of honeyed friendliness.

Caesar’s great aria [8] with the

solo horn accompaniment depicts this

situation: a huntsman creeps up on

tiptoe to outwit the game.

This nocturnal piece is a rare example

of a large natural horn solo in the piano,

hence the quiet continuo: organ and

harpsichord with peau de buffle.

- For Cornelia an end to her plight

seems to be in sight; her sigh aria

[9] with strings, organ, lute and

recorder says the exact opposite of

its musical content: there will be an

end to her sighing and lament. It is a

rhetorical game in which the pauses

play a major role as a particularly

effective “figure”.

Cleopatra’s long F

sharp minor aria [10] can be

considered the musical nucleus of the

opera: it is a grandiose lament for

the fate of her lover. Here, all

doubts as to this clever

woman’s honesty are dispelled; here

she is nothing but a woman in love.

The Baroque harp is the special

continuo instrument for Cleopatra,

combined here with the organ.

The war music [11], in which as so

often in the Baroque period the sound

of trumpets is imitated by string and

oboes, signals the Roman victory -

Cleopatra reacts to the news of

Caesar’s rescue and the destruction of

Tolomeo and Achilla with a song of

triumph [12]: this piece, like the

great aria of mourning, shows that the

part of the Egyptian queen is written

for a primadonna assoluta. It

contains the greatest expressive

range, from legatissimo through to

coloratura, and the scale encompassed

stretches from a deep mezzo to high

soprano. - The

arade that leads to the closing

tableau is ushered in by two

instrumental pieces [13]: a

complex one with two subtly set groups

of horns (right and left), and a

simple, brilliant march with timpani

and trumpets. The contrast of “Egyptian”

and “Roman” is obviously intended to

be repeated once more here. - The

final chorus [14] with the duet

between Caesar and Cleopatra in the

central section is a bourée. The

entire opera is thus framed by two

choral dances: a strictly formal

framework for the most luxuriant

subject-matter. Within

the bourée itself we find a similar

structure: the two outer sections form

a fairly strict, festive frame for a

very soft central part whose

sensuality seems genuine, but whose

text - vows of eternal loyalty

- seems ironic in the extreme.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Translations: Clive R. Williams

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|