|

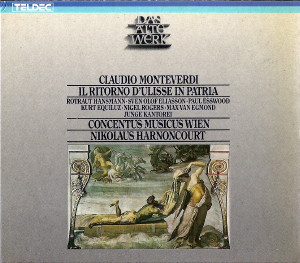

4 LP -

SKB-T 23/1-4 - (p) 1971

|

|

| 3 CD -

8.35024 ZB - (c) 1986 |

|

Claudio

Monteverdi (1567-1643)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Il Ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prologo

- L'Humana fragilità, Tempo, Fortuna,

Amore

|

|

9' 12" |

A1 |

Atto

primo

|

|

66' 44" |

|

| - Scena I: Reggia. Penelope,

Ericlea |

11' 07" |

|

A2 |

| - Scena II: Melanto, Eurimaco |

10' 32" |

|

B1 |

| - Scena V: Nettuno sorge dal

mare, e Giove |

7' 26" |

|

B2 |

| - Scena VI: Coro di Feaci in

nave, poi Nettuno |

2' 16" |

|

B3 |

| - Scena VII: Ulisse si risveglia |

4' 48" |

|

C1 |

| - Scena VIII: Minerva in abito

da pastorello e detto. Ulisse |

12' 55" |

|

C2 |

| - Scena IX: Minerva e Ulisse |

2' 12" |

|

C3 |

| - Scena X: Reggia. Penelope,

Melanto |

9' 00" |

|

C4 |

| - Scena XI: Eumete solo |

1' 45" |

|

D1 |

| - Scena XII: Iro et Eumete |

1' 50" |

|

D2 |

| - Scena XIII: Eumete, poi Ulisse

in sembianza di vecchio |

3' 33" |

|

D3 |

| Atto secondo |

|

71' 08" |

|

| - Scena I: Reggia. Penelope,

Melanto |

2' 46" |

|

D4 |

| - Scena II: Reggia. Penelope,

Melanto |

5' 04" |

|

D5 |

| - Scena III: Reggia. Penelope,

Melanto |

7' 26" |

|

D6 |

| - Scena IV: Reggia. Penelope,

Melanto |

3' 00" |

|

D7 |

- Scena V: Antinoo, Anfinomo,

Pisandro, Eurimaco, Penelope. Balletto

|

10' 00" |

|

E1 |

- Scena VII: Eumete e Penelope

|

1' 13" |

|

E2 |

- Scena VIII: Antinoo, Anfinomo,

Pisandro, Eurimaco

|

6' 19" |

|

E3 |

- Scena IX: Boschereccia.

Ulisse, poi Minerva in abito maestro

|

3' 42" |

|

E4 |

- Scena X: Eumete, Ulisse

|

2' 02" |

|

E5 |

- Scena XI: Telemaco, Penelope

|

5' 16" |

|

E6 |

- Scena XII: Antinoo, Eumete,

Iro, Ulisse, Telemaco, Penelope, Pisandro,

Anfinomo

|

24' 20" |

|

F |

| Atto terzo |

|

46' 32" |

|

| - Scena I: Iro solo |

6' 23" |

|

G1 |

| - Scena III: Reggia. Melanto e

Penelope |

3' 01" |

|

G2 |

- Scena IV: Eumete e detti

|

2' 51" |

|

G3 |

- Scena V: Telemaco e detti

|

3' 08" |

|

G4 |

- Scena VI: Marittima, Minerva e

Giunone

|

3' 32" |

|

G5 |

- Scena VII: Giunone, Giove,

Nettuno, Minerva, Coro e celesti

|

7' 38" |

|

G6 |

| - Scena VIII: Ericlea solo |

4' 28" |

|

H1 |

| - Scena IX: Penelope, Telemaco,

Eumete |

0' 53" |

|

H2 |

- Scena X: Sopraggiunse Ulisse

in sua forma e detti

|

11' 34" |

|

H3 |

|

|

|

|

| Sven

Olof Eliasson, L'Humana

fragilità, Ulisse |

Kai

Hansen, Telemaco |

|

Walker

Wyatt, Tempo, Antinoo

|

Kurt

Equiluz, Pissandro |

|

Margaret

Baker-Genovesi, Fortuna,

Giunone, Melanto

|

Paul

Esswood, Anfinomo |

|

| Rotraud

Hansmann, Amore, Minerva |

Nigel

Rogers, Eurimaco |

|

| Ladislaus

Anderko, Giove |

Max

van Egmond, Eumete |

|

| Nikolaus

Simkowsky, Nettuno |

Murray

Dickie, Iro |

|

| Norma

Lerer, Penelope |

Anne-Marie

Mühle, Ericlea |

|

|

|

| Junge Kantorei,

Coro in cielo e marittimo /

Joachim Martini, Einstudierung |

|

|

|

Concentus Musicus

Wien & Instrumentalsolisten

|

|

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine

|

-

Andreas Wenth, Posaune |

|

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine

|

-

Otto Fleischmann, Dulzian |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Jürg Schaeftlein, Blockflöte,

Piffaro

|

|

| -

Wilhelm Mergl, Violine |

-

Leopold Stastny, Blockflöte |

|

| -

Josef de Sordi, Violine |

-

Elisabeth Harnoncourt, Blockflöte |

|

-

Kurt Theiner, Tenorbratsche

|

-

Paul Hailperin, Blockflöte,

Piffaro

|

|

| -

Hermann Höbarth, Violoncello und

Viola da Gamba |

|

|

| -

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

Continuo: |

|

| -

Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Tenorviola

und Viola da Gamba |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo,

Virginal, Orgel, Regal

|

|

| -

Fritz Geyerhofer, Violoncello |

-

Johann Sonnleitner, Cembalo,

Virginal, Orgel, Regal |

|

| -

Josef Spindler, Trompete |

-

Josef Wallnig, Cembalo,

Virginal, Orgel, Regal |

|

| -

Hans Pöttler, Posaune |

-

Eugen M. Dombois, Lauten,

Chitarrone |

|

| -

Karl Jeitler, Posaune |

-

Toyojiko Satoh, Lauten,

Chitarrone |

|

| -

Hans Pöttler, Posaune |

-

Erna Gruber, Harfe |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Musikalische

Einrichtung und Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Casino Zögernitz, Vienna

(Austria) - aprile / maggio / giugno

1971 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolf Erichson |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec "Das Alte Werk" -

8.35024 ZB - (3 cd) - 70' 04" + 54' 25"

+ 68' 12" - (c) 1986

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" -

SKB-T 23/1-4 - (4 lp) - 40' 40" + 54'

37" + 53' 04" + 43' 45" - (p) 1971

|

|

|

The

Homecoming of Odysseus

|

Three

operas by Monteverdi have

come down to us: “l’Orfeo”,

“il Ritorno d’Ulisse in

Patria” and “l’Incoronazione

di Poppea”. The first was

written in 1607, in Mantua,

and the last two in Venice

after 1640. In the

thirtythree intervening

years, the historical and

musical transition from the

renaissance to the baroque

period took place. It is

therefore not surprising

that the differences between

the first and the last two

of Monteverdi’s operas are

very great - they are in

fact much greater that one

would expect between works

of the same category by one

and the same composer.

“L`Orfeo", which counts as

the first authentic opera,

was written shortly after

the invention of the

dramatic recitative, which

is identified

musicologically with the

invention of opera itself.

In this work Monteverdi has

combined the long

established pastoral

madrigals with the new

recitative style into a

remarkable formal mixture of

the traditional and the

modern; it was the

beginning, and at the same

time the first great

culmination, of this new

musical form. Here he could

use the sumptuous

renaissance orchestra of the

“intermezzi” for the last

time, thereby exactly

stipulating many details,

from the instrumentation

right clown to the

ornaments. As may be

imagined, this left very

little room for

improvisation or any other

freedom of interpretation.

Unfortunately, the dramatic

works written by Monteverdi

between L’Orfeo and Il

Ritorno d’Ulisse are no

longer in existence; only

the “Lamento d’Ariana” (a

short operatic scene which

Monteverdi published in two

different madrigal versions)

and the short “Combattimento

di Tancredi e Clorinda” give

us some idea of the

development of Monteverdi’s

dramatic style. At the end

of this continuous evolution

stand the two later operas

“Ulisse” and “Poppea”. Here,

the concentrations of

musical substance which, in

“l`Orfeo”, were still in the

madrigals, are dissolved or,

rather, displaced.

Monteverdi now desires to

achieve the best possible

effect of the words; the

music may never draw the

attention away from this,

never be an end in itself;

interpreting and moving the

action forwards, it must

underline and intensify the

meaning of the words, so

that the listener, without

becoming aware of it, is

reached on two different

wavelengths as it were. Of

course, there can be no

arias or any other kind of

self~contained musical

pieces in these operas, as

they would only disturb the

main purpose - the optimum

effect of the words.

"Il Ritorno d’Ulisse” is

therefore very different

from the musically rich

madrigal opera “l’Orfeo”.

The original sub-titles of

the two works show this

difference very clearly:

“l’Orfeo” is termed “Favola

in Musica” while “Ulisse” is

called "Dramma in Musica".

Our “music drama” is,

however, just as far removed

from "l’Orfeo" as from the

baroque opera proper, which

came into fashion soon

after. In this, the

individual singer was the

attraction and the focal

point; the words, the action

became less and less

important. This kind of

baroque opera with its

self-contained musical

numbers and arias soon

became a musical revue that

cried out for reform.

It can therefore be seen

that, from the dramatic

point of view, “Ulisse” is

not yet a true baroque

opera. The Prologue,

consisting of the 13th -

23rd cantos of the Odyssey,

is also in renaissance

character, not a classical

heroic drama or ancient

Roman theme as was popular

in the high baroque period.

Poet and composer have

adhered to the original poem

with almost pedantic

accuracy. The personal

characterization of the

suitors and all other

subsidiary figures has been

taken over in the minutest

detail. Since the educated

public of that time knew

every detail of this

principal work of Greek

poetry, Badoaro and

Monteverdi could dispense

with a dramatic development

of tension and relaxation.

They illustrated the

well-known plot, as it were,

and could thus also dispense

with the one personal

characterization or the

other, since all the

characters would anyway have

been previously known and

familiar to the listener.

As was the general practice

at that time, the work is

introduced by a symbolic

Prologue: man is a frail toy

in the hands of the three

Fatal Powers: Time, Fortune

and Love. The gods are also

subjugated to these powers.

The drama proper thus shows

the human being as a toy at

the mercy of the gods’

caprice, while the gods

themselves are no more than

immortal supermen at the

mercy of the Fatal Powers.

The action thus takes place

on three planes:

1. the Fatal Powers in the

Prologue,

2. the Gods in their scenes

of the first and last acts.

(ln the first act Neptune

will prevent Ulysses’s

homecoming to punish him for

blinding his son Polyphemus.

In the last act Neptune lets

himself be placated by the

other gods, Ulysses may

finally find rest and

Penelope can recognize him.)

3. The action proper,

In addition to the clearly

defined scenes on each of

the three planes, there are

three more points at which

world of the gods and that

of men come into conntact:

when Minerva comforts and

advises Ulysses, when she

brings Telemachus from

Sparta in her cloud chariot

and when she encourages

Ulysses on his return home

and finally stands by him in

his fight against the

suitors.

Performance

The form in which

Monteverdi’s late operas

have come down to us

presents an abundance of

problems that confront the

musicologist and the

practical musician alike

with almost impossible

tasks. Every individual

interpretation must

therefore be regarded as an

attempt at realizing one of

many possibilities. A claim

to definitiveness can never

be made in this case,

neither would it be the

object of the exercise.

Neither “Il Ritorno

d’Ulisse” nor

“l`lncoronazione di Poppea"

has come down to us in

Monteverdi’s manuscript, but

in contemporary copies. What

is more, we cannot speak of

a full score in the normal

sense: the entire work is

written on two staves, one

for the vocal parts, one for

the bass. Only in a few

ensembles, trios and duets

nnd in the few brief

instrumental pieces - in

five parts in “Ulisse” - is

the notation on three to

five staves. The basses are

only figured in exceptional

cases, so that not even the

harmony is clearly

perceptible from the written

notes. lt has to be deduced

from the contemporary rules

passed down to us in

instructional works. How

difficult that is, and how

many different possibilities

of harmonization Monteverdi

himself saw, can be studied

in some of his other works,

such as the two versions of

the two versions of the

Lamento d'Ariana or the two

versions of the instrumental

movements in “Poppea”, which

has come down to us in a

Venetian and a Neapolitan

copy of the same work. The

bass is the same in both

versions, but one is in

three parts and the other in

four, the realization of the

harmony being completely

different.

But there are more than

enough problems quite apart

from the harmony: for

instance, whether the

preserved “scores” represent

parts for the conductor that

need to be supplemented, or

whether they contain the

complete work as it is ti be

performed, in other words,

whether they are only a

frameworks, a skeleton that

first has to be clothed with

flesh in order to be

complete, or whether they

are already complete in this

form. It is obvious that

there is wide scope here for

alll kinds of doctrines, and

today we can already fin the

musical fruits of each

of these doctrines

somewhere, The extreme

possibilities are:

1. to perform the entire

work only with hnrpsichord,

letting the ritornelli be

played by a string quintet;

2. to orchestrate the entire

work, thus filling the space

between the bass and the

upper part with an

orchestral tecture.

The second possibility, of

course, offers an endless

variety of solutions with

the styles of orchestration

of the 17th to the 20th

centuries. All other

possibilities, including

that chosen in this

recording, lie somewhere

between these two extremes.

It is posssible to find some

indications of the

instrumentation in the

manuscripts: notes like

“tutti gli stromenti” or

“Violini” or “Ritornello”.

Occasionally instrumental

movements too have only the

uppermost part, or even the

bass, given in the “score”;

the other parts must be

added. There are also other

Venetian opera scores

written shortly after

“Ulisse” or “Poppea” which

contain even clearer

indications of the addition

of supplementary parts, some

lines between the vocal and

bass parts being left empty

in certain places. It is not

possible to state here all

the reasons that speak for

and against an

instrumentation; we are

convinced that Monteverdi

took it for granted, at

least for certain

performances. The decisive

question is, then, in which

passages instruments should

be used, and which should he

accompanied by continuo

only. Are there musical

criteria according to which

these passages can be

distinguished from one

another? The vocal parts and

the bass have been set in

two different, clearly

recognizable ways, which can

be called “recitative-like”

and "arioso”. These two

different modes of writing -

beside the already mentioned

notes in the manuscripts and

the lines left empty in the

other opera scores following

the same principle - give us

the formal scheme according

to which the instrumentation

ist to be worked out. (A

particularly fine example of

this arioso/recitative

alternation determining the

instrumentation is provided

by Penelope’s first

monologue. Here the thrice

repeated “torna, torna, deh

torna Ulisse" and “torna il

tranquillo al mare” stands

out in arioso style from the

big recitative.)

The instruments used here

are those which were in

general use in ltaly at that

time: above all string

instruments of the violin

family (also a viola da

gamba for the continuo),

four recorders for gentle

and brilliant scenes, two

piffari and a dulcian for

pastoral and comic scenes,

three trombones for

accompanying Neptune and

other passages where gravity

is called for, and a trumpet

in C and D, which was

obligatory at that time for

appearances of the gods.

These melodic instruments,

which are also given solo

passages in places, are

joined by an abundance of

continuo instruments: a

large Italian harpsichord

as the main instrument, a

small virginal for

accompanying the recitatives

of Melanto, Eurimaco and

Anfinomo, two lutes

and a chitarrone for

the tutti continuo and for

accompanying the songs of

Melanto, Eurimaco and

Anfinomo, also in

combination with the organ

for accompanying the

recitatives of Ulisse,

Telemaco and Ericlea, a harp

mainly for accompanying

Penelope, but occasionally

for Ulisse too, organ

for the gods’ scenes,

Telemaco, at times also

Eumete and in the tutti, and

a regal for Neptun,

Antinoo and the comical

passages of Iro.

The musical text follows in

principle the original

manuscript preserved in the

National Library, Vienna.

Likewise the literary text.

Obvious mistakes have been

corrected without further

comment.

In this recording, which was

made in conjunction with a

stage performance, we have

attempted to make the stage

action clear on the record.

The positions of the

characters follow a certain

stage production pattern, so

that Penelope for instance -

as a symbol of constancy -

is always on the left-hand

side of the stage while her

adversaries, the suitors,

are always on the right. The

coming and going of the

various characters is only

suggested, except when

Minerva and Telemaco

approach from the distance,

hovering in the cloud

chariot. Movement on the

stage has also been

recorded, e. g. when the

unhappy Iro runs to and fro

between the scatterred

bodies of the suitors.

The accompanying orchestra

has been recorded in a

seating arrangement that

remains constant; the

instruments that accompany

in each case can thus always

be easily localized.

In our recording of “Ulisse”

we have employed in

principle only such

possibilities as were usual

in Monteverdi’s time. Even

peculiar sound effects as in

the case of Neptune were

known (singing through

megaphones or in echo

chambers) and used to

dramatic purpose, just as

were all kinds of stage

machinery.

It has not been our

intention to present a

definitive version with this

recording.

We know that there are

infinite possibilities for

the performance of this

work: some which are sure to

be bad, and many that are

good and right.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|