|

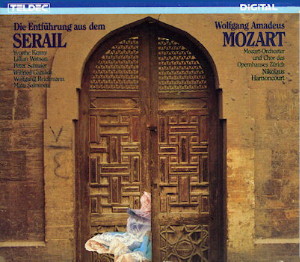

3 LP -

6.35673 GK - (p) 1985

|

|

| 3 CD -

8.35673 ZB - (p) 1985 |

|

Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Die Entführung aus dem

Serail, KV 384 |

|

|

|

| Singspiel in drei Aufzügen, Text

nach Christoph Bretzner, frei bearbeitet

von Gottlieb Stephanie d.J. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouverture |

|

4' 12" |

A1 |

| Erster Aufzug |

|

39' 39" |

|

| - Scene 1 - No. 1 Aria: "Hier

soll ich dich denn sehen, Konstanze!" -

(Belmonte) |

2' 49" |

|

A2 |

| - Scene 1 - Dialog: "Aber wie

soll ich in den Palast kommen" -

(Belmonte) |

0' 06" |

|

A3 |

| - Scene 2 - No. 2 Lied und

Duett: "Wer ein Liebchen hat gefunden

(Osmin) - Verwünscht seist du samt deinem

Liede! (Belmonte, Osmin) |

7' 07" |

|

A4 |

| - Scene 3 - Dialog: "Könnt' ich

mir doch noch so einen Schurken auf die

Nase setyen - (Osmin, Pedrillo) |

0' 33" |

|

A5 |

| - Scene 3 - No. 3 Aria: "Solche

hergelauf ne Laffen - (Osmin) |

5' 33" |

|

A6 |

| - Scene 4 - Dialog: "Geh nur,

verwünschter Aufpasser - (Pedrillo,

Belmonte) |

1' 04" |

|

A7 |

| - Scene 5 - No. 4 Recitativo ed

Aria: "Konstanze! dich wieder zu sehen!" -

"O wie ängstlich, o wie feurig klopft mein

liebevolles Herz!" - (Belmonte) |

5' 16" |

|

B1 |

| - Scene 5 - Dialog: "Geschwind,

geschwind auf die Seite und versteckt!" -

(Pedrillo) |

6' 06" |

|

B2 |

| - Scene 6 - No,. 5b Chor der

Janitscharen: "Singt dem großen Bassa

Lieder" - (Chor und Soli: Sopran, Alt,

Tenor, Baß) |

1' 43" |

|

B3 |

| - Scene 7 - Dialog: "Immer noch

traurig, geliebte Konstanze?" - (Selim,

Konstanze) |

1' 07" |

|

B4 |

| - Scene 7 - No. 6 Aria: "Ach ich

liebte, war so glücklich!" - (Konstanze) |

5' 44" |

|

|

B5 |

| - Scene 7 - Dialog: "Ach, ich

sagt' es wohl, du würdest mich hassen" -

(Konstanze, Selim) |

|

|

| - Scene 8 - Dialog: "Ihr

Schmerz, ihre Tränen, ihre Standhaftigkeit

bezaubern mein Herz immer mehr" - (Selim,

Pedrillo, Belmonte) |

1' 16" |

|

|

B6 |

| - Scene 9 - Dialog: "Ha,

Triumph, Triumph, Herr!" - (Pedrillo,

Belmonte) |

|

|

| - Scene 10 - Dialog: "Wohin? -

Hinein! - Was will das Gesicht?" - (Osmin,

Pedrillo, Belmonte) |

|

|

| - Scene 10 - No. 7 Terzett:

"Marsch, marsch, marsch! trollt euch

fort!" - (Belmonte, Pedrillo, Osmin) |

2' 15" |

|

B7... |

| Zweiter Aufzug |

|

62' 01" |

|

| - Scene 1 - Dialog: "O des

Zankens, Befehlens und Murrens wird auch

kein Ende!" - (Blonde) |

|

|

...B7 |

| - Scene 1 - No. 8 Aria: "Durch

Zärtlichkeit und Schmeicheln" - (Blonde) |

4' 41" |

|

B8 |

| - Scene 1 - Dialog: "Ei seht

doch mal, was das Mädchen vorschreiben

kann!" - (Osmin, Blonde) |

0' 51" |

|

B9 |

| - Scene 1 - No. 9 Duetto: "Ich

gehe, doch rate ich dir" - (Blonde, Osmin) |

3' 47" |

|

B10 |

| - Scene 2 - Dialog: "Wie traurig

das gute Mädchen daher kommt!" - (Blonde) |

0' 12" |

|

C1 |

| - Scene 2 - No. 10 Recitativo ed

Aria: "Welcher Wechsel herrscht in meiner

Seele" - "Traurigkeit ward mir zum Lose" -

(Konstanze) |

9' 36" |

|

C2 |

| - Scene 2 - Dialog: "Ach mein

bestes Fräulein!" - (Blonde, Konstanze) |

1' 05" |

|

|

C3 |

| - Scene 3 - Dialog: "Nun,

Konstanze, denkst du meinem Begehren

nach?" - (Selim, Konstanze) |

|

|

| - Scene 3 - No. 11 Aria:

"Martern aller Art" - (Konstanze) |

10' 25" |

|

C4 |

| - Scene 4 - Dialog: "Ist das ein

Traum?" - (Selim) |

0' 43" |

|

C5 |

| - Scene 5 - Dialog: "Kein Bassa,

keine Konstanze mehr da?" - (Blonde) |

0' 48" |

|

|

D1 |

| - Scene 6 - Dialog: "Bst, bst!

Blondchen! Ist der Weg rein?" - (Pedrillo,

Blonde) |

|

|

| - Scene 6 - No. 12 Aria: "Welche

Wonne, welche Lust" - (Blonde) |

3' 18" |

|

D2 |

| - Scene 7 - Dialog: "Ah, daß es

schon vorbei wäre!" - (Pedrillo) |

0' 19" |

|

D3 |

| - Scene 7 - No. 13 Aria: "Frisch

zum Kampfe! Frisch zum Streite!" -

(Pedrillo) |

3' 23" |

|

D4 |

| - Scene 8 - Dialog: "Ha! Geht's

hier so lustig zu?" - (Osmin, Pedrillo) |

0' 52" |

|

D5 |

| - Scene 8 - No. 14 Duetto:

"Vivat Bacchus! Bacchus lebe!" -

(Pedrillo, Osmin) |

2' 16" |

|

D6 |

| - Scene 8 - Dialog: "Wahrhaftig,

das muß ich gestehen, es geht doch nichts

über den Wein!" - (Pedrillo, Osmin) |

1' 03" |

|

|

D7 |

| - Scene 9 - Dialog: "Hute Nacht

- Brüderchen - gute Nacht!" - (Pedrillo,

Belmonte, Konstanze) |

|

|

| - Scene 9 - No. 15 Aria: "Wenn

der Freude Tränen fließen" - (Belmonte) |

7' 35" |

|

D8 |

| - Scene 9 - Dialog: "Ich hab'

hier ein Shiff in Bereitschaft" -

(Belmonte, Konstanze, Pedrillo, Blonde) |

0' 10" |

|

E1 |

| - Scene 9 - No. 16 Quartetto:

"Ach Belmonte! ach mein Leben!" -

(Konstanze, Blonde, Belmonte, Pedrillo) |

10' 57" |

|

E2... |

| Dritter Aufzug |

|

33' 33" |

|

| - Scene 1 - Dialog: "Hier,

lieber Klaas, hier leg sie indes nur

nieder" - (Pedrillo, Klaas) |

|

|

...E2 |

| - Scene 2 - Dialog: "Ach! - Ich

muß Atem holen" - (Pedrillo, Belmonte) |

|

|

...E2 |

| - Scene 3 - Dialog: "O

Konstanze, Konstanze! Wie schlägt mir das

Herz!" - (Belmonte) |

0' 12" |

|

E3 |

| - Scene 3 - No. 17 Aria: "Ich

baue ganz auf deine Stärke, vertrau', o

Liebe! deiner Macht!" - (Belmonte) |

6' 20" |

|

E4 |

| - Scene 4 - Dialog: "Alles liegt

auf dem Ohr, es ist alles so ruhig" -

(Pedrillo, Belmonte) |

0' 20" |

|

E5 |

| - Scene 4 - No. 18 Romance: "In

Mohrenland gefangen war ein Mädel hübsch

und fein" - (Pedrillo) |

2' 37" |

|

E6 |

| - Scene 4 - Dialog: "Sie macht

auf, Herr! Sie macht auf!" - (Pedrillo,

Belmonte, Konstanze) |

0' 35" |

|

E7 |

| - Scene 5 - Dialog: "Lärmen

hörtest du? Was kann's denn geben?" -

(Osmin, Blonde, Pedrillo, Wache, Belmonte,

Konstanze) |

0' 21" |

|

E8 |

| - Scene 5 - No. 19 Aria: "O, wie

will ich triumphieren, wenn sie euch zum

Richtplatz führen" - (Osmin) |

3' 26" |

|

F1 |

| - Scene 6 - Dialog: "Geht,

unterrichtet Euch, was der Lärm im Palast

bedeutet" - (Selim, Osmin, Konstanze,

Belmonte) |

2' 13" |

|

F2 |

| - Scene 7 - No. 20 Recitativo e

Duetto: "Welch ein Geschick! o Qual der

Seele!" - "Meinetwegen sollst du sterben!"

- (Belmonte, Konstanze) |

10' 36" |

|

F3 |

| - Scene 8 - Dialog: "Ach Herr!

Wir sind hin!" - (Pedrillo, Blonde) |

1' 43" |

|

|

F4 |

| - Scene ultima - Dialog: "Nun,

Sklave! elender Sklave!" - (Selim,

Belmonte, Konstanze, Pedrillo, Osmin) |

|

|

| - Scene ultima - No. 21a

Vaudeville: "Nie werd' ich deine Huld

verkennen, mein Dank bleibt ewig dir" -

(Konstanze, Blonde, Belmonte, Pedrillo,

Osmin) |

5' 28" |

|

|

F5 |

| - Scene ultima - No. 21b Chor

der Janitscharen: "Bassa Selim lebe

lange!" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Reichmann, Bassa Selim |

|

| Yvonne

Kenny, Konstanze |

|

Lillian

Watson, Blonde

|

|

Peter

Schreier, Belmonte

|

|

| Wilfried

Gamlich, Pedrillo |

|

| Matti

Salminen, Osmin |

|

|

|

Chorsolisten und Chor des

Opernauses Zürich / Erich Widl, Einstudierung

|

|

| Mozart-Orchester

des Opernauses Zürich |

|

| Soloquartett

"Marternarie" / Frank Gassmann, Violine

/ Luciano Pezzani, Violoncello /

Thierry Fischer, Flöte / Michael

Kühn, Oboe |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

Opernhaus,

Zurigo

(Svizzera) - 1985

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 8.35673 ZB - (3

cd) - 48' 26" + 41' 40" + 45' 16" - (p)

1985 - DDD

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Teldec - 6.35673 GK - (3 lp) -

48' 26" + 41' 40" + 45' 16" - (p) 1985 -

Digital

|

|

|

Comment on the

performance of Mozart's "Entführung

aus dem Serail"

|

Even a casual glance

at the score reveals an exceptionally

rich and sophisticated orchestration

unlike any that Mozart had previously

employed, Apart from the "Turkish

music", which will

be dealt with later, it is the wind

instruments in particular which are

used in the most colourful

combinations imaginable. Mozart

specified four different types of

clarinet: in C, in B flat, in A and

basset horns, i,e. clarinets

in F. The clarinets in C, in

particular, which unfortunately are no

longer used in classical music (with

the exception of a few late romantic

operatic solos) produce a timbre that

is quite strange to present-day ears;

their jaunty sound is only to be heard

in folk music.

There is a pronounced tendency

nowadays to unify different tonal

colours and to play everything,

wherever possible, on B flat

clarinets. This has deprived the

clarinet family of its variety with

regard not only to

tone colouring, but also to

intonation. Mozart's clarinetists had

to move very rapidly from one extreme

to the other. For example, in aria No.

10 "Traurigkeit" they

play basset horns, the lowest and most

dark sounding type of clarinet,

whereas aria No. 11, "Martern

aller Arten", which

immediately follows it, is played on

clarinets in C, the brightestsounding

member of the family. In

this way Mozart achieves considerable

contrasts by variation in tone

colours.

Mozart's writing for the horns was

also extremely differentiated. He

specified horns in B flat, A, G, F, E

flat, D and C - in a

word, the complete scale of B

flat. It is exciting

for the listener as well as for the

performer to discover that the

composer did not indicate the register

of the horns in B flat, so that in

five numbers (Nos, 2, 6, 10, 15 and

20) one has to rely on the context to

determine in which octave the horns

were intended to play. (In

Mozart's time the register of the

horns in C and B flat was not abvious;

they could be played "alto"

without a crook at all or with a very

short crook, or "basso" with a very

long crook. As a rule the horns in C

were played low, and the horns in B

flat were played high, but there were

many exceptions.) However, the

register of the horns profoundly

affects the sound pattern, indeed the

harmonies, because the second horn, if

played "basso", often

drops below the bassoons. We have

attempted to find a sensible rule

that might enable the horn player to

determine in which register he was

supposed to play in places where the

composer did not indicate "alto"

or "basso",

as is the case here. In No. 2

we decided for low horns

because of the hint in bars 76-80,

where Mozart requires a conversion to

E flat horns: the first horn’s E flat

would have been a very muffled stopped

note on the low B flat instrument; in

addition, an extreme and very risky

change of register would be required.

Bar 76 on low B flat horns; on high B

flat horns; and on E flat horns, as

written by Mozart.

With the exception of these bars the

piece is therefore played in low

register. No. 6 is low (otherwise

there would be a large number of pedal

notes); No. 10 is high (because of the

combination with other wind

instruments and the harmony -

immediately obvious on account of the

whole piece being in a somewhat lower

register); No. 15 is low (because of

the harmony and the register, but

especially because of the horns' role

in the wind ensemble of the allegretto

passage in 3/4 time); No.

20 is high (here I felt that the

interplay with the clarinets in B flat

in bars 110ff, 135ff and 170ff and the

epilogue demand the high register, as

does the bright woodwind sound at "Wonne..."

at bar 26 and analogous passages).

The "Turkish"

instruments to which Mozart

occasionally refers in the score as

"Turkish Music" present a special

problem. They are the big drum, called

"tambura granda" and "tamburo

turco", the "triangoli",

the "piatti" or cymbals and the "flauto

piccolo". To understand these

instruments and their

deployment one needs to study their

provenance and role in the music of

the time. It is a

remarkable fact that until the

invasion by the "Turkish

music" there were no unpitched

instruments in the classical orchestra

at all. By contrast

with, say, the timpani, "Turkish"

instruments do not produce notes but

noise with highly sophisticated

colouring. Just as

the Turks used "Janissary

music" to inspire their own soldiers

while terrifying the enemy’s, it was

primarily adopted in the West for

military purposes. When, during the

course of the 18th century, the menace

of Turkish invasion receded, the

dangerous, spicy sounds and wicked,

exotic colours became, as it were,

succulent morsels to be savoured by

connoisseurs. Many operas by Gluck and

others are on that level.

But when Mozart and Haydn brought

Turkish instruments into play in the "Entführung"

and the "Military

Symphony", entirely new elements of

humanism and ethics were introduced.

They were not interested in

pleasurable thrills and fashionable

novelties. The essence of percussion

instruments is confrontation, indeed

aggression: the drums are always being

beaten for someone and against someone.

The more they enhance the courage and

fury of the one, the greater is the

fear that they instil in the other. At

the very first performance of the "Mi1itary

Symphony" the public was quite

horror-struck when the Turkish

instruments suddenly instruded into

the wonderfully peaceful andante. No

doubt the audience at the first

performance of "Entführung"

experienced similar emotions when,

after eight pleasurably exciting bars

in C major, played piano, the

relentless, brutal military arsenal of

Turkish instruments burst forth.

Directly and unexpectedly there

follows the central section of the

overture, in C minor, anticipating in

its musical hopelessness the words of

Belmonte’s opening arietta: Hier soll

ich dich denn sehen (Is it here that I

shall see you). The stress must lie on

"hier" - in this place where brutality

reigns, where people ar

beaten. The central section is like a

delicate plant that is crushed,

shattered by the two blocks in C

major. After the triangle's last

threatening sounds have faded away,

the central theme returns, this time

in C major; now the stress is one the

word "sehens"; it

implies "to see again",

and the music, too, expresses hope. -

This overture, of which arietta No. 1

forms a part, lays down the ground

rules, rather like a characterising

chord, of the drama which follows. Just

a brief explanation of the instruments:

The flauto piccolo is not a Turkish

instrument at all; evidently

Mozart used it on account of its

piercing sound and military

associations. This piccolo flute was

not a small transverse flute but a

special member of the recorder

family, a "flageolet"

in G which, in spite of its extremely

simple construction, has a wider range

and shriller sound than even the

modern piccolo. The tonal quality is

piping, the loudness cannot be changed

without affecting the pitch. - The

triangle: On occasion Mozart wrote "triangoli",

which suggests that he was calling for

more than one instrument.

Since, however, a

single player cannot properly control

several triangles, and experiments

proved that rather than obtaining the

required dynamic nuances their sound

became obtrusive, we

decided in favour of a single

instrument. The piatti in the "Janissary

music" were small, saucer-shaped

instruments with broad rims rather

like plates, cast in bronze, with a

wide spectrum of sounds, in which a

pitch can be discerned. It is

particularly interesting to note (and,

as far as I know, unique in classical

music) that Mozart specified two

different pitches: g” for the pieces

in C major (the overture; chorus No. 5;

No. 14; No. 21 from bar 120 onwards);

and e” for the pieces in A minor (No.

3 from bar 14 onwards; No. 21 from bar

74 onwards). This clearly implies

instruments tuned to different piches.

It is also interesting

that this is always the dominant

rather than the tonic of the piece in

question. On these cast cymbals, which

Mozart also called "Cineln"

(cinelli) the fourth is plainly

audible; thus, in the case of the

cymbals in g" one

can clearly hear the c’ and in the

case of the cymbals in e” the a’.

The tambura granda or tamburo turco is

a tall drum with a relatively small

diameter, carried across the body and

beaten by the right hand with a heavy

club-like drumstick, and by the left

with a switch or birch. The sound

produced by the club must be dry and

muffled in order to contrast

sufficiently with the timpani whenever

they play at the same time. - It is

not at all easy to achieve an entirely

unpitched sound. - When this drum

plays on its own one immediately is

put in mind of someone being beaten or

whipped. - The two types of drumbeat

are normally indicated in the score by

different note tails: J = whip, p

= club. Remarkably, and strangely in

the light of present-day appreciation

of these percussion instruments, the

first beats require the bright sound

of the whip; this is evidently of

considerably greater significance,

quite apart from being more

frightening, than the muffled thud.

All the Turkish instruments were

specially manufactured for this

performance.

The two central arias of this opera,

Konstanze's so-called "Marter" aria,

No. 11, and

Belmonte’s aria No, 17 "lch

baue ganz auf deine Stärke"

are structurally similar in that in

each case the singer is counterposed

to a group of instmmental

soloists. This idea had already been

put into practice by Mozart in

"Idomeneo" in Ilia’s aria "Se

il padre perdei" which deals with a

similar subject, with a quartet of

solo wind players. In Belmonte’s aria,

a paean of praise to the power of love

which can move mountains, the eight

wind instruments (2 each of flutes,

clarinets in B flat,

bassoons and horns in E fiat) are also

treated as soloists, as in a wind

octet. In the absence of oboes the

sound pattern becomes positively

romantic, mostly on account of the

mixture of clarinets and horns. - The

layout of the "Martern"

aria is really just as askin to

chamber music. Although the tutti

opening leads one to expect a grand

bravoura aria in late baroque style,

within a mere three bars the strings

accompany a sensitive solo quartet

consisting of flute, oboe, violin and

cello. An exceptionally long

introduction runs the gamut of

all conceivable human emotions, the

only missing element being the oft-mentioned

cruelty. Selim loves Konstanze; it is

obvious that a man of

his high moral purpose could never

be cruel, (In this

article I can only refer to the

results and not the considerations

which have produced them.) The aria

depicts the profound conflict of two

lovers, the heart of the matter being

Konstanze’s fear of succumbing to

Selim's wooing (Nur dann würd'

ich zittern: wenn ich unteu könnte

sein - Only one thing could make me

tremble: if I were

to be unfaithful), because she already

loves him. The "tortures"

are presumably the lifelong sufferings

of lovers who may not belong to one

another, Konstanze having already

plighted her troth to

Belmonte. A striking feature of this

aria is the often recurring sighing

motif played by the four instrumental

soloists; it is marked "ad

libitum" and thereby taken out of the

context of the tempo, the resumption

of which is therefore

naturally all the more effective.

This particularly striking

modification of the tempo is just one

of the many instances which indicate

that the tempi and their adjustments

were subject to the most meticulous

calculation of their dramatic impact.

There are other passages marked "ad

libitum", "stringendo

il tempo" and an unusual number of

pauses. The frequent "tenuto"

marking (sustaining the note without

loss of volume) suggests that "non

tenuto" singing was the norm. From the

adagio C (No. 6 "Ach,

ich liebte..."; No. 10 "Welcher

Wechsel..."; No. 20 "Welch ein

Geschick...") to the presto C of the

overture there are in 21 numbers no

less than 27 different tempo

indications. The interrelation of

tempi, musical figures and musical

emotions is so compelling and

indissoluble that there is hardly any

scope for shaping the individual

tempi, once certain basic speeds have

been decided upon - possibly by

reference to the acoustics in which

the performance is to take place, the

individual voices, the size of the

cast; after that one tempo flows logically

from another.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|