|

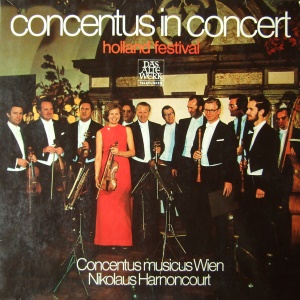

1 LP -

SAW 9626-M - (p) 1974

|

|

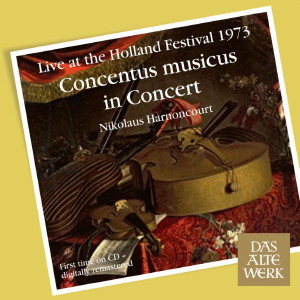

| 1 CD -

2564 66211-9 - (c) 2012 |

|

concentus in concert -

holland festival

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio Vivaldi

(1678-1741) |

|

|

|

| Concerto B-dur op.10,2 "La

Notte" P. 342 |

|

8' 35" |

A1 |

- Largo

|

1' 14" |

|

|

| - Fantasmi: Presto - Largo -

Andante |

3' 03" |

|

|

| - Il Sonno: Largo |

1' 39" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 42" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Georg Friedrich Händel

(1685-1759) |

|

|

|

Concerto Nr. 3 (1) g-moll für

Oboe, Streicher und B.c., Hwv 287

|

|

8' 45" |

A2 |

- Grave

|

2' 32" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

1' 56" |

|

|

| - Sarabande: Largo |

2' 13" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

2' 06" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Marin Marais (1656-1728) |

|

|

|

Suite aus "Alcyone"

|

|

17' 30" |

B |

| - 1er Air: Gravement et

piqué |

2' 07" |

|

|

| - 2ème Air: Sarabande |

2' 14" |

|

|

| - Gigue |

1' 22" |

|

|

| - Menuet |

1' 40" |

|

|

| - Air des Matelots I et II |

0' 45" |

|

|

| - Air des Matelots:

Tambourin |

0' 38" |

|

|

| - Chaconne |

7' 10" |

|

|

| - Tambourin I et II |

1' 42" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Concentus

Musicus Wien |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Lutherse Kerk,

Den Haag (Olanda) - 26 giugno 1973 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 2564 66211-9 - (1 cd)

- 73' 37" - (c) 2012 - ADD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Telefunken "Das

Alte Werk" - SAW 9626-M

- (1 lp) - 34'

50"

- (p) 1974

|

|

|

Notes

|

When in 1953 the

twenty-flve-year-old celllst Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, together with some of his

colleagues from the Vienna Symphony

Orchestra, formed an ensemble

specialising in early music played on

period instruments, no-one dreamt that

a new era of authentic musical sound

was opening up. After a four-year

pcriod of preparation, Harnoncourt

gave an initial concert, which was

followed by annual cycles and tours

abroad. In 1963 the Brandenburg

Concertos were introduced into the

programme. But it was the gramophone

recording that played a decisive role

in communicating this new concept of

what early music sounded like, and in

particular its

interpretation in conformity with

historical performance practice. The

medium's success could be measured by

the increased following for this

freshly revived performance practice.

The Concentus musicns Wien now

effectively became a recording

ensemble.

The fact that, besides meeting

ever-growing recording demands, the

members of the Concentus musicus Wren

continued to play on modern

instruments for opera and concert

performances at first prevented the

ensemble from establishing itself

fully on the concert circuit. In 1968

Harnoncourt became more heavily

involved than before in the concert

series of different cities. in spite

of reservations about the lack of

suitable halls. For Harnoncourt, the

extraordinary success of this

enterprise was proof that the effects

of launching a career primarily with

recordings were surprisengly

far-reaching, and that music-lovers

were just as keen to experience the

ensemble in the concert hall in a live

performance as on record.

There is one very good reason for

this: at these concerts the listener

discovers that the Concentus musicus

ensemble is not just a touched-up

product of the recording studios where

any sub-stadard passages are re-done,

or inaccurate intonation from the

rather temperamental period wind

instruments smoothed out, but one that

more than confidently holds its own in

the traditional concert world - it

shines there. It is not, therefore,

merely a sterile reconstruction of an

archaic concept of sound. Instead we

receive the direct impact of a lively

performance by present-day musicians

of vitality and temperament in which

they convey a concept of musical sound

that we have been able to reproduce

from historical models - albeit with

the feelings of a musician of today.

The popularity of the Concentus

musicus on the public concert platform

also goes to prove that this group has

succeded in avoiding that academic air

otherwise associated with the esoteric

specialist. Not only has it got away

from the mechanical srape-scrape

jocularity of traditional "baroque"

music-making, but it also knows how to

keep free from mannerism, from the

evils of an artificially reconstructed

art, a manipulated appropriation of

music from the past. It goes without

saying that only highly qualified

musicians could ever attempt this

confrontation - i. e. modern

instrumentalists vis-a-vis the musical

ideals of sound of a bygone era. They

show - on the concert platform clearly

and indisputably - just how thrilling

their playing can be, how lucidly

Harnoncourt, not from the conductor's

rostrum but from the 'cellist's desk,

can demonstrate the music of

yesterday, freed from the false

conventions of the nineteenth century.

Free too from any hint of mass

production in respect of style and

timbre, free from puristic bias and

academic blinkers, always flexible in

respect of the uniqueness of an actual

performance - at a public concert so

refreshing and at the same time

illuminating, and at a studio

recording session allowing the

livelines to be pressed into the

grooves with the music. And this is a

true of their Monteverdi as of their

Mozart, to name but two corner-stones

of the Concentus musicus repertoire.

Monteverdi's music, a crucial part of

Harnoncourt's work, is given in

addition to its authentic "soynd

picture" a performing style, as a

result of Harnoncourt's serupulous

research, translated for us so that

the "language" of the "talking"

intervals and musical devices becomes

intelligible and meaningful even to

the modern listener with no knowledge

of the ancient principles of musical

rhetoric. And this so direct and

convincingly that public performances

like that of Monteverdi's opera "The

Return of Odysseus" at the Vienna

Festival could turn out to be as much

a success with the audience as any

popular Verdi opera. Mozart is

likewise treated to a more authentic

interpretation than stereotyped

concert life usually affords it: truer

in respect of tonal balance and

colour, of phrasing, and, in

particular, of its Mozartian rhythms,

which, freely breathing and

improvisational, combine with the

melodic accent.

At a live concert performance the

listener is made to realize that the

members of the Concentus musicus

regard the irretrievability of each

moment, the fact that there is no

chance to repeat a passage, as

something positive, which makes for a

much more intense awareness of the

other partners and of the hall itself.

----------

In

baroque times music was much more an

immediate, intelligible “language”

than we can conceive of today. The

“musical speech“ or formulas of

communication followed certain rules

known, at least, to the musicians.

Everything was governed by a distinct

musical rhetoric embracing details

such as characteristic motifs of

intervals. We have only to think of

the association of moods with modes

and keys for a very marked example, or

the "oratorical“, in the double sense

of the term, or what Mattheson called

"Klangrede" (musical speech). Today,

we approach this music from a more or

less purely aesthetic aspect, without

really “understanding” the language.

Significantly, too, it is realized to

a much greater extent in the music of

J. S. Bach than, in say, that of

Vivaldi that certain musical "signs"

possess concrete meanings or

extra-musical associations exactly

“translatable". And this despite the

latter’s frequent use of such sound

patterns. In Vivaldi’s music we find,

rather, a direct conversion into

musical language of impressions from

Nature, or character traits - a kind

of programme music, of which the

French were very fond too. As,

however, the term “programme music“ in

its nineteenth century connotation has

become somewhat suspect to us, it

needs to be employed here with

caution.

"La Notte“ for example, Vivaldi used

as a title for two compositions, once

for a flute concerto and then for a

bassoon concerto. The flute concerto

contains headings with exact

specifications. Vivaldi, however,

appears rather to model his music on

the idea than to copy it - although

one could not go so far as to use the

term "Empfindung" for it in the sense

one uses it with Beethoven. The first

movement of Opus 10 No. 2 in G minor

is entitled "Fantasmi", but conjures

up troubled thoughts rather than

actual phantoms: scales are wound

together canonically or in thirds,

syncopations and rapid semiquavers

convey a mood of unrest. A calming

flute melody is contrasted with

triplets on the bassoon. The second

movement, "ll Sonno", does not produce

an altogether peaceful "sleep" either:

subtle chromaticism, freely

interpolated suspensions and

dissonances which remain unresolved

over long stretches offer a sharp

contrast to the gentle close: the

night wins through. the dreams vanish.

The influence of the ltalian style on

Handel's work right up to the last

should not be underestimated, any more

than should the effect of Handel's own

personal style on his early "Italian"

compositions. Thus in the Oboe

Concerto in G minor we find both the

concertante principles of ltalian

baroque and the sweeping

improvisational element, the robust

musicality of Handel himself,

represented with equal conviction.

With Handel's music we have not only a

"language" but the charm of an

individual "accent" too.

Marais, a fine bass-viol player, was,

after his teacher Lully, the most

famous of the French baroque

musicians. He was probably the first

composer to try to produce natural

effects with musical media. It is said

that, in order to find novel effects

for a storm scene in his crpera

"Alcyone", written for the Parisian in

1706, he made a special journey to the

coast. Thus, what in appearance is a

conventional suite is, in fact, also a

depiction of natural phenomena, such

as we can find being constantly tried

out in the music of the succeeding

centuries.

W. E. v.

Lewinski (1973)

Translation: Avril Watts

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|