|

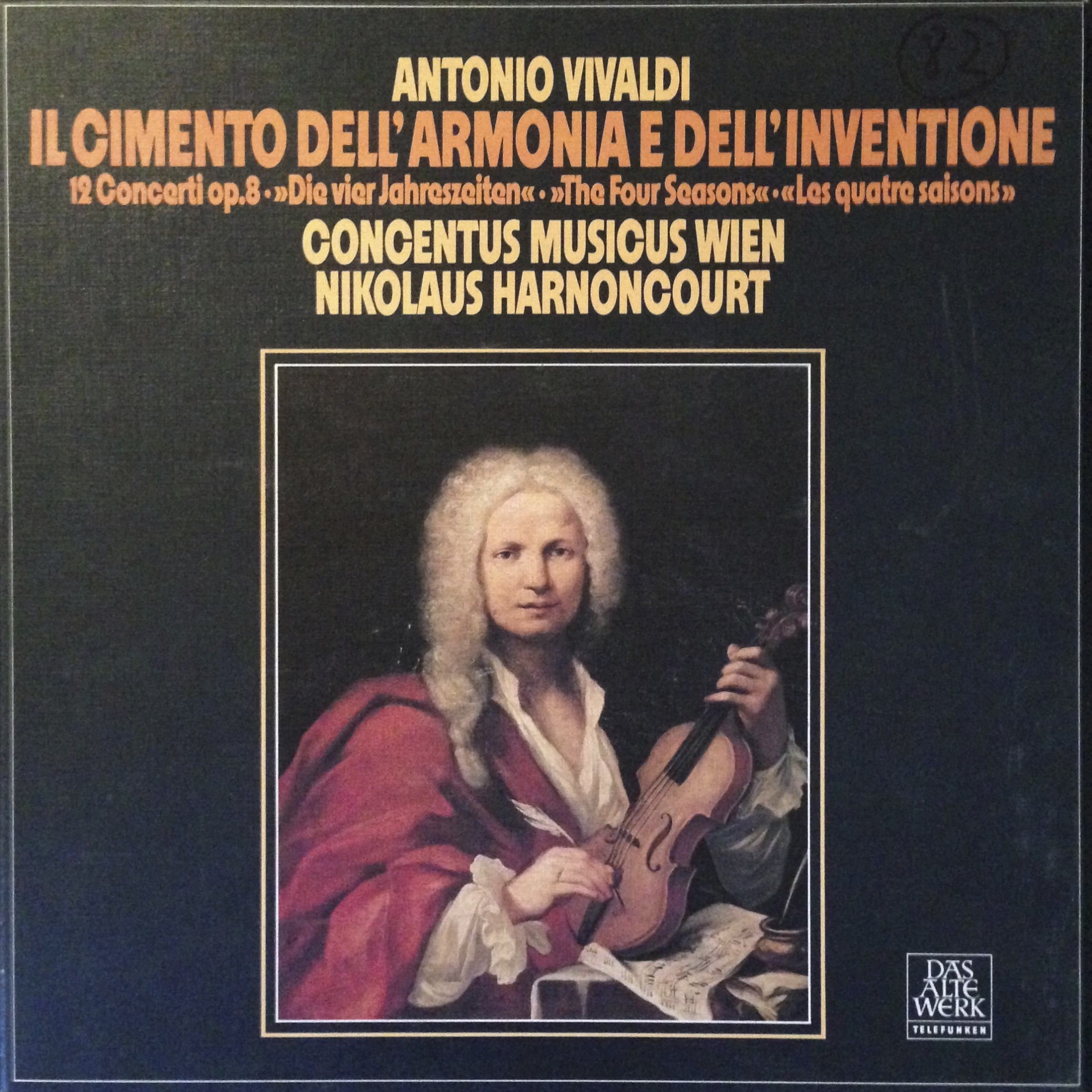

2 LP -

6.35386 EK - (p) 1977

|

|

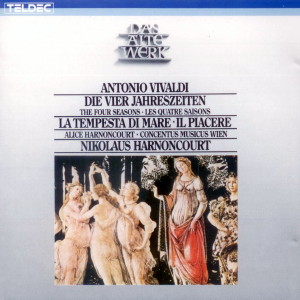

| 1 CD -

8.42985 ZK - (c) 1984 |

|

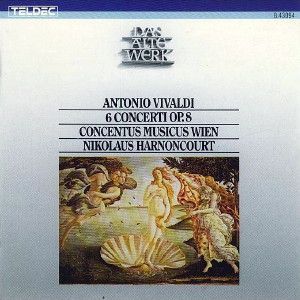

| 1 CD -

8.43094 ZK - (c) 1984 |

|

| Antonio Vivaldi

(1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Il Cimento dell'Armonia e

dell'Inventione, Op. 8

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Concerto I E-dur "La

Primavera" (F. I/22)

|

|

8' 15" |

A1 |

- Allegro

|

3' 08" |

|

|

| - Largo |

1' 53" |

|

|

| - Danza Pastorale: Allegro |

3' 14" |

|

|

| Concerto II g-moll "L'Estate"

(F. I/23) |

|

10' 51" |

A2 |

- Languidezza per il Caldo:

Allegro non molto

|

5' 41" |

|

|

- Adagio - Presto

|

2' 20" |

|

|

| - Tempo impetuoso d'Estate:

Presto |

2' 50" |

|

|

| Concerto III F-dur

"L'Autunno" (F. I/24) |

|

9' 31" |

A3 |

- Ballo e canto de'

Villanelli: Allegro

|

4' 07" |

|

|

- Dormienti ubriachi: Adagio

|

2' 38" |

|

|

- La Caccia: Allegro

|

2' 46" |

|

|

| Concerto IV f-moll

"L'Inverno" (F. I/25) |

|

7' 56" |

B1 |

- Allegro non molto

|

3' 30"

|

|

|

| - Largo |

1' 17" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

3' 09" |

|

|

| Concerto V Es-dur "La

Tempesta di Mare" (F. I/26) |

|

8' 38" |

B2 |

- Presto

|

2' 38"

|

|

|

| - Largo |

2' 30" |

|

|

- Presto

|

3' 30" |

|

|

| Concerto VI C-dur "Il

Piacere" (F. I/27) |

|

7' 31" |

B3 |

| - Allegro |

2' 43" |

|

|

| - Largo |

2' 08" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 40" |

|

|

Concerto VII d-moll (F. I/28)

|

|

7' 26" |

C1 |

| - Allegro |

2' 37" |

|

|

| - Largo |

1' 51" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 58" |

|

|

Concerto VIII g-moll (F.

I/16)

|

|

8' 47" |

C2 |

| - Allegro |

2' 37" |

|

|

| - Largo |

2' 14" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

3' 56" |

|

|

Concerto IX d-moll (F. I/1) *

|

|

7' 24" |

C3 |

| - Allegro |

2' 58" |

|

|

| - Largo |

1' 57" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 29" |

|

|

Concerto X B-dur "La Caccia"

(F. I/29)

|

|

7' 44" |

D1 |

| - Allegro |

2' 58" |

|

|

| - Adagio |

2' 26" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 20" |

|

|

Concerto XI D-dur (F. I/30)

|

|

11' 06" |

D2 |

| - Allegro |

4' 25" |

|

|

| - Largo |

1' 54" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

4' 47" |

|

|

Concerto XII C-dur (F. I/31)

*

|

|

9' 02" |

D3 |

| - Allegro |

3' 17" |

|

|

| - Largo |

2' 26" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

3' 19" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alice Harnoncourt,

Violino principale

|

|

Jürg Schaeftlein,

Oboe *

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS WIEN (mit

Originainstrumenten)

|

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

-

Alison Bury, Violine (1-4)

|

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

|

| -

Wilhelm Mergl, Violine |

-

Josef de Sordi, Viola |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Violoncello |

|

| -

Richard Motz, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Ingrid Seifert, Violine |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Organo /

Cembalo |

|

-

Veronika Schmidt, Violine (5-6)

|

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus Harnoncourt,

Leitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Casino Zögernitz,

Vienna (Austria) - ottobre 1976 e marzo

1977 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Heinrich

Weritz

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 8.42985 ZK - (1 cd) -

53' 42" - (c) 1984 - (Concerti I-VI)

Teldec "Das Alte Werk" -

8.43094 ZK - (1 cd) - 52' 26" - (c) 1984

- (Concerti VII-XII)

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Telefunken "Das

Alte Werk" - 6.35386 EK - (2

lp) - 53'

42"

+ 52' 26" - (p) 1977

|

|

|

Notes

|

Vivaldi composed the

majority of his numerous concertos for

his own ensemble, the famous orchestra

of the Ospedale della Pietà

in Venice In 1704 he began to teach

the violin at this institution, and

from c. 1714 onwards held the

post of “maestro dei concerti". One of

several Venetian institutions

of its kind, the Ospedale was

devoted to the care of orèhaned and

abandoned gorls, who, if they showed

some aètitude, were given a musical

education. The regular performances

of concertos during services on

Sundays and holidays constituted one

of the city's principal attractions,

and travellers were quick to lavish

praise on the playing of the girls.

For example, in 1668 Peter Tostalgo

noted: "There are convents in Venice

whose inmates sing and play

the organ and various other

instrrrments so beautifully that

nowhere in the world will you find

music that is so harmonious and

sweet."

When Vivaldi included works from this

repertory in his

printed editions, he

tended to subject them to

radical revision. A comparison of the

two versions reveals that, in order to

make them commercially viable, the

printed editions usually contained a

considerable number of technical

simplifications. The Opus VIII

concertos, Il cimento dell'armonia

e dell'inventione (the title,

roughly translated, signifies “daring

experiments with harmony and

invention”), were not, it seems,

written especially for publication.

Not even the pieces that constitute

"The Four Seasons”, the

centrepiece of the collection, were

new works.

The source used in this

performance is the edition published

in Paris by Le Clerc et Me Boivin. We

consider this to be particularly

reliable in view of the fact that it

appeared immediately after the first

edition: it was carefully edited and

thus contains virtually no mistakes.

Vivaldi rendered into music the

sonnets on which “The Four Seasons"

are based, thus imparting to the work

its detailed programmatic character.

This is underlined by the fact that

letters in the parts correspond to

certain lines in the sonnets.

In the first concerto, La

primavera, the arrival of spring

is depicted in a rather theatrical

manner. The first movement, a rondo,

is a dance in the style of a bourrée

that is repeatedly interrupted by

naturalistic passages. In the slow

movement three different kinds of

tone-painting are applied

simultaneously: the calm melody of the

solo violin depicts the innocent

slumber of the shepherds, the ripieno

violins render into music the pleasant

sound of leaves rustling in the wind,

and, in a rather direct manner, the

viola imitates the barking of dogs.

The final movement with its 12/8

siciliano rhythms is a delightful

rural tableau in the style of the

baroque era peopled with dancing

shepherds and nymphs.

In L'estate (Summer),

extremely soft pianissirno dynamics

characterize breathless languor and

the heat of surnrner the slightest

movement results in complete

exhaustion. The image of oppressive

heat, which is repeated several times

in the style of a rondo (bars 52-59

and 110/116), is later recalled in L'inverno

(Winter), where it evokes the warm

scirocco wind. The cuckoo (from bar 31

onwards) is heard amidst lively

repeated semiquavers that represent a

throng of chattering birds. The

complaint of the peasant makes use of

chromaticism, a classical device of

musical rhetoric: in the slow

descending scales in the bass it

depicts resigntion, and in the solo

violin the passionate weeping and

sobbing characteristic of the south.

We hear the apprehensive boy (bars 153

and 154), and then the storm breaks

out. In the slow movement, which

depicts his attempt to overcome his

anxiety and regain his composure, the

melodic line is repeatedly interrupted

by presto passages representing

thunder, lightning and swarms of

insects, The last movement is a

musical evocation of a severe summer

thunderstorm.

L'autunno (Autumn) begins with

a merry peasants’ dancing song in

which the solo violin assumes the role

of lead singer repeating and

embellishing the music of the chorus.

Vivaldi takes great delight in

depicting a drunkard in various states

of inebriation, though this is

repeatedly interrupted by the communal

singing. The movement ends abruptly

with the dancing song with which it

began, though now, as the wine begins

to take effect, it is played faster.

In the slow movement, which evokes the

image of pleasant slumber, Vlvaldi

calls for mutes and arpeggios on the

harpsichord. The third movement is

devoted to a musical description of

the hunt.

In L'inverno (Winter) the

freezing wintry cold is depicted by

sharp bow vibrato, piercing

dissonances, and, in the first violin,

by two-finger vibrato, a kind of

microtonal trill. Particularly complex

and subtle, the slow movement shows

man happy and content in the safety of

his house, where he is warmed by the

fire and protected from the wintry

showers. The cello (molto forte)

depicts a sudden downpour, and rather

loud pizzicato in the upper strings

the water dripping down from the

eaves. Almost obscured by all this and

none the less audible, the delightful

melody of the person sitting hy the

fireside is accompanied by viola (pianissimo),

organ and bass (piano). In the

last movement Vivaldi stipulates that

the slurs in the violins (arcate

lunghe) which depict the

slippery ice must not be divided. This

indication was of some importance: in

general, long slurs merely indicated

that slurring was required, and

usually this meant short slurs, Fear

is once more depicted by intensive bow

vibrato After the drama on the ice,

which ends with a fall and the ice

breaking up, we hear the warm scirocco

wind leaving its winter quarters (bars

102-120). Here Vivaldi makes use of

the image of oppressive heat from L'estate

(Summer), and this reminds us of the

cyclic pattern of the whole work.

La tempesta di mare depicts the

stormy sea and waves that roll in from

afar, syncopated breakers, as it were,

whose whirling spume and foaming

crests (from bar 53 onwards) tower

ever higher and closer (from bar 61

onwards), The description obviously

continues in the second rrrovement.

There is a moment of tranquillity, and

the waves begin to subside. However,

quiet undulation continues to be

clearly audible in the unison triads

of the tutti. In the third movement

bizarre general pauses that retard the

flow of the music and unusual and

cleverly concealed changes of metre

reflect the musical daring announced

in the collective title.

At the beginning of Il piacere

rejoicing and exultation are portrayed

by means of syncopations and

embellished leaps of a fifth. The slow

movement with its 12/8 siciliano

rhythm is evidently a depiction of

rural life: in the baroque era

pastoral scenes were always symbolic

of harmony and of pure and innocent

joy. However, in the third movement

the rejoicing has acquired a comical

and somewhat derisory character. In

the tutti large leaps of an octave, a

tenth, a twelfth and more lead to

suspensions, striking and mocking

gestures that, in the form of a

dialogue, stand in marked contrast to

the solo part.

The structure of Concerto No. 7 is

quite different. The same material is

employed in the tutti and solo

passages, and thus the soloist merely

comments on the motto theme first

played by the orchestra. The movement

depicts and contrasts numerous

affections of a passionate, tender,

active and passive kind. In the slow

movement the soloist embelhshes the

repeats in an improvisatory manner to

the accompagniment of arpeggios played

alternately by the first and second

violins. The last movement is rather

witty and sometines verges on

slapstick.

The influence of the commedia

dell'arte is clearly apparent in

Concerto No. 8. The solo violin is

given motifs of its own (which are

distinct from those of the tutti

passages), though these themes are

frequently incomplete. The initial

motif finally continues on its own.

Although the tutti passages are based

on the material of the first tutti,

they are always varied in a witty

manner. The second movement, which is

in the style of sixteenth-century

vocal polyphony; comes an something of

a surprise. A secular movement is

followed by a sacred one, just at the

carnival season is followed by Lent

(which is hinted at by sorrowful

chromaticism in the bass). The finale

is a whirling popular dance with

bizarre chords and rather eccentric

violin solos.

In Concerto No. 9 at stubborn

syncopated motif supported by the

quavers of et walking bass is answered

and challanged by two lamento bars,

which consist of a rhapsodic and

sorrowful chromatic motif. The first

solo passage is a free adaptation of

the syncopated motif of the opening

tutti. The tutti passages that

separate the cheerful and witty solo

sections always end with the lamento.

The slow movement, which is for oboe

and basso continuo, continues to dwell

on the sad and elegiac mood of the

first movement. The finale, as in so

many of Vivaldi's concertos. is based

on a lively popular dance. The unusual

rhythm (the fact that 3/2 and 2/2

alternate in an irregular manner

becomes apparent from the metrical

structure, and not from the notation),

the voice leading, and the soloist's

embellishments are all reminiscent of

oriental music. Venice maintained

close links with the Countries of the

eastern Mediterranean for centuries,

and thus it is not surprising that

Venetian composers were often

influenced by Mediterranean folk

music.

The vigorous 3/4 thermes which imitate

the horn in the next concerto. La

caccia, describe jolly huntsmen

riding out into the countryside in

pursuit of their quarry. The hunters

and the hunted are depicted by the

solo violin's triplet runs and horn

motifs. This game is repeated four

times (though on the second occasion

the animal is cornered and killed).

The second movement does not seem to

have anything to do with this subject,

though its striking rests impart a

special and almost hesitant character

to the musical dialogue. The last

movement again depicts a hunt. As in

the first movement, there are several

episodes (which are separated by tutti

passages) and these seem to depict the

reactions of various animals. The

first shows one of them simply running

away; and in the second another one

leaps up and then crawls along. The

large leaps in the third episode

culminate in an animal's attempt to

escape, and its melancholy end.

Concerto no. 11, which begins with a

four-part fugato, is a brilliant

compendium of contemporary stylistic

possibilities The contrapuntal

introduction is interrupted once by a

motif that whirls along nimbly in the

style of Neapolitan folk music for

mandolins, and then by sentimental

syncopations. In this concerto Vivaldi

revels in some impressionist sounds

which only becorrre audible in

performance and cannot be deduced from

the individual parts. The slow

movement is also based on such magical

images: with the help of bow vibrato

the upper strings create a texture

from which the solo violin emerges

like an upper partial that becomes

more and more audible. The finale

begins with a fugato, as in the first

movement; and the first tutti ends

abruptly with an incisive dotted motif

repeated four times and some soft

scales. With the exception of the

fugato sections, this movement is

another example of the oriental

influence that was omnipresent in

Venice.

The first movement of Concerto No. 12

is unmistakably rustic in character.

Vivaldi seems to have been inspired to

write this very rural piece by the

sound of the oboe, and by a plethora

of ideas derived from folk music. The

motifs of the solo oboe, which are

quite different from those of the

strings, are cantabile and elegant, so

that we seem to be hearing a

conversation between a master and his

servant. In the slow section the

repeats are embellished in an

improvisatory rnanner. The last

movement is once again in the style of

a rustic dance.

Nikolaus

Harnoncort

Translation:

Alfred Clayton

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|