|

1 CD -

82876 60353 2 - (p) 2004

|

|

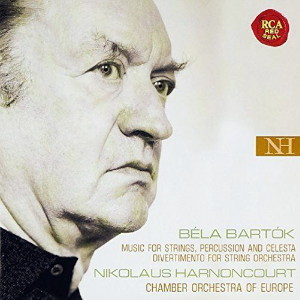

| Béla Bartók

(1881-1945) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Music for Strings, Percussion

and Celesta, Sz. 106 (1936) |

|

33' 04" |

|

| - Andate tranquillo |

9' 10" |

|

1

|

| - Allegro |

7' 49" |

|

2

|

| - Adagio |

8' 05" |

|

3

|

- Allegro molto

|

8' 00" |

|

4

|

| Divertimento for

String Orchestra, Sz. 113 |

|

27' 22" |

|

| - Allegro non troppo |

9' 17" |

|

5

|

| - Molto adagio |

10' 12" |

|

6

|

| - Allegro assai |

7' 53" |

|

7

|

|

|

|

|

| Chamber

Orchestra of Europe |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Stefanienssaal,

Graz (Austria) - 23-26 giugno 2001 (Sz.

106), 23-25 giugno 2000 (Sz. 113) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

studio

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

| Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione CD

|

| RCA

"Red Seal" - 82876 60353 2 - (1 cd) -

60' 26" - (p) 2004 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Music

for Strings, Percussion

and Celesta (1936) and

Divertimento for String

Orchestra (1939)

belong to those charismatic

works by Béla Bartók

(1881-1945) that probably

best embody the Hungarian

composer's contribution to

the music of the 20th

century. They make up a

unique pair. Both are very

personal messages from a

turbulent decade when his

two greatest contemporaries,

Schoenberg and Stravinsky,

had already left Europe. The

one - the Music

for Strings,

Percussion and Celesta

- is often and justly called

Bartók's

chef-d'oeuvre, written in an entirely

personal idiom, a deeply Hungarian yet

universally comprehensible musical

language, at once sublime, at once

magically pagan in tone. It is a

four-movement piece with perfect

proportions, with sensational tirnbres

and stereophonic effects between the

corps of the orchestra. The other -

the Divertimento for

String Orchestra - consists of

three movements and is purely for

strings, a conceivably less attractive

but in fact emotionally more direct

communication unmistakably revealing Bartók's

exuberant feelings just before World

War II broke out. He worked on the

draft score between 2-17 August 1939,

postponing the composition of the slow

middle movement, the darkest vision,

until the end of the very intensive

period. In both cases, Bartók

avoided using the title “symphony".

For the first work, he suggested a

French title, "Musique pour

instruments ŕ cordes, batterie et

célesta, en 4 mouvements"; for the

second his preliminary title was

"Werk/Suite? für Streichorchester",

which he turned to Divertimento when

the draft score was finished.

As is generally known, both scores

were commissioned and premiered by

Paul Sacher and his Basle Chamber

Orchestra, a well-trained group that,

nevertheless, included

non-professional instrumentalists, a

fact that did not disturb Bartók at

all. Lesser known is that he was

already working on a new composition,

the proto-form of Music for

Strings, Percussion and Celesta,

when Sacher's letter reached him.

Originally Bartók was

thinking of a piece for string chamber

orchestra alone. The opening Andante

tranquillo fugue was finished in a

five-part string setting before, from

the second movement on, he switched to

the double string orchestra plus

percussion concept. (A study ofthe

facsimile of the autograph score kept

in the Paul Sacher Stiftung, edited by

Felix Meyer, Schott 2000, offers

an exceptional experience.)

Another peculiarity of the acoustic

concept of Music is the

precise seating plan as Bartók

defined it. It is generally ignored,

however, because it was incorrectly

printed in the score (see the enclosed

facsimile of the plan in Bartók's

handwriting; NB Maestro Harnoncourt

follows faithfully the cornposer’s

concept and makes the most of it). Bartók

positioned the extra instruments on an

axis, thus dividing the left-hand and

right-hand string orchestras, with the

timpani presiding at the top and the

piano at the bottom of the "line of

demarcation." This special

stereophonic conception of the score,

which goes beyond the acoustics and is

part of the semantics of the music,

requires not only left-hand and

right-hand partners in an antiphonal

dialogue, but also a center from where

the quasi judgment comes at major

articulation points of the form.

The concept of Music with its

slow-fast-slow-fast four-movement

design signaled a breakthrough in Bartók's

middle period. After the famous

five-movement or five-part symmetrical

instrumental works with recurring

themes in the first and last and in

the second and fourth parts (String

Quartets Nos. 4 and 5, Piano Concerto

No. 2), here four independent pieces

make up the form: nevertheless,

variants of the initial pianissimo

fugue theme do reappear in the

subsequent movements. This theme

creates the shrill ostinato in the

center of the sonata-form Allegro

second movement; its phrases separate

the A-B-C-B-A sections of the

bridge-form Adagio; finally, extending

the chromatic theme into a diatonic

version, it gives voice to the

hymn-like molto espressivo in the coda

of the Allegro molto finale. Far

beyond the network of thematic links

and other features of strict planning

- including a key plan that uses

tritone relations (a workin A, with E

flat peak in the first movement; the

second and third movements in C and F

sharp, respectively) -, each movement

is an individual masterpiece. And each

of the basic themes, without actual

borrowing, is deeply rooted in

Hungarian folk music: e.g., the

four-line stanza contour of the fugue

theme and its dance-tune variant as

the opening theme of the second

movement; the rhythm and the ornaments

of the Adagio theme; the finale as a

whole, including children’s play song

imitations.

Planning the Divertimento,

months before the actual composition

started - which usually happened

between the instrument and the desk:

improvising at the piano and writing

the draft score -, Bartók

notified Paul Sacher: "I have the

idea... of a kind of concerto grosso

alternating with concertino" (1 July

1939). After Sacher assured him that

adequate players would be available, Bartók,

for the first time, adopted this

neo-baroque texture in his not at all

“neo”-style composition. Incidentally

the number of instrumentalists as

given in the score (at least 6, 6, 4,

4, 2 players) corresponded to the

regular size of the Basle Chamber

Orchestra but Bartók

preferred a larger body: "a complete

string orchestra is naturally even

more suitable." (Harnoncourt’s balance

gives proof of his perfect

understanding of Bartók’s

intentions. Besides, having great

respect forthe Hungarian string

playing traditions, Nikolaus

Harnoncourt achieves wonders in

coaching a Bartók

style, which may be called unique

today, to young musicians.)

The opening theme of the sonata-form

Allegro non troppo, in the key and

meter of baroque pastoral pieces (9/8

in F), but truly in Hungarian

dance-style, is followed by a series

of contrasting themes, reminding one

of the wealth of Mozart’s expositions.

The Allegro assai finale is based on

the 2/4 overt dance variants of the

same themes, in their elaboration

implying tones of the ironic and

humorous, such as pedantic

counterpoint, Gipsy rubato, and a

tipsy episode (a polka) before the

end. The Molto adagio middle movement

belongs to Bartók's

night music topos: a

sorrowful violin melody

followed by a Hungarian

lament, then cries and

shouts, with a return to the

extremely expressive

chromatic melody - one of

the most moving pieces he

was ever to write.

László

Somfai

Director of

the Budapest Bartók

Archives

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|