|

3 LP -

6.35603 GX - (p) 1983

|

|

| 3 CD -

8.35603 ZB - (c) 1984 |

|

| Georg Friedrich

Händel (1685-1759) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Concerti grossi op, 6 Nr.

1-12 |

|

|

|

Twelve grand Concertos in

seven Parts for four Violins, a Tenor

Violin, a Violoncello with a thorough Bass

for the Harpsichord

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Concerto grosso I G-dur,

op. 6 Nr. 1 |

|

12' 26" |

A1 |

| - A tempo giusto |

1' 44" |

|

|

- Allegro

|

1' 37" |

|

|

| - Adagio |

2' 54" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 39" |

|

|

- Allegro (Menuet)

|

3' 32" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso II F-dur,

op. 6 Nr. 2 |

|

12' 11" |

A2 |

- Andante larghetto

|

3' 43" |

|

|

- Allegro

|

2' 53" |

|

|

| - Largo -

Adagio/Larghetto andante e piano |

2' 38" |

|

|

- Allegro ma non troppo

|

2' 54" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso III

e-moll, op. 6 Nr. 3 |

|

11' 33" |

B1 |

| - Larghetto |

1 15" |

|

|

- Andante

|

1' 36"

|

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 38" |

|

|

- Polonaise: Andante

|

4' 28" |

|

|

- Allegro, ma non troppo

(Menuet)

|

1 36" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso IV

a-moll, op. 6 Nr. 4 |

|

12' 38" |

B2 |

| - Affettuoso |

3' 13" |

|

|

- Allegro

|

3' 32" |

|

|

- Largo e piano

|

2' 43" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

3' 10" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso V D-dur,

op. 6 Nr. 5 |

|

18' 17" |

C1 |

| - Larghetto e staccato |

2' 01" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 00" |

|

|

| - Presto |

4' 06" |

|

|

| - Largo |

2' 34" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 32" |

|

|

- Menuet: Un poco

larghetto

|

3' 04" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso VI

g-moll, op. 6 Nr. 6 |

|

16' 45" |

C2 |

| - Largo affettuoso |

3' 43" |

|

|

| - A tempo giusto |

1' 46" |

|

|

| - Musette: Larghetto |

5' 23" |

|

|

- Allegro

|

3' 33" |

|

|

- Allegro (Menuet)

|

2' 20" |

|

|

Concerto grosso VII

B-dur/d-moll, op. 6 Nr. 7

|

|

14' 08" |

D1 |

| - Largo |

1' 17" |

|

|

- Allegro

|

3' 22" |

|

|

| - Largo |

2' 18" |

|

|

| - Andante |

3' 56" |

|

|

| - Hornpipe |

3' 15" |

|

|

Concerto grosso VIII c-moll,

op.6 Nr. 8

|

|

17' 39" |

D2 |

| - Allemande |

7' 34" |

|

|

| - Grave |

1' 39" |

|

|

| - Andante allegro |

1' 48" |

|

|

| - Adagio |

1' 10" |

|

|

| - Siciliana |

4' 00" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

1' 28" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso IX F-dur,

op.6 Nr. 9 |

|

12' 44" |

E1 |

| - Largo |

1' 10" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

3' 42" |

|

|

| - Larghetto |

2' 34" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 08" |

|

|

| - Menuet |

1' 09" |

|

|

| - Gigue |

2' 01" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso X d-moll,

op.6 Nr. 10 |

|

14' 46" |

E2 |

- Ouverture - Grave

andante/Allegro

|

3' 59" |

|

|

- Air: Lent

|

3' 48" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 08" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

3' 25" |

|

|

- Allegro moderato

|

1' 26" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso XI A-dur,

op.6 Nr. 11 |

|

16' 44" |

F1 |

- Andante larghetto e

staccato

|

4' 39" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

1' 44" |

|

|

- Largo e staccato

|

0' 33" |

|

|

| - Andante |

3' 40" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

6' 08" |

|

|

| Concerto grosso XII h-moll,

op.6 Nr. 12 |

|

10' 33" |

F2 |

| - Largo |

2' 07" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 55" |

|

|

| - Aria: Larghetto e

piano |

2' 36" |

|

|

| - Largo |

0' 40" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 15" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

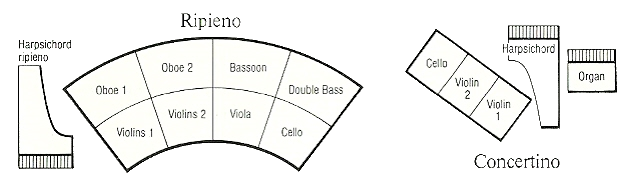

| Ripieno |

Concertino |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine (VII) |

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine

|

|

| -

Thomas Zehetmair, Violine

(III/4,5; VII; IX/4,5,6) |

-

Erich Höbarth, Violine (I; VI;

IX/1,3; X)

|

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Anita Mitterer, Violine (II-V;

VIII; XII)

|

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Thomas Zehetmair, Violine (X) |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Wolfgang Aichinger, Violoncello

(I; IV; X) |

|

-

Anita Mitterer, Violine (I; VII;

IX-XI)

|

-

Christophe Coin, Violoncello

(II; III/1-3; V-VII; IX; XII) |

|

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine (I-II;

IV-VI; IX-X)

|

-

Rudolf Leopold, Violoncello

(III/4,5; XI) |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo, Orgel |

|

-

Wolfgang Trauner, Violine (II;

V-IX; XII)

|

|

|

-

Herlinde Schaller, Violine

(III/1,2,3; VII-VIII; XII)

|

|

|

-

Erich Höbarth, Violine (IV)

|

|

|

| -

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

|

|

| -

Peter Waite, Viola (II; VI) |

|

|

| -

Josef de Sordi, Viola |

|

|

| -

Christophe Coin, Violoncello

(VII/1,2) |

|

|

| -

Fritz Geyerhofer, Violoncello

(I; III/4,5; IV; VI; IX-XI) |

|

|

| -

Wolfgang Aichinger, Violoncello

(II; V) |

|

|

| -

Mark Peters, Violoncello

(III/1,2,3; VII; VIII; XII) |

|

|

| -

Rudolf Leopold, Violoncello

(VII/3,4,5) |

|

|

| -

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

|

| -

Jürg Schaeftlein, Oboe (I-VI;

VIII-IX; XII) |

|

|

| -

Valerie Darke, Oboe (I; IV; VI;

IX/1,2,3) |

|

|

| -

Marie Wolf, Oboe (II-III; V;

IX/4,5,6; XII) |

|

|

| -

Milan Turković, Fagott (I-III;

V/1,2; VI-IX; XII) |

|

|

| -

Otto Fleischmann, Fagott (IV;

V/3,4,5) |

|

|

| -

Heebert Tachezi, Cembalo (VII;

X) |

|

|

| -

Lisa Autzinger-Kubizek, Cembalo

(I-II; IV; V) |

|

|

| -

Gordon Murray, Cembalo (III;

VIII; IX/4,5,6; XI) |

|

|

| -

Glenn Wilson, Cembalo (VI;

IX/1,2,3) |

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Casino Zögernitz,

Vienna (Austria) - 1982

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 8.35603 ZB - (3 cd) -

49' 17" + 65' 11" + 55' 17" - (c) 1984 -

DDD

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Teldec "Das Alte

Werk" - 6.35603 GX

- (3 lp) - 49'

17"

+ 65' 11"

+ 55' 17" - (p) 1983

- Digital

|

|

|

Comments on the

Performance

|

Handel’s

twelve Concerti

grussi op. 6 were virtually

all written at the

same time, between

29th September and

30th October 1739. This is

not at typical method of

working, since he

usually availed himself of all manner

of earlier

works whenever

he was publishing a new

opus. (Even the

Concerti grossi op.

6 include the odd

movement culled from

another composition, but

nowhere near

as much as do

orher comparable works.) This

homogeneous burst of creativity is

just as much a charatceristic

of the

twelve concertos as is their

homogeneous scoring: in the first

place only the strings and a chordal continuo

instrument are indispensable.

Although Handel added autograph

wind parts to some of the

concertos they are always of an ad

libitum type and can therefore be

omitted without impairing the

substance of the work; they do,

however, give a clear indication

of Handel's procedure when

enlarging his scoring, and we have

added in the wind parts where we

felt that it would have

corresponded to his own ideas.

In these Concerti

grossi Handel departed from the

strict forms then in use, of which a

choice of three was

available to him: (1) the old sonata

da chiesa, in which the

arrangement of movements is slow -

fast - slow - fast (and where a slow

movement might be reduced to

a mere few introductory

bars); (2) the

modern Italian concerto form of

Vivaldi (with a substantial

independent slow movement); (3) the

French orchestral suite with an

introductory overture and a large

number of dance movements. But Handel

grouped the movements differently for

each of these concertos

by combining these

traditional layouts at his own

discretion.

Handel seems to have had a great

fondness for concluding technically

demanding and stirring concertos with

an innocent, light dance movement,

preferably a minuet. This

is totally at variance with

our notion of an “effective“

conclusion that calls for applause.

The listener was not to be sent away

in an excited frame of mind; his

feelings had rather to be returned to

a state of equilibrium, after

having been presented with a great

variety of musical emotions. Thus

recovery, calmness and ordering of

feelings after enthusiasm and excitement

are more or less

written into the music.

Certainly Handel wanted to

move and inspire his public and no

touch tender spots, but he also wished

to restore them and to send them away

in a harmonious frame of mind.

The original title of the first

edition, published under the

composer’s supervision

by Walsh m 1740, read: “TWELVE GRAND

CONCERTOS IN SEVEN PARTS FOR FOUR

VIOLINS, A TENOR VIOLIN, A

VIOLONCELLO WITH A THOROUGH

BASS FOR THE

HARPSICHORD. COMPOS`D BY

GEORGE FREDERICK HANDEL.

PUBLIISHED BY THE

AUTHOR. LONDON...". There

is no mention of the oboe parts

already referred to, nor of the

figuring of the solo cello part, which

would imply a second continuo

instrument. Clearly Handel chose the

version which was simplest and thus

most likely to sell, since the

different possibilities and the contemporary

performance practice for this type of

concerto since thec days of Corelli

and Muffat was widely known, so that

musicians could adapt

the scoring in rhs light

of the forces at their disposal and

where the work

was to be played.

Since Handel's Concerti grossi are

intimately related to

those of Corelli, the

"inventor" of

Concerto grosso, their performance

practice is also likely to

have been similar.

Fortunately a highly reliable witness

has not only copied

Corelli's style m his own works

but also described

it: Georg Muffat, despatched

by the Archibishop of Salzburg to

Rome to study the Italian

style, moved in Corelli’s circle and

was able to hear his first Concerto

grosso played under the

direction of the composer.

This inspiredl

him to write

similar worlks: "lt is

that these fine concertos which I

enjoyed in the new

genre in Rome, encouraged me

greatly in that they

inspired some ideas

within me..." and

later: "The first

thoughts came to me... in Rome...

where I... had heard that type of

concerto composed by

the ingenious Archnigelo

Corelli with great pleasure and

amazement." He went on to

describe the various ways in which

they might he performed: “They can be

played merely a tre..."

(this texture is particularly

appropriate to Handel’s concertos

because they were conceived decidedly

in the style of a trio sonata, the

viola parts only being added in at the

end of the process of composition; for

that reason they sometimes appear

quite indispensable, and on other

occasions they show through the gaps

in the fabric like foreign bodies, not

fitting logically into the

part-writing.) - “They can also be

played... a

quattro" simply by combining

tutti and soli, - “if

you can place them in the complete Concertino

a tre with two

violins and a violoncello“

opposite the "Concerto grosso“, the

Tutti orchestra, in which the violas

are doubled “in due

proportion", i. e. depending on the

number of first and second violins

available. - The

concertos can therefore be performed

by any size of orchestra ranging from

tiny to very large, and indeed we know

that this is what Corelli did. - On

the title page of

his Concerti grossi of 1701 Muffat

wrote that they could be played with

small forces, “but that they would

be... much finer if divided into...

two choirs, a large one and a small

one“. Moreover, the Concertino, the

trio of soloists, “was to play on its

own, accompanied by an organist“, i.

e. with its own continuo instrument

(this explains Handel's

figuring of the continuo cello part in

the autograph and in other sources).

Muffat even mentions the (ad lib.)

addition of oboes: “But if... some are

able... to play... the French

hautbois... sweetly..." In

certain circumstances he is even

minded to hand over the

solo trio to them along with a

“competent bassoonist“. - These highly

flexible alternative methods of

attaining optimum interpretation

remained an essential characteristic

of the genus Concerto grosso. This

means that various types of

performance practice from Corelli to Handel

and beyond have survived; several

generation understood by the term

“Concerto grosso“ not only a certain

kind of instrumental music, but also

the appropriate method of performing

it.

In this context the

positioning appears to me to be

crucial. Contemporary sources

repeatedly refer to the fact that

choirs (in this case groups of

instruments) were placed far apart,

sometimes separated by the whole

length or width of the room. - The

point is that if the Concertino

(the trio of soloists) is manned by

the principals of the orchestra, as

unfortunately so often happens

nowadays, many of the effects which

are quite obvious from the score, i.

e. intended by the composer, make no

sense at all. This is the case in the

second half of each of the first three

bars in Concerto No, 1, where moreover

the two solo violins are playing in

unison. This allocation of parts is

pointless if they are

played from the body of the orchestra;

but if the Concertino is placed at a

distance from the

Tutti the

effect is that of

a dialogue, and there

are many sirnilar instances.

The normal interplay

of Ripieno and Concertino

also requires physical separation

in order to be

effective.

We experimented with various layouts

in the concert hall and came to

the conclusion that

in Concertos Nos. 1,

2, 4, 6, 9 and 10 the composer’s

intentions

are best realised if the

Concerrino wich its own continuo

instrument

is placed an the back

and no the right, that

is to say

not only further away

from the audience than

the Ripieno, but also

offcentre.

On the one hand this puts into sharp

relief the

Continuo/Ripieno dialogue; on the

other hand it was

only in these circumstances

that

sound effects

in some movements (e. g. Concerto

No. 2, fourth movement,

bars 27-40 and similar passages;

Concerto No. 5, fourth movement et

al.) really make sense. In addition,

those passages in which Concertino and

Ripieno play togheter achieved a

peculiar and very convincing timbre

because the whole body of sound was,

as it were, contained by the continuo

instruments, and the upper part did

not come exclusively from the left as

is usually the case, but also from the

far right at the back. This created a

highly individual spatial sound

effect. - In the recording studio this

layout also proved to be the most

convincing not only to highlight the

dialogue texture, but also for reasons

of sound control. In Concertos Nos. 3,

5, 7, 8, 11 and 12 the Concertino was

also placed on the right, but not

quite as remote from the Ripieno.

The Continuo was handled

differently from one concerto to the

next, indeed from one movement to

the next: on the whole an Italian

continuo harpsichord with an edgy,

brilliant timbre was used with the

Ripieno and a dark, gentle

Franco-Flemish harpsichord

with the Concertino. In

some movements the Concertino

was accompanied by an organ, some

movements were played only with a

harpsichord or only with

an organ.

Regarding the use of wind

instruments, it is

well known that Handel, and

indeed many contemporary composers and

English precursors such as Henry

Purcell, frequently used

oboes and bassoons

without explicitly stating it in the

score; the criteria evidently being the

size of the orchestra and the forces

available.

In Concertos Nos. 1, 2, 5 and 6

we were able to adhere to Handel's wind

parts, placing the oboes with

the violins and the

bassoon with the bass instruments of

the Ripieno. According to Handel’s

principles the oboes and the

bassoon appear to be intended

to impart body and

outline to a heavily

scored Ripieno,

to add brilliance to

the coloratura by attacking

the appropriate opening

and closing notes and

to make the

texture more intelligible in

complicated figurations by playing the

bass line unadorned. In accordance

with these guidelines we have added

oboes and bassoons in Concertos Nos 3,

4 (second and fourth

movement), 5, 8 (only one

oboe in the first, third, fifth and

sixth movement), 9 and

12. Concertos Nos. 7, 10 and 11

we consider to be

string concertos pure and simple, on

account of their

range and the part-writing of the

violins. (ln Nos. 7 and 10 we added a

bassoon for reasons of

sonority.)

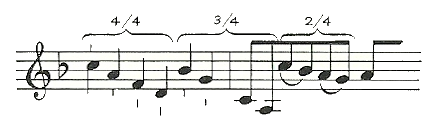

I would also like to

draw attention to a peculiarity of baroque

notation which is particularly

prevalent in Handel’s works

but is regrttably

widely disregarded: the

combination into "macro bars"

which substantially determines

articulation, phrasing and mainly

tempo. Unfortunately

this kind

of notation, graphic though it

is to any musician, is suppressed

in virtually all modern editions, so

that it is impossible to discover

what the composer actually wrote.

This combination of several bars was

expressed by indicating the

"ordinary" metre (say 3/4) in the

time signature, bar lines only being

written about every four bars or so,

sometimes erratically. Some

musicologists take the view that

this was just a convenience because

passages with very small note values

could be more readily accommodated

by this method; we are convinced

that this is a distinct idiom which

ought to be shown in the actual

notation and not just mentioned in

the notes on the edition. The

following movements of Handel's op.

6 are notated in this manner:

Concerto No. 2, fifth movement

(in this movement the

metre is

particularly interesting because in

terms of stress it begins

in 4/4, followed by 3/4 and 2/4. Incidentally, Handel

deleted his original time signature

of 6/4 which indicates where the stresses fall, without replacing it!) No. 4, second

rnovement: the time signature in C,

but bar-lines occur only every

fourth bar (this is

another cornplicated

polymetric structure which is

rendered incomprehensible by bar-lines). No. 5,

third movement: time signature 3/s,

bar-lines every fourth bar (creating

an unmistakeable 12/8 metre, with the 3/8

indication presumably intended to

curb the headlong presto). Fourth

movement: time signature

3/2, bar-lines every

fourth bar (to prevent stressing

individual bars

and to suggest a spacious so to

speak 12/2 tempo). No. 6, second, third

and fifth movement: time signature

C, 3/4, 3/8, erratic bar-lines but

predominantly every fourth bar, depending on the

phrasing. No. 8, fourth movement: time signature 3/4

(a sort of 12/4 metre is created,

bar-lines every fourth bar. Fifth movement: time

signature 12/8, bar-lines every

other bar. No. 9, first and second

movement: time signature 3/4 and C, bar-lines every

fourth bar. No. 10, second movement:

time signature

3/2, bar lines every fourth bar.

Fourth movement: time signature 3/4,

erratic bar

lines but predominantly

every fourth bar.

No. 11, first movement: time

signature C, bar-lines every other

bar. Fourth and fifth

movement: time signature 3/4 /the

indicated 12/4

metre quickens the tempo) and C,

bar-lines every

fourth bar. No. 12,

first movement: time signature C,

bar lines every other

bar. Third movement: time

signature 3/4, bar-lines every

fourth bar. (the

indicated 12/4

melody requires a faster tempo than

a normal 3/4 larghetto

because the metre becomes the

beat) Fifth

movement: time signature C,

bar-lines every other bar. In

Concerto No. 9

there is no double

bar between the second

(allegro) and third

(larghetto) movement but an ordinary

bar-line, i. e.

they form a pair. The first of these

two movements is,

like the Organ concerto "The cuckoo

and the nightingale", doubtless inspired by birdsong and

the rustle of the forest; the

musical imagery is presumably

firther enhanced by the pastoral

Siciliano, suggesting open

meadows.

Of course we have

supplied not only most of the

phrasing slurs in accordance

with the rules then prevailing,

but also many trills, their

preparatory turns and

appoggiaturas. All cadenzas and

ornaments were freely, improvised.

Nikolaus

Harnoncort

Translation:

Lindsay Craig

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|