|

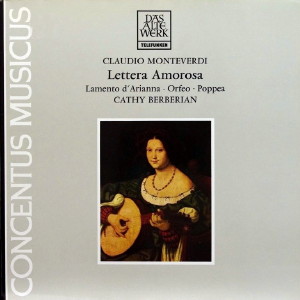

1 LP -

6.41930 AW - (p) 1975

|

|

| 1 CD -

8.43635 ZS - (c) 1987 |

|

| Claudio

Monteverdi (1567-1643) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lettera amorosa - a voce sola in genere

rappresentativo, 1619 |

7' 09" |

|

A1 |

| Con che soavità - concerto a una voce e

istromenti, 1619 |

4' 26" |

|

A2 |

| Lamento d'Arianna - (Ariana) 1613 |

12' 49" |

|

A3 |

| "L'Orfeo" - Mira, deh mira,

Orfeo... In un fiorito prato |

6' 36" |

|

B1 |

| - 2. Akt, Pastore

secondo, Messaggera, Pastore primo,

Orfeo |

|

|

|

"L'Incoronazione di Poppea" -

Disprezzata Regina

|

4' 23"

|

|

B2 |

| - 1. Akt, V. Szene,

Ottavia |

|

|

|

| "L'Incoronazione di Poppea" -

Tu che dagli avi miei... Maestade, che

prega |

6' 16" |

|

B3 |

| - 2. Akt, IX. Szene,

Ottavia, Ottone |

|

|

|

| "L'Incoronazione di Poppea" -

A Dio Roma |

3' 56" |

|

B4 |

| - 3. Akt, VI. Szene,

Ottavia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cathy

Berberian, Mezzosopran |

|

|

|

|

|

| CONCENTUS

MUSICUS WIEN (1-3) |

L'Orfeo

|

|

| -

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo |

Extracted

from the production of

1969: |

|

| -

Johann Sonnleitner, Cembalo (2) |

Telefunken

SKH 21/1-3 |

|

| -

Toyohiko Satoh, Chitarrone (2) |

|

|

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine (2,3)

|

L'Incoronazione

di Poppea |

|

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine (2,3)

|

Extracted from the

production of 1974: |

|

| -

Kurt Theiner, Viola (2,3) |

Telefunken

6.35247 HD |

|

| -

Josef de Sordi, Tenorbratsche (3) |

|

|

| -

Elli Kubizek, Viola da Gamba (2) |

|

|

| -

Jonathan Cathie, Viola da Gamba

(2) |

|

|

| -

Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Violoncello

(2,3) |

|

|

| -

Eduard Hruza, Violone (2,3) |

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| 1975

(A1-A3) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

Teldec

"reference" - 8.43635 ZS - (1 cd) - 46'

21" - (c) 1987 - AAD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Telefunken "Das

Alte Werk" - 6.41930 AW

- (1 lp) - 46'

21"

- (p) 1975

|

|

|

Notes

|

The

presentation of early

dramatic music is fraught

with problems which scarcely

respond to general

solutions. On the one hand

within this music the

dramatic forms of the

recitative and aria, as well

as of orchestral treatment

of the Italian opera, are

not yet as fully developed

as in Mozart’s master works,

where this tradition is

super-elevated

and concluded. Nor are the

parts entirely through

composed, but expect the

singer to provide his own

arrangement with improvising

figures. On the other hand

the tradition of this older

vocalpractice has been lost

to both the singer and the

listener. However, a

singer’s basic renunciation

of his own arrangement would

not only impair the musical

dramatic impact, but also

adulterate the work.

Monteverdi’s musical,

artistic reasons for his

dramatic compositions were

similar to those which moved

Mozart to write “Figaro’s Hochzeit”

or Verdi “La Traviata": It

was not merely a matter of

musically illustrating a

plot; the object was

musically to depict human

beingswith their feelings

and wishes, with their

finest spiritual impulses.

Cathy Berberian is aware

that any attempt at

reconstruction of the

missing tradition would

amount to a bogus return to

history, a kind of pretence.

But her knowledge of the

general practices of that

era, the examples of which

produced in text books

cannot be transferred to

each and every piece, her

appreciation of the

repercussions of Monteverdi

and his intentions, combined

with an enormous feeling for

music and almost unlimited

vocal possibilities,

contribute towards a new

Monteverdi interpretation.

Thus a vocal style emerges

which is far removed from

the history-laden ecstasy of

early music, but full of

inner drama, derived from

the music itself. It is

above all the

intonation, which is

unconventional for early

music, the breadth of the

dynamic shades which are

derived from the spiritual

impulses of the persons in

the music rather than being

vested in the music.

Dramatic outbursts and the

almost “speaking

expression", such as in the

magnificent “Lamento

d’Arianna” are taken as much

for granted as the free

arrangement of the timing

when reading the “Love

Letter”. Improvised

coloraturas and trills are

consciously ecnomical, but

are applied with an unerring

sense for the appropriate

spots; not every long

sustained note can take an

embellishment, and many of

them are already through

composed.

The news of the death of

Euridice, brought to Orpheus

by the messenger, is quite

rightly regarded as the

musically most important

scene in “Orfeo” because the

emotions of the messenger

and Orpheus confront each

other. The basic idea of the

whole opera culminates in

this excerpt. Cathy

Berberian’s vocal expressive

range reaches at this point

a richness of timbre which

only fifteen or twenty years

ago would have been

criticised as completely

un-Baroque. And yet the

essence of this touching

scene could scarcely be more

effectively reproduced than

with the almost toneless,

and yet in its hardness

fully articulated sentence

“La tua diletta sposa é

morta” (Thy beloved wife is

dead). Thus Monteverdi’s

music has neither an

academic nor historising

effect, nor is a later

operatic style forced upon

it; because of an

appreciation of its problems

it is dramatically vivid

music with a direct impact.

Gerhard

Schuhmacker

Translation:

Frederick A. Bishop

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|