|

1 LP -

6.43187 AZ - (p) 1985

|

|

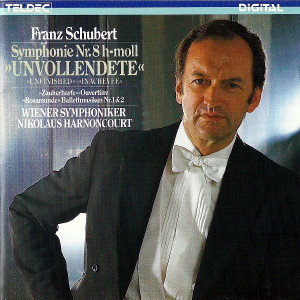

| 1 CD -

8.43187 ZK - (p) 1985 |

|

| Franz Schubert

(1797-1828) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie Nr. 8 h-moll, D 759

"Die Unvollendete" |

|

27' 44" |

|

| - Allegro

moderato |

15' 56" |

|

A1 |

| - Andante

con moto |

11' 48" |

|

A2 |

| Ouvertüre zum Zauberspiel

"Die Zauberharfe", D 644 |

|

|

|

- Andante - Allegro vivace

|

|

10' 59" |

B1 |

|

|

|

|

| Rosamunde, Fürstin von

Zypern, D 797 |

|

16' 08" |

|

| - Ballettmusik Nr. 1 - (Allegro

molto moderato - Andante un poco assai) |

8' 30" |

|

B2 |

| - Ballettmusik Nr. 2 -

(Andantino) |

7' 38" |

|

B3 |

|

|

|

|

| Wiener

Symphoniker |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Musikverein,

Vienna (Austria) - dicembre 1984

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 8.43187 ZK - (1 cd) - 55' 26" - (p)

1985 - DDD |

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Teldec - 6.43187

AZ - (1 lp) - 55'

26"

- (p) 1985 - Digital

|

|

| The

"Unfinisched" Symphony |

Remarkably,

the fact is almost unknown that Haydn,

Mozart and Beethoven, the chief

exponents of the so-called Viennese

Classical School, used literary models

as a source of inspiration. Not that

they had any intention of conveying the

subject matter of the “models” to the

listener in the way that programme music

does; on the contrary, the link with

particular models was rarely mentioned.

Important though the narrative may have

been as a source of inspiration, the

listener was not supposed to find out

about it. Even though contemporary music

lovers must surely have been aware of

such cross connections between music and

literature, the actual provenance of a

specific work was clearly of no

importance. Today’s musician and music

lover, having to leam from scratch to

appreciate the musical language of the

past, may derive much interest and

valuable assistance from an awareness of

these interrelations.

By the end of the 18th century this link

between music and literature was already

a long-established tradition and seems

to have been taken for granted. There

are several references to the use of

literary sources, and occasionally a

composer would be asked to make up a

story to fit his composition. For all

that this methods was unhesitatingly

used, it was considered something of a

trade secret, something known among

composers which, though sometimes

mentioned in theoretical works, was

never to be acknowledged in public.

Tartini, for example, noted the models

for his violin concertos on the scores

in a kind of code. Haydh told his

biographer Carpani that he made a point

of making up a story before writing a

symphony (or sonata); as an example he

quoted the well-known “America

Symphony”. Beethoven at one time

intended to indicate the literary models

of his piano sonatas by giving titles to

the various movements, but in the end he

abandoned the idea. In the thirties

Arnold Schering researched these

connections in depth. He also discovered

the link between Schubert’s allegorical

tale “My Dream” and his “Unfinished

Symphony”. I basically follow his

description.

In this narrative the 26-year old

composer unburdended himself of a

youthful experience which evidently made

a deep and lasting impression upon him.

When he was about 15 years old his

father repeatedly forbade him to

compose; when this was to no avail, he

drove him away (Schubert was a boarder

at the Imperial Choir School), so that

he was deprived of a last opportunity of

seeing his beloved mother, who fell ill

and died during his banishment. It was

only at the graveside that he was

reconciled with his father and

readmitted to the parental home. Ten

years later he recorded this event in

the form of an allegorical dream:

My Dream (3rd July 1822)

I was a brother of many brothers and

sisters. Our father and our mother were

good people. I was deeply devoted to

them all. - Once my father led us to a

feast. This made my brothers very merry.

But I was sad. Then my father approached

me and commanded me to enjoy the

delicious food. But I could not do so,

whereupon my father, becoming angry,

banished me from his sight. I tumed my

footsteps and, my heart full of infinite

love for those who scorned it, I

wandered into distant lands. For many

years I felt immense grief and immense

love tear me apart. Then I received news

of my mother’s death. I hastened to see

her, and my father, mellowed by sorrow,

did not prevent me entering. I beheld

her corpse. Tears flowed from my eyes. I

saw her lying there like the dear old

past according to which, in the

deceased’s opinion, we ought to conduct

ourselves.

And we followed her corpse in sorrow,

and the coffin sank to earth. - From

then on I stayed at home again. Then my

father led me once more to his favourite

garden. He asked me whether I liked it.

But the garden was quite repellent to

me, yet I dared not say so. Then,

becoming incensed, he asked me for the

second time: Did I like it? I denied,

trembling. At that my father struck rne

and I fled. And I turned away for the

second time and, my heart full of

infinite love for those who scorned it,

I wandered again into distant lands. I

sang my songs for many a long year. If I

attempted to sing of love, it turned to

grief. Yet if I wanted to sing of grief

alone, it turned to love.

Thus love and grief tore me apart.

One day I had news of a gentle maiden

who had recently died. A circle formed

round her gravestone in which many

youths and old men walked as though in

everlasting bliss. They spoke softly,

lest they wake the maiden.

The maiden’s gravestone seemed to send

forth heavenly thoughts like fine sparks

upon the youth, producing a gentle

sound. I longed sorely to join them. But

they told me that only a miracle

admitted to this circle. But I went to

the gravestone with slow steps and

lowered gaze, full of devotion and firm

belief, and sooner than I knew I was

within the circle, from which issued

awondrous sound; and I felt eternal

bliss gathered up into a single moment.

I also saw my father, reconciled and

loving. He took me in his arms and wept.

But I wept even more.

Franz Schubert

Shortly afterwards, on 30th October

1822, Schubert embarked on the fair copy

of the symphony. Assuming than an

appropriate time had been spent on the

work, sketching and drafting, the

narrative and the symphony are

chronologically close to one another.

The narrative consists of two parts: (1)

The two incidents with his father and

the death of his mother. (2) Comfort and

transnguration in the realms of the

supernatural. The two movements of the

symphony correspond to the parts of the

narrative.

The first part is,as it were, structured

in literary sonata form. The first

conflict with his father and his

banishment correspond to the exposition

of the allegro moderato; his mother’s

death and the scene at the graveside

correspond to the development section;

the second conflict with his father

(which is not mentioned in Schubert’s

biography) corresponds to the

recapitulation. Even the structure is

full of parallels:

1st part

(Once my father led us to a feast)

...But I could not do so, whereupon my

father, becoming angry, banished me from

his sight.

I turned my footsteps and, my heart full

of infinite love for those who scorned

it, I wandered into distant lands.

For many years I felt immense grief and

immense love tear me apart.

2nd part

(Then my father led me once more to his

favourite garden) ..."Then, becoming

incensed, ...I denied, trembling. At

that my father struck and I fled.

And I turned away for the second time

and, my heart full of infinite love for

those who scorned it, I wandered again

into distant lands.

Thus love and grief tore me apart.

The

introduction and the two “triggers” - first the

delicious food and then the

favourite

garden, which serve as symbols that

justify his father’s severity - do not

occur in the symphony.

This symphony is not unhnished. Like the

dream narrative, it comes to a close

with a “celestial vision”. - It is true

that Schubert tried to carry matters

further in the music with a passionately

excited scherzo. He abandoned the

attempt, no doubt because he realised

that it was pointless; the work was

complete, finished in both senses of the

word. Schubert must have come to this

conclusion, otherwise he would, in the

years that followed, have completed the

symphony, this unique work of genius. He

himself described the two movements,

without further comment, as a

“symphony”; it was not unfinished, but

deliberately left in two-movement form.

(...)

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

Translation:

Lindsay Craig

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|