|

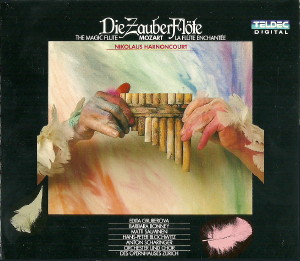

2 LP -

6.35766 EX - (p) 1988

|

|

| 2 CD -

8.35766 ZA - (p) 1988 |

|

Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Die Zauberflöte, KV 620 |

|

|

|

| Eine Große Oper in zwei Akten -

Dichtung von Emanuel Schikaneder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouverture |

|

6' 26" |

A1 |

| Erster Aufzug |

|

59' 39" |

|

| - No. 1 - Introduction: "Zu

Hilfe! zu Hilfe! sonst bin ich verloren" -

(Drei Damen, Tamino) |

6' 34" |

|

A2 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 30" |

|

A3 |

| - No. 2 - Aria: "Der Vogelfänger

bin ich ja" - (Papageno) |

3' 00" |

|

A4 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 58" |

|

A5 |

| - No. 3 - Aria: "Dies Bildnis

ist bezaubernd schön" - (Tamino) |

4' 02" |

|

A6 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 25" |

|

A7 |

| - No. 4 - Recitativo ed Aria: "O

Zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn" - (Königin

der Nacht) |

4' 36" |

|

A8 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 07" |

|

A9 |

| - No. 5 - Quintetto: "Hm! hm!

hm!" - (Drei Damen, Tamino, Papageno) |

6' 36" |

|

A10 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 22" |

|

A11 |

| - No. 6 - Terzetto: "Du feines

Täubchen" - (Pamina, Monostatos, Papageno) |

1' 36" |

|

A12 |

| - Zwischentext |

1' 07" |

|

A13 |

| - No. 7 - Duetto: "Bei Männern,

welche Liebe fühlen" - (Pamina, Papageno) |

4' 20" |

|

B1 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 07" |

|

B2 |

| - No. 8 - Finale: "Zum Ziele

führt dich diese Bahn" - (Pamina, Drei

Knaben, Tamino, Monostatos, Sarastro,

Sprecher, Papageno, Chor) |

24' 48" |

|

B3 |

| Zweiter Aufzug |

|

77' 38" |

|

| - No. 9 - Marcia |

2' 52" |

|

B4 |

| - Zwischentext |

1' 27" |

|

B5 |

| - No. 10 - Aria con Coro: "O

Isis und Osiris" - (Sarastro, Chor) |

2' 53" |

|

B6 |

| - Zwischentext |

1' 27" |

|

C1 |

| - No. 11 - Duetto: "Bewahret

euch vor Weibertücken" - (Zweiter

Priester, Sprecher) |

0' 55" |

|

C2 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 19" |

|

C3 |

| - No. 12 - Quintetto: "Wie? wie?

wie? ihr an diesem Schreckensort?" - (Drei

Damen, Tamino, Papageno) |

3' 09" |

|

C4 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 41" |

|

C5 |

| - No. 13 - Aria: "Alles fühlt

der Liebe Freuden" - (Monostatos) |

1' 14" |

|

C6 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 45" |

|

C7 |

| - No. 14 - Aria: "Der Hölle

Rache kocht in meinem Herzen" - (Königin

der Nacht) |

3' 00" |

|

C8 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 40" |

|

C9 |

| - No. 15 - Aria: "In diesen

heil'gen Hallen kennt man die Rache

nicht!" - (Sarastro) |

4' 03" |

|

C10 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 55" |

|

C11 |

| - No. 16 - Terzetto: "Seid uns

zum zweiten Mal willkommen" - (Drei

Knaben) |

1' 24" |

|

C12 |

| - Zwischentext |

1' 09" |

|

C13 |

| - No. 17 - Aria: "Ach Ich

fühl's, es ist verschwunden!" - (Pamina) |

4' 02" |

|

C14 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 37" |

|

C15 |

| - No. 18 - Chor der Priester: "O

Isis, und Osiris, welche Wonne!" |

2' 57" |

|

C16 |

| - Zwischentext |

0' 32" |

|

C17 |

| - No. 19 - Terzetto: "Soll ich

dich Teuer nicht mehr sehn?" - (Pamina,

Tamino, Sarastro) |

3' 41" |

|

C18 |

| - Zwischentext |

1' 11" |

|

C19 |

| - No. 20 - Aria: "Ein Mädchen

oder Weibchen Wünscht Papageno sich!" -

(Papageno) |

1' 35" |

|

D1 |

| - Zwischentext |

1' 03" |

|

D2 |

| - No. 21 - Finale: "Bald prangt,

den Morgen zu verkünden": |

31' 45" |

|

D3 |

| (Königin der Nacht, Pamina,

Papagena, Drei Knaben, Drei Damen, Tamino,

Monostatos, Erster und zweiter

geharnischter Mann, Sarastro, Papageno,

Chor) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Matti

Salminen, Sarastro |

Anton

Scharinger, Papageno |

|

| Hans-Peter

Blockwitz, Tamino |

Edith

Schmid, Papagena |

|

Thomas

Hampson, Sprecher

|

Peter

Keller, Monostatos |

|

Alexander

Maly, Erster Priester

|

Stefan

Gienger, Knabe |

|

| Waldemar

Kmentt, Zweiter Priester |

Markus

Baur, Knabe |

|

| Edita

Gruberova, Königin der

Nacht |

Andreas

Fischer, Knabe |

|

| Barbara

Bonney, Pamina |

Thomas

Moser, Erster Gehamischter |

|

| Pamela

Coburn, Erste Dame |

Antti

Suhonen, Zweiter

Gehamischter |

|

| Delores

Ziegler, Zweiter Dame |

Gertraud

Jesserer, Zwischentext |

|

| Marjana

Lipovšek, Dritte Dame |

|

|

|

|

| Chor des Opernhauses Zürich

/ Erich Widl, Einstudierung |

|

| Orchester des Opernhauses

Zürich |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Kirche

Altstetten, Zurigo

(Svizzera) - novembre 1987 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

Wolfgang Mohr / Michael

Brammann

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 8.35766 ZA - (2 cd) -

73' 17" + 70' 26" - (p) 1988 - DDD

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Teldec - 6.35766 EX - (2 lp) -

73' 17" + 70' 26" - (p) 1988 - Digital

|

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt: A Family Drama

|

In the

Magic Flute there is a celebrated

“break” at the point where -

apparently without warning - the

“good” Queen of the Night suddenly

becomes "evil", where the “evil”

Sarastro becomes “good", and where the

three boys change sides; they were,

after all, provided by the Queen as

guides for the two wanderers - now we

suddenly find them in Sarastro’s camp,

giving warnings and advice. The

literature on Mozart has

for nearly 200 years been

providing innumerable explanations for

this “break". It is

suggested that the radical

reconstruction of the plot occured in

the middle of the composition of the

work because another magic opera on a

similar subiect had just appeared, or

in order to lay stress on the rites

and ideals of Freemasonry etc. All

these hypotheses are based on the

assumption that such a break exists. My

view, however, is that there is no

reason to assume - particularly with

such fairy-tale material - that such a

mistake was made. To alter the concept

without reconstructing the part which

had already been written would really

have been an incomprehensible mistake,

although in a Viennese work of this

type one cannot expect strict

consistency or realistic logic.

I am reminded of the

time when friends of ours were getting

a divorce: During the morning the

husband visited us and explained

everything from his standpoint; we

understood his point of view and were

ready to condemn his wife as his

antagonist. In

the afternoon we were visited by the

wife and we succumbed also to her

arguments: now we considered the guilt

to be his alone, he was at fault. That

is exactly what happens to Tamino in

the Magic Flute.

One can imagine the background to the

story as being that of a mighty,

mysterious family with strange castles

and fortresses, ruling with a great

following and retinue both day and

night and a whole fairytale world.

Sarastro may well have been an

interesting friend of the family with

his own power base in the exclusive

men's club of 'initiates' and with

eccentric hobbies, such as going out

hunting every day in a chariot drawn

by lions or, when the fancy took him,

turning himself into an animal. His

later contempt for women may have been

attributable to the fact that he was

attracted to the lady of the house -

the Queen of the Night - or perhaps

that she was attracted to him;

whatever the circumstances, the

’affair’ ended in hatred and jealousy.

On the death of the old 'King’ his

dominions were broken up, the Queen

inheriting everything

except power over the clay, the

‘all-consuming’ orb of the sun. The

old man had left this lo Sarastro, the

friend of the family, who may well

also have had an eye on their little daughter

Pamina, as was to

appear later on. - The property, the

entourage, (the boys, the ladies the

slaves lions etc.) and the fortresses

were all divided up more or less

clearly ,but in such a way that an

exchange, a transfer of allegiance to

the other camp, was possible without too

much trouble. The

original

community of interest is still clearly

apparent on each side. -

In the end Sarastro abducted Pamina,

ostensibly to remove her from the evil

influence of her mother, but the fact

that he was in love with her is likely

also have played its part.

Tamino bursts in upon this domestic

drama and since he first hears the

story from the lips of the Queen, he

initially becomes her dedicated

supporter and an opponent of Sarastro.

But when he enters his territory and

there hears the arguments of the other

party, he allows himself to be

persuaded of their validity and to be

’converted’. The widely quoted break

is, therefore,

nothing other than the subtle

protrayal of a common human pattern of

thought and behaviour.

Neither of the two groups emerges

morally blameless from the affair.

Just as in human relationships love

very easily turns to hate, so it is

here: the Queen has a mortal hatred

for Sarastro and his

adherents, and she has certainly been

badly treated. - Although Sarastro

surrouds himself with an aura of love

and wisdom, in his domain there are

slaves, fetters, punishment and a

truly rnurderous lecher. The fate of

his prisoners is terrible; they are 'impaled

or hanged'; 'their deaths would

involve appalling torture’; the

ordeals are said to be so severe that

not every aspirant survives them.

Threats of these dangers are quite

cynically employed. Pamina is told to

bid her beloved 'a last farewell'.

Sarastro is, therefore, by no means so

virtuous and devoted to truth:

although he solemnly sings of his love

for humanity and abjures

all thought of revenge, he has

Monostatos flogged and destroys the

Queen of the Night and her followers.

Indeed, he obviously

lies on one occasion, when he says

'that is the reason why I took her (Pamina)

by force from her proud mother’,

implying that he did it in order to

bring her and Tamino together - in

fact he abducted Pamina because he

wanted her for himself. 'I do not wish

to force love upon you... you greatly

love another'.

Neither does Sarastro's intense

passion for hunting fit in very well

with the picture of the sage who

lovingly protects all forms of life. -

The only representative of perfection

in this fairy-tale,

in which women are so reviled, is the

girl Pamina.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|