|

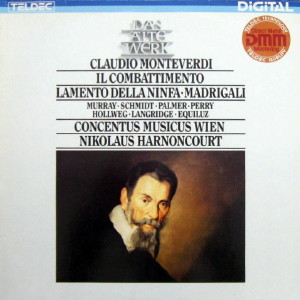

1 LP -

6.43054 AZ - (p) 1984

|

|

| 1 CD -

8.43054 ZK - (p) 1984 |

|

| Claudio

Monteverdi (1567-1643) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "Madrigali guerrieri et

amorosi..." Libro ottavo, 1638 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. Combattimento di Tancredi

e Clorinda - "Canti guerrieri"

|

21' 12" |

|

A1 |

2. Lamento della Ninfa, Rapresentativo -

"Canti amorosi"

|

5' 24" |

|

A2 |

3. Ogni amante è

guerrier - "Canti guerrieri"

|

16' 30" |

|

A3 |

4. Mentre vaga angioletta

- "Canti amorosi"

|

10' 17" |

|

A4 |

|

|

|

|

| Trudeliese

Schmidt, Clorinda (1) |

Rudolf

Hartmann, Basso (2) |

|

Kurt

Equiluz, Tancredi (1),

Tenore (2)

|

Hans

Franzen, Basso (3) |

|

Wener

Hollweg, Testo (1), Tenore

(3)

|

Janet

Perry, Soprano (4) |

|

Ann

Murray, Canto (2), Soprano

(4)

|

Felicity

Palmer, Soprano (4) |

|

| Philip

Langridge, Tenore (2,3) |

Anne-Marie

Mühle, Soprano (4) |

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine (1,3)

|

-

Ralph Briant, Cornetto (3) |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine (3) |

-

Stephan Turnovsky, Dulzian (3) |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine (3) |

-

Dietmar Küblböck, Posaune |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine (3) |

-

Joseph Ritt, Posaune |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine (3) |

-

Horst Küblböck, Posaune |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine (3) |

-

Rudolf Leopold, Violoncello

(2,3,4) |

|

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine (1)

|

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone (1,2,3) |

|

| -

Kurt Theiner, Viola (1,3) |

-

Jonathan Rubin, Theorbe (1,2,3,4) |

|

| -

Josef de Sordi, Viola (3) |

-

Jürgen Hübscher, Chitarrone (1) |

|

| -

Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Violoncello

(1) |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo

(1,2,4), Orgel (3), Truhenhorgel

(2) |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria) - febbraio

1984 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 8.43054 ZK - (1 cd) -

53' 54" - (p) 1984 - DDD

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

| Teldec "Das Alte

Werk" - 6.43054 AZ - (1 lp) - 53'

54"

- (p) 1984 - Digital |

|

|

Notes

|

In

the 16th and early

17th century particularly in

Italy and then in England,

the madrigal

was the most important

musical form, music being an

integral part of

contemporary court life. At

the same time, the extent of

its popularity and its lack

of restrictive link with

liturgical convention made

it an important vehicle for

experimental composition and

new ideas. Claudio

Monteverdi, admiringly called

by his contemporaries

“oracolo della

musica”, exerted

a decisive influence

on the whole course of

musical history. A “conservative

revolutionary”, like all

great revolutionaries,

gradually he brought about a

change in European musical

style during a long

continual process, a process

of change particularly well

demonstrated in his nadrigal

works.

Monteverdi occupied himself

with the madrigal well nigh

all his life: in 1587, when

he was twenty, he published

his first book of madrigals,

five years before his death his

eighth book

was published.

In

his Fifth Book of Madrigals

(1605) Monteverdi

introduced the use of an

accompanying basso continuo.

In defending this innovation

in his preface to the book,

against the attacks of

critical protagonists of

pure counterpoint, he made

this now famous statement:

“l’oratione sia padrona del

armonia e non serva" (“The

text should be the master, not

the servant of music”).

Fully aware of its modernity

he named his new way

of writing Seconda

prattica (“second way”), as

opposed to the older Prima

prattica (“first Way”) - the

school of strict

counterpoint. Two years

later, in 1607, he composed

his first dramatic work,

“Orfeo”. Through the great

variety of forms it

contains, both structurally

and musically this work

surpasses anything

previously written in the

older declarnatory

style of the Florentine Camerata,

and obviously owes much to

the preceding work done in

his madrigals. In

his Sixth Book of Madrigals

(1614), Monteverdi

for the first time abandoned

the traditional five-part

structure of the madrigal,

trying out various settings,

sometimes in a

soloistic-virtuoso style

(stile concertato).

The Madrigal Book VII

and VIII are of particular

value because they disclose

the pattern of development

of Monteverdi's dramatic

style. Unfortunately, through a

turn of fate, of the other

numerous dramatic works

written between “Orfeo” and

the two late Venetian operas

“Il ritorno d’Ulisse in

patria” (1641) and “L’Incoronazione

di Poppea” (1642) little is

now extant.

The Eighth Book of Madrigals

appeared in 1638, during the

Thirty Years’ War, under the

title of “Madrigali guerrieri,

et

amorosi / con alcuni

opusculi in genere

rappresentativo, che saranno

per brevi Episodii fra i

canti senza gesto” and

dedicated to Emperor

Ferdinand III.

By “canti senza gesto” are meant

the “non-gestic” madrigals

of the collection. Of the

pieces composed “in genere

rappresentativo” (“in

dramatic style”) should be

mentioned particularly the

“Combattimento di Tancredi

et Clorinda”. The

“Combattimento” is the

setting of a piece of

Torquato Tasso’s epic poem

“Gerusalemme liberata”

(verses from Canto XII). Its

completely unschematic

construction fits it into no

particular musical category,

though it is sometimes

called a “scenic madrigal”

or “scenic cantata”, and it

has not etablished any new

form in itself. lt is,

however, one of Monteverdi's

most famous

works and has, through its

subtle musical-pictorial

setting of the words

and dramatic effects,

retained its ability to

achieve an immediate impact

even today. To his Eighth

Book of Madrigals

Monteverdi added a lenghty

introduction in which he

clearly defines his position

regarding; the works

published.

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|