|

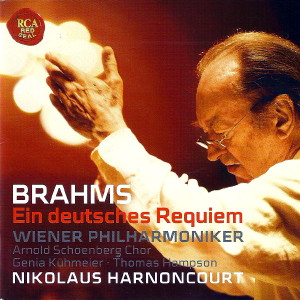

1 CD -

88697 72066 2 - (p) 2010

|

|

| Johannes

Brahms (1833-1897) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ein deutsches Requiem, Op. 45 |

|

72' 01" |

|

|

|

|

|

- Selig sind, die da Leid tragen

- Chor (Ziemlich langsam und mit

Ausdruck)

|

9' 58" |

|

1

|

- Den alles

Fleisch, es it wie Gras - Chor

(Langsam, marschmäßig)

|

16' 02" |

|

2

|

- Herr, lehre doch mich - Bariton

& Chor (Andante moderato)

|

10' 47" |

|

3

|

- Wie lieblich sind deine

Wohnungen - Chor (Mäßig bewegt)

|

5' 54" |

|

4

|

- Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit - Sopran

& Chor (Langsam)

|

7' 00" |

|

5

|

- Denn wir haben hie

keine bleibende Statt - Bariton

& Chor (Andante)

|

12' 35" |

|

6

|

- Selig sind die Toten - Chor

(Feierlich)

|

9' 45" |

|

7

|

|

|

|

|

| Genia

Kühmeier, Soprano |

|

| Thomas

Hampson, Baritone |

|

|

|

| Arnold

Schoenberg Chor |

|

| Wiener

Philharmoniker |

|

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Musikverein,

Vienna (Austria) - dicembre 2007 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

| Martin

Sauer / Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione CD

|

| RCA

"Red Seal" - 88697 72066 2 - (1 cd) -

72' 10" - (p) 2010 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

| Notes |

Strictly

speaking, the genesis of Brahms‘s German

Requiem stretches back to the composer's

youth when, as a twenty-year-old, he

left his native Hamburg for the first

time in his life: the earlier,

unacknowledged prodigy from a modest

lower-middle-class background had become

a mature pianist thanks to his lessons

with the city’s leading music teacher,

Eduard Marxsen. In April 1853 he set off

with the violinist Eduard Reményi on a

concert tour of Germany. En route he met

a number of eminent figures from the

world of music, all of whom were to

influence his subsequent career and who

included the violinist, composer and

conductor Joseph Joachim, the pianist

and composer Franz Liszt, who was then

in Weimar, and finally, Robert and Clara

Schumann, with whom he became so

friendly that he remained with them in

Düsseldorf for a period of several

weeks. All three took a positively

delirious delight in each other’s

company, a situation that was, however,

made more difficult when Brahms secretly

and hopelessly fell in love with Clara

Schumann, who was almost fourteen years

older than he was. Her husband was so

enthusiastic about the talented young

musician that on 28 October 1853 he

published an appreciative article in the

Neue Zeitschrift für

Musik, hailing Brahms as a future

saviour of music: "I felt certain that

[...] there would suddenly emerge an

individual fated to give expression to

the times in the highest and most ideal

manner, who would achieve mastery, not

step by step, but at once, springing

like Minerva fully armed from the head

of Jove. And now here he is, a young

fellow at whose cradle graces and heroes

stood watch. His name is Johannes

Brahms."

The first of Brahms‘s published works

appeared in Leipzig at the end of 1853,

and yet they left their composer still

feeling unsure of himself, a point that

emerges not least from his great Sonata

in D minor for two pianos, which he

began in 1847 and continued to work on

until 1854, before discarding it. While

working as chorus master in Detmold from

1857 to 1860, he toyed with the idea of

turning it into a symphony but finally

used the material as the basis of his

First Piano Concerto in D minor of 1859.

The march-intermezzo that was originally

intended for the sonata/symphony later

became the second movement of the German

Requiem. During the years that

followed, Brahms sought to deepen his

understanding of the technical tools of

his trade by studying counterpoint with

Joachim and by taking a detailed

interest in the vocal music of

Palestrina, Schütz, Handel and Bach. In

1856 he started work on a Missa

canonica in D minor for

unaccompanied choir that he again

discarded. And from 1859 to 1862 he

conducted a women's choir in Hamburg.

During the 1863/64 season, finally, he

was chorus master of the Vienna

Singakademie, where he acquired a

practical knowledge of the oratorio

repertory. The death of his mentor,

friend and rival Robert Schumann in 1856

was a bitter blow for him, and it is

possible that one response to his loss

was the Begräbnisgesang op. 13

for choir and wind band that he wrote in

Detmold in November 1858. A visionary

funeral march, it is an important

precursor of the Requiem in

terms of both words and music.

At first sight, Brahms‘s decision to

start work on his Requiem

appears to have been prompted by the

death of his mother in February 1865,

and yet the earliest sketches may well

date back to 1861, the fifth anniversary

of Schumann's death. Only gradually did

the work acquire the form that is

familiar to us today: the penultimate

movement was completed by April 1865 and

the first two movements had at least

been sketched by this date; the full

score of the work's initial version was

finished by the summer of 1866. It was

also performed piecemeal: the first

three movements were introduced to a

Viennese audience in the city’s

Redoutensaal at the second concert of

the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde on 1

December 1867. The chorus was the local

Singverein and the conductor was Johann

Herbeck. In the wake of the performance,

Brahms undertook a number of changes to

the score, adding an organ part and - in

the event of the non-availability of

such an instrument - a part for a

contrabassoon.

The real first performance was given in

Bremen Cathedral on 10 April 1868, when

Brahms himself conducted the city’s

200-strong Singakademie at the

invitation of its principal conductor,

Carl Martin Reinthaler. The large

orchestra featured no fewer than

twenty-four violins. The programme

included not only a number of pieces for

solo violin played by Joseph Joachim,

who almost certainly acted as leader for

the rest of the concert, but also three

movements from Handel's Messiah,

"Behold the Lamb of God", "I know that

my Redeemer liveth” and the "Hallelujah"

Chorus, and, finally, the aria "Erbarme

dich" from Bach’s St Matthew Passion

sung by Joachim's wife, Amalie Weiss.

The British Brahms scholar, Robert

Rascall, has noted that this group of

works offers "interesting commentary on

the structure, expressive range and

message of the Requiem itself.".

In particular, "I know that my Redeemer

liveth" for soprano solo served as a

model for what is now the Requiem’s

fifth movement, "Ihr habt nun

Traurigkeit", which Brahms added only

after the Bremen performance and which

was originally intended to be in fourth

position. The first complete performance

of all seven movements was given in

Dessau at Christmas 1868, when Adolf

Schubring conducted a chorus of twelve

with piano accompaniment. In January

1869 he reported enthusiastically on the

performance in the columns of the

Leipzig-based Allgemeine

musikalische Zeitung. The first

complete performance with full orchestra

and chorus was conducted by Carl

Reinecke within the framework of the

Leipzig Gewandhaus's seventeenth

subscription concert on 18 February

1869. The work's subsequent history is

one long success story, confirming

Brahms’s reputation as one of the

leading composers of his age. Between

1869 and 1876, no fewer than

ninety-seven performances are known to

have taken place in Europe alone.

It is worth noting that the work found a

home for itself in the concert hall

rather than in church, a development

that undoubtedly reflects the composer’s

interdenominational outlook. In the

course of the 19th century organizations

founded to perform oratorios enjoyed a

tremendous vogue with ever-increasing

numbers of members: between 1859 and

1878, the Vienna Singverein, for

example, grew from 122 members to 360.

As a result, there were many concerts at

this time with very large choirs and

correspondingly large orchestras: in

1882, for instance, Brahms conducted a

performance of his Requiem with

the Hamburg Bach Society, which fielded

a choir of 225 members and an orchestra

of seventy-six. Even greater forces are

known to have been involved in the major

music festivals of the time. In general,

however, it was local conditions and the

particular venue that dictated the size

of the orchestra and choir and the way

in which they were arranged on the

stage. According to a contemporary

seating plan by Henri Kling, the stage

of the old Leipzig Gewandhaus during the

musical directorship of Carl Reinecke

from 1860 to 1895 could accommodate up

to 540 choristers in addition to twenty

first and twenty second violins,

thirteen violas, twelve cellos and ten

double basses alongside the wind

players.

At the same time, however, we know that

Brahms preferred smaller orchestras.

According to Robert Pascall, the

orchestra that gave the first

performance of his First Symphony in

Karlsruhe in 1876 comprised fortynine

players, while the Meiningen Hofkapelle,

with which he worked closely from 1880

onwards, had a similar number. When his

Fourth Symphony was performed there in

1885 he resisted the idea of increasing

the number of strings. He also prepared

a version of his Requiem for

solo voices and two pianos that was

intended to be performed in smaller

venues and that enjoyed considerable

popularity for many years, a popularity

that shows some signs of returning

today. Brahms himself anticipated this

development when, adopting a note of

irony, he wrote to his publisher, Fritz

Simrock: "I have abandoned myself to the

noble task of making my immortal work

palatable to the four-handed soul. It

cannot perish now."

In his excellent monograph on Orchestral

Performance Practices in the

Nineteenth Century - Size,

Proportions, and Seating [Ann

Arbor, Michigan, 1986, reprint 2010],

Daniel J. Koury reproduces more than one

hundred seating plans from the 19th

century, the vast majority of which

indicate that the first and second

violins were arranged antiphonally to

the left and right of the conductor. It

is clear from Brahms’s score that he,

too, counted on this arrangement in his

Requiem. Instruments from the

years before 1900 were up to a third

smaller than they are today, while the

wind instruments had narrower bores and

were also far more colourful than many

modern instruments. The lower Paris Kammerton

was introduced to Viennese orchestras in

1862, while valve trombones remained in

use there until as late as 1883. Wound

gut strings were preferred. The sort of

permanent vibrato that gradually emerged

in the 1930s was not yet customary. As

one of the most influential violinists

of his age, Joseph Joachim employed a

subtly differentiated bowing technique

to achieve the intensity of his playing.

The tuning, moreover, was harmonically

pure.

The German Requiem is the first

of only six works by Brahms for which

authentic metronome markings exist. They

derive from suggestions made by the

composer's friend, Carl Martin

Reinthaler, and indicate fluid tempi. If

these markings are observed, a

performance of the Requiem

should last between sixty and sixty-five

minutes. Of course, these are merely

guidelines and need to be interpreted

flexibly, forthe English pianist Fanny

Davies described Brahms's style of

performance as follows: "Brahms’s manner

of interpretation was free, very elastic

and expansive; but the balance was

always there - one felt the fundamental

rhythms underlying the surface rhythms.

[...] He would linger not on one note

alone, but on a whole idea, as if unable

to tear himself away from its beauty. He

would prefer to lengthen a bar or phrase

rather than spoil it by making up the

time into a metronomic bar." Brahms

himself emphasized the importance of

rubato, but, like everything else, he

also stressed that shifts in the tempo

should be undertaken "con discrezione".

In short, the strict tempo of a movement

or work and the relationship between the

different tempi must retain their

significance, but imperceptible

transitions, ritardandos and

accelerandos were explicitly demanded as

a way of interpreting the piece as if it

were a living, breathing organism.

Brahms had been baptised into the

Lutheran faith in St Michael’s Church in

Hamburg, but when he came to assemble

the texts for his German Requiem,

he chose words for their

interdenominational appeal. As he

himself put it, he wanted to write

funeral music for people in general,

otherwise he might just as well have set

the Latin words familiar from the Mass

for the Dead. His profession of faith in

the age-old tradition of church music,

by contrast, is clear not least from the

fact that the whole of the work’s

thematic material is derived from

Luther’s Wer nur den lieben Gott

lässt walten. Other influences

include Handel`s Messiah,

Schubert’s Mass in E flat major and

Beethoven’s Missa solemnis,

Schütz's Musikalische Exequien

["eine teutsche Begräbniß Missa", i.e.,

"a German burial Mass"] and, especially,

Bach’s St Matthew Passion and Actus

tragicus. As such, this list

constitutes a compendium of early church

music of altogether exemplary status

similar to the one intended by Mozart

for his unfinished Requiem. At the same

time, Brahms’s German Requiem

itself pointed the way forward. Gabriel

Fauré, for example, took up the opening

of Brahms’s work in his own Requiem,

which is scored for lower strings and

which received its first performance in

1888. Writing in 1875, the doyen of

Viennese music critics, Eduard Hanslick,

noted that "In Brahms’s Requiem

we see the purest artistic means

employed in pursuit of the highest goal,

while warmth and depth of feeling are

combined with consummate technical

mastery. There is no-thing to dazzle the

senses, and yet everything is profoundly

moving. There are no novel orchestral

effects, but only new and grand ideas

and, the work’s richness and originality

notwithstanding, the most noble

naturalness and simplicity."

If the work creates the impression of

great clarity, this is due not least to

its symmetrical seven-part structure.

Formally related to one another, the

first and last movements provide a

framework for the Requiem as a

whole. Both share the words "Selig sind"

["Blessed are"] and both are in the key

of F major, a pastoral key traditionally

associated with the birth of Christ. The

second and sixth movements are the most

complex of all, and both are in minor

keys. The three middle movements are

lyrical intermezzos. At the same time,

however, the work's dramaturgical

structure is based on that of the

traditional Latin Mass for the Dead with

a number of central elements. An

important role is played by the funeral

march in movements I-III and VI; the

fourth and fifth movements include

elements of the Sanctus; the words of

the sixth movement clearly allude to the

Last Judgement, corresponding to the

liturgy’s "Libera me"; and the final

movement takes up the idea of the

procession to the grave, the "In

paradisum", a section of the liturgy

rarely set to music. The themes and

motifs from all the movements are hard

to identify at an initial hearing, even

though they are rigorously interrelated.

The three-note motif that accompanies

the opening words "Selig sind", F-A-B

flat, is also heard in inversion at the

start of the second movement [G flat-F-D

flat] and may derive from the Chorale Allein

Gott in der Höh sei Ehr. No less

striking are the triadic themes, the

triad being a long-established symbol of

the Trinity in music. Finally, there are

several allusions that will be picked up

only by insiders, references to other

sacred works that well-meaning friends

pointed out to Brahms, prompting what we

know to have been a typically surly

reaction on his part: he wanted his

music to create an impression on the

strength of its own internal merits

alone. And yet music lovers everywhere

will have no difficulty in recognizing

an allusion to the opening of the chorus

"O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß" from

Bach’s St Matthew Passion in the

opening bars of the Requiem’s

final movement.

Benjamin-Gunnar

Cohrs, Bremen

Translation:

Daphne

Ellis

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|