|

1 LP -

6.42756 AZ - (p) 1982

|

|

| 1 CD -

8.42756 ZK - (c) 1983 |

|

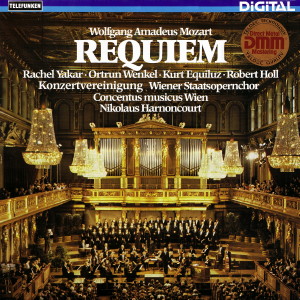

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Requiem d-moll, KV 626 |

|

|

|

| Ergänzungen von Xaver

Süßmayr - Neue Instrumentierung von

Franz Beyer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I. Introitus:

Requiem: Adagio |

|

4' 16" |

A1 |

| II.

Kyrie: Allegro |

|

2' 40" |

A2 |

| III. Sequenz: |

|

19' 13" |

|

| - Dies irae: Allegro

assai |

1' 49" |

|

A3 |

| - Tuba mirum: Andante |

3' 41" |

|

A4 |

| - Rex tremendae |

1' 53" |

|

A5 |

| - Recordare |

6' 18" |

|

A6 |

| - Confutatis: Andante |

2' 38" |

|

A7 |

| - Lacrimosa |

2' 54" |

|

A8 |

| IV.

Offertoriun: |

|

6' 45" |

|

- Domine Jesu

|

3' 45" |

|

B1 |

| - Hostias |

3' 01" |

|

B2 |

| V. Sanctus |

|

1' 25" |

B3 |

| VI. Benedictus |

|

5' 14" |

B4 |

| VII. Agnus Dei |

|

3' 18" |

B5 |

| VIII. Communio: Lux

aeterna |

|

5' 22" |

B1 |

|

|

|

|

| Rachel Yakar,

Sopran |

|

Ortrun Wenkel,

Alt

|

|

Kurt Equiluz,

Tenor

|

|

Robert Holl,

Baß

|

|

|

|

Konzertvereinigung Wiener

Staatsopernchor / Gerhard Deckert, Choreninstudierung

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

-

Philip Saudek, Viola |

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violine |

-

Peter Waite, Viola |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Heidi Litschauer, Violoncello |

|

| -

andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Fritz Geyerhofer, Violoncello |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Kontrabaß |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Kontrabaß |

|

| -

Herlinde Schaller, Violine |

-

Hans Rudolf Stalder, Bassetthorn |

|

| -

Peter Katt, Violine |

-

Elmar Schmid, Bassetthorn |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Milan Turković, Bassetthorn |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

-

Danny Bond, Bassetthorn |

|

| -

Wilhelm Mergl, Violine |

-

Hans Pöttler, Posaune |

|

| -

Gottfried Justh, Violine |

-

Ernst Hofmann, Posaune |

|

| -

Wolfgang Trauner, Violine |

-

Horst Küblböck, Posaune |

|

| -

Manfred Heinel, Violine |

-

Hermann Schober, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Richard Motz, Violine |

-

Richard Rudolf, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

-

Kurt Hammer, Pauken |

|

| -

Josef de Sordi, Viola |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Orgel |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Grosses

Musikvereinssaal, Vienna (Austria) -

novembre 1981

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 8.42756 ZK - (1 cd) - 48' 47" - (c)

1983 - DDD |

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Telefunken - 6.42756

AZ - (1 lp) - 48'

47"

- (p) 1982 - Digital

|

|

|

Mozart's Requiem Mass

|

In Mozart’s day

composers wrote sacred music as it

matter of conrse. He too conformed to

this practice, generally accepting

e.g. in his Masses liturgical

requirements or musical traditions.

Some of his sacred works, however,

far exceed what had become standard

expectations; among these is the

“Requiem”, combining traditional

thoughts handed down from the past

with new ones, brought together within

the common denominator of his own

style and making the

motto “Opus summum viri summi” which

J. A. Hiller wrote at the

head of his own copy,

appropriate from many aspects.

On the one hand the influence of Bach

and Handel is obvious in the

counterpoint and rhetoric; on the

other, in his harmonies and colours

Mozart looked well forward into the

l9th century, thus creating a

synthesis of both style and character

in which the archaic is joined

to the subjectively emotional. The

opening of the “Requiem” extends, in

its expressiveness, far beyond the

liturgical framework into the realms

of an essentially personal creed. The

predominance of basset horns and

bassoons indicates, particularly in the

first part, a romantic sonority of

subjective resignation which

corresponds to Mozart`s own views on

death as set out in a letter to his

father dated 1787.

Even so, Mozart, who never balked at

presenting man’s most pronounced

feelings, contrasted the conciliatory

attitude at the beginning with

individual revolt: the orchestral

figures at “Exaudi orationem

meam” are of an almost waspish obduracy.

The romantic aspects of the

work are exemplified by the “Kyrie”

fugue with its bold harmonic

excursions which characterise the

dark, profound aspects. The dramatic

manner in which Mozart, in the "Dies

irae”, combined the objectively

devotional with the subjectively

devout is also highly significant.

After the passionate insistence of the

“Rex tremendae majestatis” with its

almost expressionistic emphasis on thc

tremendous, the pinnacle of the work

is reached in the humble prayer and

deeply moving fearfulness of the “Recordare”. Its

completely romantic mood is followed

by the realistically descriptive

“Confutatis maledictis“, once again

full of bold harmonies which must have

been quite intimidating in l79l and

almost foreshadow Wagner with their

chromaticism. Only the first eight

bars of the “Lacrimosa” are by

Mozart himself. The Sanctus,

Benedictus and Agnus Dei may be

based on his sketches but bear

unmistakeable marks of his 25 year

old pupil Franz Xaver Süssmayr, who

completed the torso. The quotation

of the opening, “Requiem aeternam"

in the concluding “Lux aeterna" is

said to be in accordance with the composer`s wishes. For all its

incompleteness,

the work represents a synthesis not

only of Mozart's

own achievements but also of 18th

and 19th century music.

Mozart worked on the

“Requiem” from

the summer of l791

until his death in early December of

thc same year, interrupted twice, by

the "Magic Flute” and "La clemenza

di Tito". The title page of the

“Requiem” autograph bears the date 1792

in his own hand: obviously he

planned to complete in the following year the

work which had been

begun as a result of a commission of

which the romantic circumstances

have created a whole legend. Count

Waldcgg, who

had commissioned the work, is said to

have had it performed in 1793.

Wolf-Eberhard

von Lewinski

|

|

| Some

Thoughts and Impressions on the "Reqiem"

Mozart's only work with autobiographical

elemets |

It

is not my intention to present an

analytical or musicological

study of this work, but

to set down certain

impressions which struck me as a

musician when I was preparing the

“Requiem” for several performances and

for this recording. In the

first place, in spite of its fragmentary

origins and although its completion by

Mozart’s pupil Süssmayr

has been widely castigated.

I was completely aware of' the context,

the overall design, the architecture of

the whole work much more forcefully than

in the past. I cannot

consider the additional items as musical

foreign bodies; they are essentially

Mozartian. I find it

misleading and impossible to believe

that an inferior composer such as Süssmayr,

whose works never rose

above banal mediocrity, should have been

able to complete on his own the

Lacrimosa or write this Sanctus,

Benedictus and Agnus Dei. Even

inspiration derived from the other

sections that might have lent Siissmayr

wings cannot convince me ofthe

provenance of these movements. As far as

I am concerned, they are also by Mozart,

either because Süssmayr

had the relevant sketches at his

disposal or else because Mozart had

impressed them upon him by

playing them to him during their

collaboration. The obvious discrepancy

of quality between the composition

itself and Süssmayr’s

orchestration confirms me in this view.

We know from Mozart’s letters

that thoughts of death and devout

speculation on the subject were a

familiar and quite natural experience

for him. In 1878, aged 31,

he wrote to his ailing

father: “... since death, when you come

to think of it, is actually the ultimate

purpose of our life, I

have got to know this true, best friend

of man so well that his image not only

no longer frightens me, but calms and

comforts me! And I thank

God that He has given me

the boon of providing an

opportunity to get to know him as the

key to our true happiness.

- I never go to bed without Even the

quartet from "Idomeneo",

written ten years before the “Requiem”,

strikes me as being the first,

highly personal, “coming to grips” with

his own death. Mozart, who certainly

identified himself with Idamante,

always had an exceptionally strong

emotional relationship to this opera and

particularly to this quartet. It

is reported that when he was once making

music in Vienna, presumably taking the

part of Idamante, he was

rnoved to tears to such an extent that

he could not continue singing. A similar

story is told about a “rehearsal” of the

Requiem, when the completed sections

were tried out shortly before his death;

at the Lacrimosa Mozart burst into tears

and was unable to carry on.

The whole work strikes me as an

intensely personal confrontation,

frightening and moving in the case of a

composer who normally kept his life and

experience divorced from his art to an

astonishing degree. - The instrumental

prelude is a dirge (basset

horns and bassoons) with weeping,

sobbing strings. This calm sorrow is

torn apart by the forte outburst of

trombones, trumpets and tirnpani in the

seventh bar: now death is no longer a

gentle friend, but the path to the dread

judgement. Here I have experienced for

the first time, as did perhaps Mozart

himself, the official liturgical text

becoming an intimately shattering

revelation: Death waits for us all - but

what will become of me! Or after

“luceat cis” (let perpetual light shine

upon them) in bars 17-20. when the

impassioned general plea leads into a

motif of blissful consolation, as though

to say: all will be well, because there

is mercy. - The Kyrie. the prayer for

divine mercy. arises from the general

fugue, calling with increasingly

personal, indeed demanding homophonic

cries: Lord, You must have mercy

upon me! The sequence highlights

particularly strongly the antithesis

between the general and the individual.

The Dies irae paints a merciless picture

of the terrors of the Day of Judgement.

the severity of the judge ("cuncta

stricte discussurus”). The “Tuba mirum”

wakes the dead to come to be judged,

when nothing shall remain unavenged

("nil inultum remanebit") -

followed in most moving personal terms

by the fearful question “What shall I,

wretch that I am, say then?" Or the

flagrant contrast between the mighty

King of the “Rex tremendae” with the "I"

with myself: “Fount of mercy, grant me

salvation”. In the “Recordare” a

movement which, according to Constanze,

Mozart particularly valued, the contrast

resolves into an urgent and deeply

trusting prayer: "Remember that You

redeemed me by Your suffering; this

labour must not be in vain." I fully

understand Mozart’s particular attitude

to this movement (part musical, part

religious) because it allows the

personal element in the relationship to

God to be brought out so strongly. It

also paints most tenderly the hope that

the judge, earlier described as being

inexorably strict, may show loving

clemency, especially in the two phrases

“You who pardoned Mary Magdalene, give

me hope as well” (bars 83-93) and “Let

me be at Your right hand, among the

sheep" (bar 116 to the end). In the

“Confutatis”, which a priori contains

the contrast between Everyone and I, the

intimate and personal relationship with

God is stressed in the last sentence

“Stand by me, when I die!”,

both harmonically and in the confident

and trusting setting of the text. Here I

can hear Mozart`s own voice. speaking up

on his own behalf, with all the moving

urgency at his command, like a sick

child that looks trustingly at his

mother - and fear departs.

----------

The

new instrumentation published by Edition

Eulenburg in l972 was used as the basis

for this recording.

This edition attempts to remove the

obvious errors in Franz Xaver Süssmayr`s

“routine instrumentation” (Bruno

Walter), which has been the subject of

criticism more or less since he made it

at the request of Constanze

Mozart, and furthermore to colour it

with the hues ot Mozart’s own palette.

Such a restoration of the predominantly

sumptuous, theatrical overpainting could

only mean bringing out the manuscripts

‘original state’, its status nascendi so

to speak, as clearly as possible.

In the final event, of course, we cannot

be certain that Mozart intended to

provide instrumental accompaniment for

his Requiem. The incomparable

transparency of his late works, however,

particularly the tonal concept of the

Introitus, give us at least an idea of

the course the composer would have taken

for the movements that follow.

We may be confident today that we are

gradually achieving a closer and more

conscious understanding of the Mozartean

spirit, and hope that, in an active

exposition of his last work. this is

sufficient justification for the new

instrumental clothing.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

Translation:

Lindsay Craig

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|