|

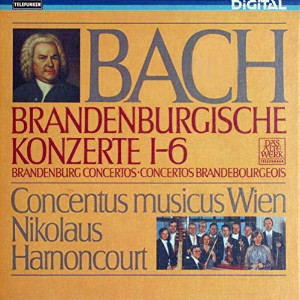

1 LP -

6.42823 AZ - (p) 1981

|

|

| 2 LP -

6.35620 FD - (c) 1982 |

|

| 1 CD -

8.42823 ZK - (c) 1983 |

|

Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) - Brandenburgische

Konzerte 1 - 2 - 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Brandenburgisches Konzert

Nr. 2 F-dur, BWV 1047 |

|

11' 46" |

A1 |

| (Concerto 2do á 1 Tromba 1

Fiauto 1 Hautbois 1 Violino, concertati, è

2 Violini 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col

Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo.) |

|

|

|

| - (Allegro) |

5' 20" |

|

|

| - Andante |

3' 28" |

|

|

- Allegro assai

|

2' 58" |

|

|

| Brandenburgisches Konzert

Nr. 4 G-dur, BWV 1049 |

|

15' 52" |

A2 |

| (Concerto 4to á Violino

Prencipale, due Fiauti d'Echo, due

Violini, una Viola è Violone in Ripieno,

Violoncello è Continuo.) |

|

|

|

- (Allegro)

|

7' 04" |

|

|

- Andante

|

3' 55" |

|

|

- Presto

|

4' 53" |

|

|

| Brandenburgisches Konzert

Nr. 1 F-dur, BWV 1046 |

|

20' 00" |

B |

| (Concerto 1mo á 2 Corni di

Caccia, 3 Hautb: è Bassono. Violino

piccolo concertato, 2 Violini, una Viola è

Violoncello, col Basso Continuo.) |

|

|

|

| - (Allegro) |

4' 05" |

|

|

| - Adagio |

4' 00" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

4' 15" |

|

|

- Menuet, Trio,

Polonesche, Trio

|

7' 40" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

| -

Hermann Baumann, Naturhorn |

-

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

|

| -

Marcus Schleich, Naturhorn |

-

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

|

| -

Friedemann Immer, Naturtrompete |

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

|

| -

Elisabeth Harnoncourt, Flauto |

-

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

|

| -

Marie Wolf, Flauto (4), Hautbois

(Nr.1) |

-

Wilhelm Mergl, Violine |

|

| -

Jürg Schaeftlein, Hautbois |

-

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

|

| -

David Reichenberg, Hautbois

(Nr.1) |

-

Josef de Sordi, Viola |

|

| -

Milan Turković, Bassono |

-

Wouter Möller, Violoncello (Nr.1) |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violino

piccolo (Nr.1), Violino conc.

(Nr.2), Violine |

-

Nikolaus Harnoncourt,

Violone/Violono grosso (Nr.1) |

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Grosses Tonstudio Rosenhügel,

Vienna (Austria) - gennaio 1981 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec "Das Alte Werk" -

6..42823 ZK - (1 cd) - 48' 25" - (c)

1983 - DDD

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

- Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" -

6.42823 AZ - (1 lp) - 48' 25" - (p) 1981

- Digital

- Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" -

6.35620 FD - (2 lp) - 48'25" + 50' 10" -

(c) 1982 - Concerti I-VI |

|

|

Notes

|

The

Brandenburg Concerti are in

fact a selection from the

music Bach composed for the

court orchestra, the Hofkapelle,

during his time at Köthen.

Bach dedicated these six

concerti, which had all been

composed some time before,

to the Margrave of

Brandenburg,

and took the opportunity to

write

all six into a combined

dedicatory

score. What I feel is

important here is that the

concerti were not, as was

usually the case, adapted to

the musical abilities of the

dedicatee; rather, they

represent a colourful

pattern book

of the composer’s

art.

One must bear this in mind

to explain the remarkable

fact that these

concerti have nothing

whatsoever in common exccpt

the names of the composer

and the dedicatee - as

individual works they are as

different

as was conceivable at the

time:

each concerto is

scored for a different

combination of instruments

and soloists; Bach follows

different structural

principles in each

case. The

concertante playing of a

soloist or group of soloists

as a dialogue or contest

with a ripieno group - in

this case a small string

orchestra - is occasionally

reduced here to a purely

formal, only musically

recognisable idea (for

example, in the slow

movement of concerto no. 5

or in the entire 3rd and 6th

concerti). These

six concerti, then,

represent in every respect

the maximum possible differentiation

and variety. Diversity

takes precedence over

uniformity.

Brandenburg Concerto no. 1 is

one of the earliest works in

musical history in which the

hand horn is employed as a

solo instrument across the

entire breadth of its

capabilities. The entry of

this instrument into the

intimate sphere of refined

salon music must have

created a sensation. The

hunting horn

(corno

di caccia) was principally

used in hunting, different

horn signals serving to keep

the widely

scattered

groups informed on the

progress of the hunt.

This genuine “open-air"

instrument was blown mainly

by the huntsmen themselves

and their attendants. Even

the

horn-players in the first

performances of Bach’s

concerto may well

have been travelling

“huntsmen-virtuosi”; this

is, at all events, made very

clear by

their entrée

in the first tutti, a real

hunting fanfare, in which the quavers

are adapted to the triplet

rhythm characteristic of the

hunt. The rest of the

orchestra, apparently

unmoved by the

horn signals with their

quite unwonted form

and rhythm, plays a quite "normal"

Bachian orchestral tutti.

The concertante playing

already stands out here

with the alternating of the

oboes

and strings in bars 6-7;

from bar 9 onwards the

horns are brought in as full

concerto partners, and Bach

uses the intonationally extreme

natural notes F, F sharp and

A (the

eleventh and thirteenth

harmonics) from the start.

Since the musical sound

groups of

"figures" in

this movement correspond to

common, well-known forms,

Bach was able to leave the

very necessary articulation

up to the musicians. We

therefore

put in and performed the

articulation markings

according to contemporary

usage. In the first movement

the concertante playing

comes out, between real

tutti blocks, as a

confrontation (something of

a vehement dialogue)

beetween the

three groups horns, woodwind

and strings. In the second

movement the solo oboe, the

violino piccolo

(a small violin, tuned a

minor third higher, which

produces an odd, acute

sound) and the bass group

imitate each other on a

refined, impressionistic

basis. Here

the most unusual

articulation is specified by

the composer. The first

four

bars belong to the solo

oboe, whose notes,

determining the harmony, are

harmonically reinforced by

the second and third oboe

and the double-basses. The

strings provide

accompaniment with the bow

vibrato so beloved at the

time for sensitive places -

these four

bars are repeated in the

upper fifth by the violino

piccolo, during which the

woodwind and the strings

exchange roles (the bow

vibrato is now a

"frémissement" on the wind

instruments). The rewith the

material which is to be

developed is set out. Next,

in a three-part sequence,

the motif is first

taken over the bass, while

the strings and the woodwind

play in stretto a kind of

accompaniment motif; the

solo oboe and the violino piccolo

then take up the motif in

stretto, and this is

followed by a three-bar

transition This sequence is

repeated twice - one has the

impression that it could go

on forever -

only to break off abruptly

during second repeat at the

bass motiv. The beginning of

the stretto one was

expecting here becomes an

oboe cadenza,

while the three-part bass -

oboes - strings sequence is

brought once

more into prominence by

alternating chords in the

unexpected conclusion. The

third movement is a true

concerto movement with six

rondo-like tutti blocks; the

principal soloist is the

violin piccolo, seconded by

the first horn and the first

oboe. The second tutti is

somewhat remarkable in that

it is played pianissimo: in

movements of this kind one

expects every tutti section

to be

forte; it is permeated by

unusual oboe and violin

solos. The fourth solo

(violino piccolo and first

ripieno violin) falls apart

into an adagio

chord, then is set going

again by what seems to bc

deployment of the rondo

theme -the real tutti

sections follow four bars

later. Although this

movement has the character

of a finale, it is followed

in turn by a minuet with the

most varied trio

combinations. It

was quite customary at the

beginning of the eighteenth

century (eg. Handel’s

concerti grossi) to conclude

exciting or stormy concerti

with a soothing minuet, in

order to send the listener

away in a relaxed frame of

mind.

Brandenburg Concerto no. 2

shows a profuse

rhetorical conception. It

turns out to be a complex

musical dialogue, in which

inversions and other devices

are used. Time afte rtime,

there is an exchange of

parts between the outer

instruments. The

instruments’ idiomatic

language (the scoring of the

solo quartet isextreme: a

high natural trumpet, a

recorder, an oboe, and a

violin, almost a repertoire

of the different ways of

producing sound) achieves an

impression of imitation by

the transfer of specific

instrumental figures to

other instruments.

In the first movement there

is a number of purely

tutti motifs, and several

others that are only played

by the soloists. In that

manner alone dialogue

results. Bach failed to

specify any dynamics, which

shows that he expected the

dynamic relations usual at

the time: solo sections were

played piano, tuttis as a

rule forte. (This of course

is quite the opposite

ofpresent-day practice.) The

soloist did not need to

struggle against the tutti,

as he was not accompanied by

the body of the orchestra,

but rather conducted

a dialogue with them. The

challenging initial

statement from the tutti is

succeeded by the protests of

the solo instruments and the

tutti reaction. It is

important to note that in

these various assertions the

different parts are often

simultaneously differently

articulated. Sometimes

this is expressly noted by

Bach. Varying articulation

in the different

parts results in a more

varied overall sound, with

the characters of the

individual instruments

becoming more distinct. Bach

obviously also expects

differing articulation when

a figure appears several

times, since the figure then

has an altered meaning in

the rhetorical context.

Analogy in the modern sense

is non-existent in Baroque

music, on account of its

similarity to conversation.

The second movement has a

double emotional

personality, one side coming

from the bass, the other

from the solo instruments.

The andante marking refers

primarily to the bass, which

proceeds in continuous

quavers that are to be

played at a steady pace.

Bach sets this ostinato

uniformity as a

counterweight to the strong

expressiveness of the three

upper parts.

The third movement begins

with a trumpet solo, which

runs contrary to the

tradition of the Baroque

concerto movement and of

Baroque rhetoric, for the

statement that opens the

movement is normally made by

the tutti and then

questioned by the solo.

Here, the preceding movement

leads directly into this

solo, which is an answer to

the last figure of the

second movement; therefore

there can be no pause

between these two movements.

The tutti just plays an

orchestral continuo here:

accompaniment, and the

thematic events, are

developed by the soloists

and the bass alone. In terms

of the concerto’s dramatic

layout, that means that the

entire finale is an

enumerated acceptance of the

challange

of the first movement.

In

the Brandenburg Concerto no.

4 the marking flauti d’echo

poses something of a puzzle

at first sight. High octave

flutes were occasionally

used, but

these have much louder

effect than ordinary

recorders, so that the

orchestra would then be the

“echo”. Bach surely meant

normal recorders. In the

first rnovement the roles of

the concertino are clearly

given out to the group of

soloists: the violin is the

main soloist, seconded by

the pair of recorders which

are also brought to the fore

again later in a lyrical

solo section (bars l57-185

and 285-311). The echo

effect in the second

movement may have heen so

important for Bach that he

included it in the title of

the concerto. The idea of

the echo here is a rapid

interruption of the melody,

which would proceed

continuously but for these

echo insertions. The echos

are at

those points where one ought

to write in a comma; they

force one to listen

attentively. The effect

which Bach seems to have

intended can only be

achieved if the flutes are

played from an adjoining

room. At points where they

are independent, as in bar

40, the orchestra must play

more quietly to balance the

sound. The andante marking

of the second movement seems

to refer to the tempo here,

and not to an “andante”

character of the whole

movement. The slow movement

should, then, receive a

gradual acceleration; the

paired quavers are not

played steadily here. A

fundamental feature of this

movement is the perfect

symmetrical arrangement,

which is comparable with the

architecture of a Baroque

palace, and which Bach uses

time and time again in his

major works. Around a

central section (bars 28-45)

are grouped four outer

sections. by

way of framing: of these,

the first and fifth only

differ in the interchanging

of the outer parts. The

second and fourth

sections correspond too,

with the difference that the

echoes in the 4th section

have a compressed effect. In

the central section there is

new material and a new

dialogue in that the

recorders voice soloistic

complaints here. In

the fifth

section the theme is in the

hass,

and the echoes of the

symmetrically matching first

section

are omitted: they would not

make sense in the repeat,

since the effect would no

longer be new. For

interpretation it is most

important to recognise this

symmetry - one would play

the piece difierently if the

sections were just

arranged in a row.

Although the third movement

is to be played directly

after the

second, without a

break, the recorder players

have time to return to their

places, since they do

not come in until bar

23. In this movement the

entire thematic material is

derived from the first four

bars.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

Translation:

Clive R. Williams

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|