|

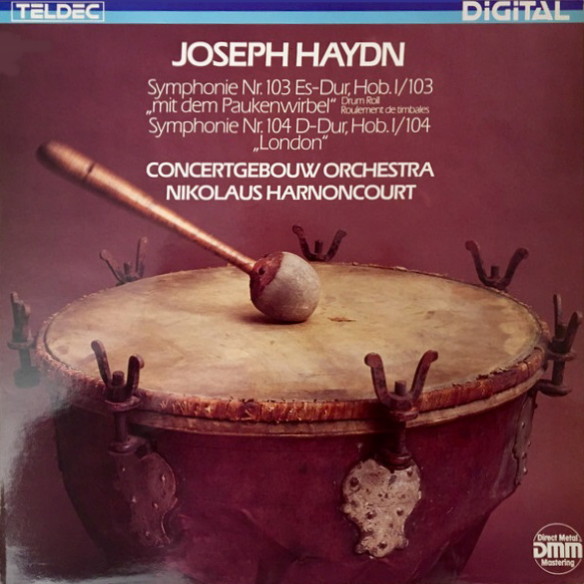

1 LP -

6.43752 AZ - (p) 1987

|

|

| 1 CD -

8.43752 ZK - (p) 1987 |

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie Nr. 103 Es-dur,

Hob. I/103 "mit dem Paukenwirbl"

|

|

30' 46" |

|

| - Adagio - Allegro con

spirito |

10' 04" |

|

A1 |

- Andante

più tosto Allegretto

|

9' 45" |

|

A2 |

- Menuett

|

5' 12" |

|

A3 |

| - Finale: Allegro con

spirito |

5' 45" |

|

A4 |

Symphonie

Nr. 104 D-dur, Hob. I/104 "London"

|

|

26' 59" |

|

- Adagio - Allegro

|

9' 14" |

|

B1 |

| - Andante |

7' 21" |

|

B2 |

| - Menuetto: Allegro - Trio |

3' 38" |

|

B3 |

- Finale spiritoso

|

6' 46" |

|

B4 |

|

|

|

|

| CONCERTGEBOUW ORCHESTRA,

AMSTERDAM |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Großer

Saal, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda)

- giugno 1987 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut A. Mühle

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 8.43752 ZK - (1 cd) - 58' 15" - (p)

1987 - DDD |

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Teldec - 6.43752

AZ - (1 lp) - 58'

15"

- (p) 1987

- Digital

|

|

|

Notes

|

“This wonderful man

never disappoints us.

Every idea of his inventive and

passionate spirit was executed by the

orchestra with rare precision and

received by the audience with equal

delight.” Thus the reviewer of the

“Morning Chronicle” on 15th April

1795, reporting on the appearance of

probably the most famous composer of

the time, whose own diary entry

shortly after this last of his London

benefit concerts read: “I made four

thousand florins this evening. That`s

only possible in England.” It

was certainly possible for Haydn, at

any rate. During his two visits to

England, 1791-92 and 1794-95, he found

ideal conditions for his music, and he

was able to adapt to them and exploit

them to his, advantage - with huge

success.

London at the end of the 18th century

was indisputably the musical capital

of Europe, after Parisian music life

had collapsed in the wake of the

French Revolution. Music publishing

and instrument building were

flourishing in London, and above all

there was already an unusually well

developed and diverse musical life -

public, open to everyone and governed

by the rules of a free market. The

audiences that poured into the city’s

rnain concert halls came as a result

from all strata of society, such as

was not the case elsewhere. The

composer who wanted to thrive in

London had to take this point into

consideration, alongside the immediate

performing conditions such as the

composition of the orchestra and the

size of the concert hall.

Haydn, who was a tireless experimenter

- the cliché ofthe fusty old “Papa

Haydn” is far from the truth -

doubtless saw these circumstances as

an appealing challenge. And in his

London Symphonies he did indeed reach

the climax of a development he had

begun shortly before in the Paris

Symphonies: the development of a

symphonic style that would appeal to

“connoisseurs” and the general

music-lover alike, that would be

popular without relinquishing even a

fraction of its artistic

sophistication.

To achieve this aim in his penultimate

symphony, no. 103, he made use of a

special resource - he

borrowed from folk music. This work

(like no. 104, it was first

performed in the “Opera Concerts” in

the King’s Theatre in the spring of

1795) simply abounds with Croatian and

Hungarian folk melodies from regions

close to the Esterhazy court where

Haydn worked for some 30 years. It is

interesting to see how Haydn does not

just quote folk tunes: he integrates

them into his own style.

The dance-like first subject of

the first movement,

for instance, takes it justification

from the context, as it were (the same

is true of the second subject): Haydn

derives it from the motifs of the slow

introduction that opens with a solo

drum roll - a feature that attracted

the greatest attention at the work’s

premiere, and of course gave the

symphony its nickname. It

becomes clear that this introduction

is in fact the true centre of the

whole movement when it reappears in

the course of the Allegro, if not

before.

The integration and stylization of

folk music also play an important role

in the other movements. The Andante is

a subtly scored set of variations on

two closely related themes that

clearly belong to the realm of folk

music. In the minuet,

the boisterous yodelling figures

are stylized by the strings. And in

the finale, Haydn derives a second

subject, a Croatian folk tune, from

the main subject.

Haydn blends the quotations so

perfectly with his own style that it

is no surprise when he does without

them for the most part in his last

symphony, no. 104. The “folk sound"

here, with the exception of the

Croatian melody in the ponderous

finale, is of Haydn`s own creation,

and is united with the utmost skill.

The cheerful theme on which the entire

first movement is based is thus

subjected to treatment that is almost

excessive. And the rather simpler idea

of the Andante gives scarcely any hint

of the distant regions of passion and

danger to which it will he taken in

the course of the movement. What did

the American musicologist Charles

Rosen say? - “The more popular Haydn’s

music became, the more academic was

his style.”

Norbert

Meurs

Translation: Clive Williams

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|