|

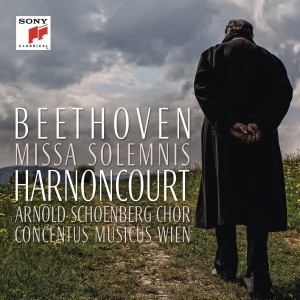

1 CD -

88985313592 - (p) 2016

|

|

| Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Missa solemnis, Op. 123 |

|

81' 33" |

|

| - Kyrie |

9' 56" |

|

1

|

| - Gloria

|

17' 48" |

|

2

|

- Credo

|

19' 56" |

|

3

|

| - Sanctus |

3' 44" |

|

4

|

| - Benedictus |

13' 07" |

|

5

|

- Agnus Dei

|

17' 02" |

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

| Laura Aikin,

Soprano |

|

| Bernarda Fink,

Alto |

|

| Johannes Chum,

Tenor |

|

| Ruben Drole,

Bass |

|

|

|

Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

master

|

|

|

|

| Concentus Musicus

Wien |

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman, violone |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, violin |

-

Brita Bürgschwendtner, violone |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, violin |

-

Alexandra Diens, violone |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, violin |

-

Alexandra Dienz, violone |

|

| -

Maria Bader-Kubizek, violin |

-

Rudolf Wolf, flauto traverso |

|

| -

Annette Bik, violin |

-

Reinhard Czasch, flauto traverso |

|

| -

Christian Eisenberger, violin |

-

Hans-Peter Westermann, oboe |

|

| -

Editha Fetz, violin |

-

Marie Wolf, oboe |

|

| -

Thomas Fheodoroff, violin |

-

Rupert Frankhauser, clarinet |

|

| -

Silvia Iberer, violin |

-

Georg Riedl, clarinet |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel-Vock, violin |

-

Alberto Grazzi, bassoon |

|

| -

Veronica Kröner, violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich, bassoon |

|

| -

Annemarie Ortner, violin |

-

Katalin Sebella, contrabassoon |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter senior, violin |

-

Hector McDonald, horn |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter junior, violin |

-

Georg Sonnleitner, horn |

|

| -

Florian Schönwiese, violin |

-

Athanasios Ioannou, horn |

|

| -

Irene Troi, violin |

-

Aggelos Sioras, horn |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, viola |

-

Atay Bagci, horn |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, viola |

-

Andreas Lackner, trumpet |

|

| -

Ulrike Engel, viola |

-

Markus Kuen, trumpet |

|

| -

Magdalena Fheodoroff, viola |

-

Thomas Steinbrucker, trumpet |

|

| -

Pablo de Pedro, viola |

-

Otmar Gaiswinkler, trombone |

|

| -

Dorothea Sommer, viola |

-

Hans Peter Gaiswinkler, trombone |

|

| -

Rudolf Leopold, violoncello |

-

Johannes Fuchshuber, trombone |

|

| -

Dorothea Schönwiese, violoncello |

-

Dieter Seiler, timpani |

|

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Stephaniensaal,

Graz (Austria) - 3-5 luglio 2015 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Mathis

Huber / Michael Schetelich / Franz Josef

Kerstinger

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Sony

- 88985313592 - (1 cd) - 81' 33" - (p)

2016 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

“From

the heart - may it return to the

heart!"

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt and Beethoven's Missa

solemnis - a

long struggle to come to terms with a

key work has become the conductors

legacy

For decades the Missa solemnis

was a major part of what Nikolaus

llarnoncourt called his personal

"Beethoven problem". Together with the

tricky but ultimately visionary finale

of Fidelio and the

erratic block that is the Ninth

Symphony, the Missa solemnis was

one of those works to which he struggled

for a long time to gain access. As a

cellist with the Vienna

Symphony Orchestra he got to know it in

seven different interpretations, not one

of which seemed to him to do it justice.

lfle did not conduct the Missa

solemnis himself until 1988, the

year in which he first

conducted a stage production of Fidelio

at the Hamburg State Opera. It

was during his detailed preparations for

a performance with the Residentie Orkest

of The Hague at the Schubertiade in Feldkirch

that - as he later recalled - "the

scales fell from his eyes". "All

that had seemed to me to be empty bathos

suddenly turned into its opposite."

The next step occurred at the Salzburg

Festival, where Harnoncourt made his

belated début in 1992,

conducting the Missa solemnis in

the Großes Festspielhaus -

he always believed that important sacred

works should not be confined to

churches, a belief that in this case was

doubly justified, for quite

apart from the fact that a work of such

vast dimensions as this would far exceed

the scope of even the most festive

solemn mass, not even the work's first

performance took place in an

ecclesiastical context, for all that it

was dedicated to a high-ranking

member of the church, The product of a

lengthy genesis extending from 1817 to

1823, it was dedicated to Beethoven's

former pupil and friend, Archduke

Rudolph of Austria, and was intended to

mark the latter’s enthronement as

archbishop of Olomouc. It may be

mentioned in passing that Rudolph was

the youngest brother of Archduke Johann,

Harnoncourt's great-great-grandfather.

One of the secrets of Nikolaus Harnoncourt's

interpretation was his ability to

develop this monumental work from

silence, keeping the usual frenzied

sonorities within bounds and allowing

the individual voices to emerge from the

overall textures whenever they needed to

be heard on their own. When the words "Pleni

sunt coeli" in the Sanctus are sung not

by the chorus but by the soloists, as

Beethoven originally notated them, then

the impact of the message is increased.

As far as this message is concerned, few

other conductors were as conscious as Harnoncourt

of the meaning of the Mass's

words, with the result that he always

ensured that the manifold interpretative

possibilities concealed within the latin

text were carefully aligned with the

music. The subtle distinctions in the

musical message that resulted from this

knowledge rested in part on the

conductor's extremely careful approach

to Beethoven's deliberately detailed

dynamics, which were always taken

seriously, their apparent contradictions

notwithstanding. This often meant a good

deal of experimentation in the rehearsal

room. At the same time Harnoncourt's

"tempo dramaturgy" always resulted in a

coherent structuring of the work and in

a natural eloquence.

Beethoven notated some thirty different

tempo markings for his Missa

solemnis - almost as many as in

one of Mozart's operas.

But unlike Mozart, Beethoven

does not return periodically to a "basic

tempo", for most of his tempo markings

are used only once, and he appears to

have been concerned to ensure that his

wishes were expressed as precisely as

possible. At the start of the Kyrie, for

example, with its alla breve

marking, we find the

performance marking Assai sostenuto.

Mit

Andacht (Fairly sustained. With

raptness), while the start of the

Sanctus, in 2/4-time, is marked Adagio.

Mit Andacht. The second section of

the Benedictus bears the instruction Andante

molto

cantabile e non troppo mosso.

There is something unusually furious, by

contrast, about the presto ending of the

Gloria and the chorus's desperate cries

in the Agnus Dei.

The final stage in Harnoncourt's

engagement with Beethoven's key work

came in the summer of 2015, when he

conducted it at the styriarte Festival

in Graz - the source of the present

recording - and at the Salzburg Festival.

In this way it became the coping stone

on the career of the conductors great

adventure with his Concentus Musicus

and with the Arnold Schoenberg Chor,

an adventure that came to a sadly

premature end in March

2016. These two ensembles came closer

than any others to the conductors

intentions, having internalized his

working method and learnt to implement

his instructions right down to the very

last detail. ln this way what comes from

the heart goes back to the heart.

The interview that follows took place in

May 2015.

Herr Harnoncourt, could the Missa

solemnis be

likened to

an

attempt to prove the existence of God

through music?

Beethoven would never have attempted to

do any such thing. Proving the existence

of God would spell the

end of any faith, any religion. On the

other hand, it could be argued that all

art - and music in particular -

represents an engagement with the

transcendental. I have the impression

that Beethoven was constantly flirting

with the incomprehensible, opening up

unexpected approaches and making the

invisible visible or, rather, audible.

We are guided through so many

transformations that by the end of the

process we ourselves could be said to

have been transformed.

In writing this

work, Beethoven engaged with the words

of the latin Mass in an

entirely personal and unprecedented way.

Above all, Beethoven draws on what

stylistically speaking is the archetypal

basis of all church music, time and

again stressing what the church modes

have to offer him and emphasizing the

importance of mastering questions of

musical rhetoric. The result is a unique

work: there had been nothing like it

previously. Every section of the Mass

is interpreted in a novel way. But for

us today the work no longer sounds

unique: we have heard it all before. The

difficulty of performing it

consists in rediscovering this "unheard-of"

element and allowing us to experience it

for ourselves as if for the very first

time.

When you conducted the work in

Salzburg in 1992,

you used natural trumpets, early

trombones and

an old

set of timpani.

Now you are performing it with the

Concentus Musicus. What difference

does this make?

The stringing of the string instruments

plays an important role because the way

in which the overtones are built up and

the sound mixture that you ind with gut

strings are entirely different. And with

early woodwind instruments you get a

much more differentiated sound in terms

of their sonorities and keys, something

that over the years has been lost. With

a modern Boehm flute, all of the holes

are the same size, so you can no longer

cover them with your fingers alone and

they need to be fitted

with keys. Every note and every key

sounds the same, there are only "false"

intervals. Above all, there is no longer

a pure third. Or take the clarinets: in

his Missa

solemnis Beethoven demands

clarinets in A, B flat and C, but no

orchestra uses clarinets in C any

longer. Today everything is a transposed

major or minor, and few listeners are

aware any longer of the characteristics

of the different keys.

The Missa solemnis

is in D major but it modulates via

E-flat major to the relative key

of B minor. What does D major stand

for?

D major stands for dominion, kingship

and God, The intervals are relatively

pure. D major is the key of the

trumpets, which were in any case the

privileged instruments of rulership.

Which pitch do you and the Concentus

use for

Beethoven?

a'=430 Hz. This is

substantially lower than is usually

found today. But this is the pitch that

Verdi demanded even for the late 19th

century.

Does the lower pitch not remove some

of the excess pressure? After all, the

risk factor in this

work always

relies on the sense of pathos and

hysteria...

You can't get round that problem. It's

still very high for the sopranos.

Beethoven could be said to have written

failure into his score, and he did so in

a way that you can actually hear. He

wanted to demonstrate the impossible. In

the case ofthe strings he writes notes

that are no longer on the fingerboard

and which effectively have to be

snatched from the air. The clarinet and

the horn, too, have notes that can no

longer be produced - and

there are dynamic instructions that

appear to be unrealizable. When the horn

plays a high C, it's a natural note that

is normally fairly loud. But Beethoven

demands that it be played pianissimo

or even pianississimo. What are

we supposed to do? You need a ruse! You

encounter problems like these at every

turn.

For listeners,

the idea that failure

is written into the score is perhaps best

illustrated by

the vocal soloists, where there is

often a problem with stamina.

That's the question. The problem today

is partly based on the fact that modern

performance practice no longer

acknowledges a piano marking. We know

how furious and desperate Beethoven was

when conductors ignored his dynamic

markings - he wrote at some length about

the performance of his Second Symphony

at a time when his hearing was not yet

completely wrecked. He regarded all

attempts to reduce his dynamics to a

single level as a garbling of his work.

We have to approach this matter with

great care. Although this doesn't only

apply to the instruments, it's certainly

easier with period instruments.

Beethoven's

setting of the Agnus

Dei strikes me as particulalrly

remarkable. Although this

section has only six lines of text,

Beethoven creates a vast, two-part

movement that lasts

almost

as long

as the Gloria, with this alarming battle

painting that culminates

in the

plea for peace...

In most settings of the

Mass, the "Dona nobis

pacem" is interpreted in such

a way as to suggest that peace already

exists. And yet the words mean that it

is not peace that reigns but

catastrophe. Beethoven does not say "Thank

you!" but "Give!"

This is particularly thrilling in the Missa

solemnis. For

me, this begs the question as to whether

peace can exist at all. I see this

psychologically. Of course, memories of

the Napoleonic Wars were still fresh in

people's minds at this time, and you may

even be able to see a burning city in

the music. But the battle painting

tends, rather, to depict the conflict

that goes on inside us. It

is a plea - as Beethoven himself said -

for "inner and outer peace".

And it strikes me as far more plausible

that it is the inner conflict that

constitutes the actual drama. The inner

aspect is more important than the outer

one. But this is true of each and every

one of us.

Monika

Mertl

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|