|

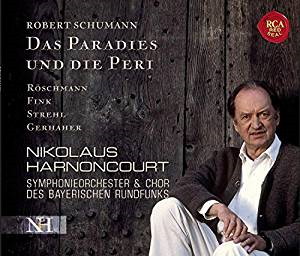

2 CD -

88697 27155 2 - (p) 2008

|

|

Robert

Schumann (1810-1856)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Das Paradies und die Peri,

Op. 50

|

|

|

|

| Oratorium - Libretto by Emil

Flechsig and Robert Schumann after the

oriental epic Lalla Rookh by

Thomas Moore |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Erster

Teil

|

|

27' 10" |

|

| - Nr. 1 - "Vor Edens Tor

im Morgenprangen" (Mezzosopran) |

3' 13" |

|

CD1-1 |

| - Nr. 2 - "Wie glücklich

sie wandeln" (Peri)

|

2' 44" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Nr. 3 - "Der Hehre

Engel, der die Pforte" (Rezitativ

Tenor, Engel) |

1' 58" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - Nr. 4 - "Wo find ich

sie?" (Peri) |

2' 39" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Nr. 5 - "So sann sie

nach" (Tenor) - "O süßes Land!"

(Quartett: Sopran, Mezzosopran,

Tenor, Bariton) |

1' 25" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - Nr. 6 - "Doch seine

Ströme sind jetzt rot" (Chor)

|

3' 24" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - Nr. 7 - "Und einsam

steht ein Jüngling noch" (Tenor,

Chor, Gazna, Der Jüngling) |

2' 52" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Nr. 8 - "Weh, weh, er

fehlte das Ziel" (Chor) |

2' 13" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - Nr. 9 - "Die Peri sah

das Mal der Wunde" (Tenor, Peri,

Chor) |

6' 42" |

|

CD1-10 |

| Zweiter Teil |

|

36' 17" |

|

- Nr. 10 - "Die Peri tritt mit

schüchterner Gebärde" (Tenor, Engel,

Chor)

|

3' 17" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - Nr. 11 - "Ihr erstes

Himmelshoffen schwand" (Tenor, Chor,

Peri) |

3' 50" |

|

CD1-12 |

- Nr. 12 - "Fort sreift von hier

das Kind der Lüfte" (Tenor, Peri)

|

3' 31" |

|

CD1-13 |

- Nr. 13 - "Die Peri weint, von

ihrer Tränen scheint" (Tenor) -

"Denn in der Trän' ist Zaubermacht" (Quartett:

Sopran, Mezzosopran, Tenor, Bariton,

Chor)

|

2' 42" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - Nr. 14 - "Im Waldesgrün am

stillen Seer" (Alt, Jüngling) |

3' 03" |

|

CD1-15 |

| - Nr. 15 - "Verlassener Jüngling,

nur das eine" (Mezzosopran, Tenor, Jüngling) |

4' 35" |

|

CD1-16 |

| - Nr. 16 - "O lass mich von der

Luft durchdringen" (Jungfrau, Tenor) |

4' 52" |

|

CD1-17 |

| - Nr. 17 - "Schlaf nun und ruhe

in Träumen voll Duft" (Peri, Chor) |

3' 49" |

|

CD1-18 |

| Dritter Teil |

|

36' 58" |

|

- Nr. 18 - "Schmücket die Stufen

zu allahs Thron" (Chor)

|

3' 10" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Nr. 19 - "Dem Sang von ferne lauschend"

(Tenor, Engel) |

3' 03" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - Nr. 20 - "Verstoßen!

Verschlossen auf's neu das Goldportal!" (Peri) |

4' 27" |

|

CD2-3 |

- Nr. 21 - "Jetzt sank des Abends

goldner Schein" (Bariton)

|

4' 25" |

|

CD2-4 |

- Nr. 22 - "Und wie sie niederwärts

sich schwingt" (Tenor, Bariton, Chor)

|

3' 59" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Nr. 23 - "Hinab zu jenem

Sonnentempel!" (Peri, Mezzosopran,

Tenor, Der Mann) |

6' 53" |

|

CD2-6 |

- Nr. 24 - "O heil'ge Tränen

inniger Reue" (Quartett: Sopran, Alt,

Tenor, Bariton, Chor)

|

4' 12" |

|

CD2-7 |

- Nr. 25 - "Es fällt ein Trpfen

aufs Land" (Peri, Tenor, Chor)

|

7' 20" |

|

CD2-8 |

- Nr. 26 - "Freud', ew'ge

Freude, mein Wek ist getan" (Peri,

Chor)

|

6' 55" |

|

CD2-9 |

|

|

|

|

| Dorothea

Röschmann, Soprano (Peri) |

Bernarda

Fink, Alto (Engel) |

|

| Christoph

Strehl, Tenor (Narrator)

|

Christian

Gerhaher, Baritone (Gazna)

|

|

| Malin

Hartelius, Soprano

(Jungfrau)

|

Werner

Güra, Tenor (Jüngling)

|

|

| Rebecca

Martin, Mezzo-soprano)

|

|

|

|

|

| Chor des

Bayerischen Rundfunks / Peter

Dijkstra, Chorus Master |

|

| Chorsolisten: Gerald

Haußler, Bass (Der Mann) /

Theresa Blank, Alt |

|

| Symphonieorchester

des Bayerischen Rundfunks |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Herkulessaal, Munich

(Germania) - 18-22 ottobre 2005 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfram Graul (BR) /

Firedemann Engelbrecht (Teldex Studio

Berlin) / Klemens Kamp (BR) / Michael

Brammann (Teldex Studio Berlin) |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

RCA "Red Seal" - 88697 27155 2

- (2 cd) - 56' 46" + 44' 24" - (p) 2008

- DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Robert Schumann’s

death in a mental asylum; the works

written during the years of his

illness, which his wife Clara, Johannes

Brahms and Joseph Joachim

kept from the public

or even destroyed (!)

out of a false sense of respect; the

preference shown by posterity for a

handful of orchestral works,

concertos, Lieder and piano

pieces: all this has led to the

widespread neglect to this day of a

significant part of the composer’s

oeuvre - in particular

the choral works,

oratorios, the Requiem, the Missa

Sacra, the opera Genoveva

and the late works dating from

1852 onwards. Paradise and the

Peri is one of the bold

compositions from Schumann’s

pen that conservative 20th century

aesthetes dismissed with a shrug of

the shoulders because they couldn’t be

pigeon-holed - works

that are only gradually achieving

recognition for their innovative and

progressive character. Yet Clara

Schumann wrote: "I

believe it is the finest thing he has

ever written. He is putting his entire

heart and soul into it, though,

working with such passion that I

sometimes fear he may damage his

health. But then I am

happy again to see him so involved."

The term ‘oratorio' is only superficially

suited to describe the work. It

is really more of a ‘lyrical story',

reminiscent of Schubert’s Lazarus

fragment and in its idiosyncratic

concept anticipating compositions by

Wagner (Tannhäuser,

Parsifal), César Franck (Rédemption),

Debussy (Le Martyre de St. Sebastién) and

even Vaughan-Williams (The

Pilgrim's Progress). The text is

based on an oriental epic by the Irish

poet Thomas Moore, Lalla Rookh.

This book was a huge bestseller in its

day and Schumann read as a child, his

father having published a German

translation in 1822. For a long time,

the composer planned to turn the

material into an opera. In 1841

he and his friend Emil Flechsig began

writing the libretto, which was

completed on 6th January1842;

Schumann then started work on the

score. But not until 19th June

1843 was he able to announce: "I

completed my Paradies und

Peri last Friday, my biggest

work to date and i hope my

best one as well. With my heart filled

with gratitude to Heaven for keeping

my creative powers so alive while I

wrote the music, I wrote “The End"

beneath the score. It is a great deal

of work producing a piece like this,

and in the process you really find out

what it means to compose more pieces

on this scale... The story of the Peri

is predestined to be set to music. The

whole idea is so poetic and so pure

that it filled me with

enthusiasm.”

In Persian mythology, a Peri is a kind

of fairy. As the child produced by the

union of a fallen angel and a human

female, the Peri is ‘impure’ and thus

cannot be admitted to Paradise. But

the guardian of the gates of Paradise

is moved by her longing, and says he

will let her in if she can wash

herself free of all sin. What he

doesn’t tell her is precisely what

offering she needs to make as “the

gift dearest to Heaven”. Thus the Peri

flies first of all to India, the

beauty of which land the libretto

praises amply. There, the fierce

warlord Gazna is leading a campaign of

conquest and a bloody battle is in

progress. When the last Hindu to

oppose the tyrant is slaughtered, the

Peri believes she has found the gift

she needs to get into Heaven: the last

drop of the fallen hero's blood.

Like Part One, the two following parts

of the work are divided into three

scenes each. First we hear about the

Peri’s fate; this is followed by a

description of a distant country, and

then the event is depicted that is

connected with the Peri’s gift to

Heaven. At the opening of Part Two,

the Peri is turned away: the angel

guarding the entrance to Paradise

tells her that her offering

is not worthy. She flies to Africa and

takes a cleansing bath in the (then

undiscovered) source ofthe Nile.

Afterwards, she follows the river

northwards. But in Egypt, the plague

is rife. She retreats to an oasis,

where she encounters a youth who is

infected and left his still healthy

beloved in order to protect her. But

the maiden follows him, gets infected

in turn, and they both die, united in

one final kiss. The Peri catches the

last sigh breathed by the two lovers.

At the beginning of Part Three we

enjoy a glimpse of Paradise, where the

steps leading up to Allah’s throne are

adorned by the most beautiful houris.

The Peri again appears at Heaven’s

gates, but like its predecessor, her

second gift is rejected too. She won’t

be put off her quest, though, and

resolves to travel all round the world

if needs be. Now

she takes off to a third, legendary

‘Promised Land’,

namely ancient Syria. On the banks of

the River Jordan

she meets a group of Peris, who share

her fate and likewise want to gain

admission to Paradise - though the

music at this point is somewhat

ambiguous: perhaps the other Peris

only mean it ironically. At the sun

temple in Baalbek, the Peri then

observes a strange scene: An old

sinner, wild of countenance, comes

across a pretty and innocent young lad.

But he refrains from violating him,

for the fearless boy is kneeling in

prayer. This touches the old man so

that he kneels down beside him, weeps

over his past wrongdoing, and prays

with him. For the Peri, the aged

lecher’s tears represent the key to

the gate of Paradise. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt has said: "A

part from the splendid music, which

has often been described as imperfect,

it is the work’s form that moves me -

the fact that each part ends with the

certainty of having achieved the goal,

and not with rejection.

Thus each part starts in the same way

as Part One, namely in a mood of

despair. But the Peri won't

give up her quest." Schumann himself

may well have identified with the Peri

for quite a while.

The composer himself conducted the first

performance in the Altes Leipziger

Gewandhaus on 4th December 1843, and

to triumphant effect: this proved to

be the turning-point in a career that

had hitherto been dogged by failure.

During his own lifetime, Paradise

and the Peri was performed more

than fifty times at home and abroad,

bringing Schumann international fame.

"Many of my

compositions", he

far-sightedly wrote to Clara on 13th

April 1838, "are so

hard to understand because they relate

to distant interests: I

am touched by all kinds of

contemporary peculiarities that I then

have to express in music." But he

would have been horrified at the

extent to which his oratorio was

misrepresented in the following

century. In the First World War the

work was used to transfigure the

'glorious' soldiers killed in action,

and in World War II Hitler’s

propaganda minister ]osef Goebbels

commissioned Max Gebhard, director of

the Nuremberg Conservatoire at the

time, to make an arrangement of the

work emphazing the element of

sacrificial death: this version had

its première in 1943

under the baton of Kurt Barth,

accompanied by Nazi propaganda. The

misuse that the work suffered in the

two world wars may have been one

reason why Paradise and the Peri

then vanished almost completely from

the repertoire, like many other pieces

of Classical music that the Nazis

abused for political purposes. In

the postwar years, the viewpoint

gained currency that Paradise and

the Peri was Schurnann’s rather

immature ‘first oratorio’ (perhaps an

attempt to repress the uses it had

been put to), and this seemed to seal

its fate. Not until the 1980's

did a hesitant rediscovery of the work

take place.

All the themes and motifs are

skilfully developed. The musical form

is new and 'undogmatic',

as it were. It combines elements of

secular music (role allocation and

treatment of the chorus comparable

with opera, incorporation of the art

song) with traditional sacred music

(chorales, a tenor narrator similar to

Bach`s Evangelist, symbolism,

emotions, liturgy). In

the closing chorus of Part One - which

Schumann's friend Mendelssohn was to

use for the finale of his own oratorio

Elijah - the fugal theme (no.9,

bar 116) quotes the finale "Di

tai pericoli non ha timor"

from Mozart’s Davide Penitente,

known today as the "Cum

Sancto Spiritu" of the C minor Mass,

which was first published in 1840.

In Part Three, no. 24 ("O

heil’ge Tränen inn'ger

Reue") is a major-key version of the

chorale "Herr lesu

Christ, Du höchstes

Gut" and at the same time an echo of

the Communion liturgy: "...qui

tollis peccata muridi".

The opening and the fugue of no. 25

are evolved from the ‘royal’ theme of

Bach’s A Musical Offering, and

later on the Lutheran hymn "DresdnerAmen"

appears, familiar to today's

music-lover from Mendelssohn's Reformation

Symphony, Wagner's

Parsifal and Bruckner's Ninth.

In the finale, no. 26,

we find at the words "Schedukian's

diamond towers" a reminiscence

of Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony,

whose first performance was given in

Leipzig in 1842.

Moreover, Paradise and the Peri

is of great topical relevance today,

something that is still

underestimated: Schumann and Flechsig

created a story that frees the

spiritual search and fundamental

existential questions from the straitjacket

of Western Christianity

and views them from the distant

perspective of alien cultures and

religions - not unlike the German

writer tessing in his play Nathan

the Wise. In the era of the

Enlightenment, with the Church

gradually playing a smaller role in

bourgeois life, they wanted to arouse

people’s interest in questions of

faith and spiritual issues using the

vehicles of the parable and popular

fairy tales (e.g. the

Peri’s three attempts to gain

admission to Paradise). The exotic

locations add to the work’s appeal,

much as in Mozart's The Magic

Flute, and at the same time

specific symbols supply Christian

connotations, as Hans-Christoph

Becker-Foss has ascertained. Examples

of the latter are the tear that keeps

recurring when the plot takes a

positive turn; the breath that can be

an angel’s breath or the infectious

breath of someone stricken with the

plague; finally, the

recurring references to water and

blood (the Nativity, the Baptism of

Christ, the Last Supper, the

Crucifixion). The

Peri makes it clear to us that Man is

responsible for his own actions. The

willingness to recognize and regret

one’s mistakes, together with love,

goodness, sympathy and devotion,

points the way to salvation: an

irrefutable criticism of all dogmatic

religions, which on the one hand

preach such lessons, but actually

prove the opposite with their actions.

Benjamin-Gunnar

Cohrs, Bremen

2008

Translation:

Clive

Williams, Hamburg

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|