|

|

Aparté

- 1 CD - AP241 - (p) & (c) 2021

|

|

| Franz Joseph Haydn

(1732-1809) |

Symphony

No. 99 in E flat major, Hob. I:99

(1793) |

|

25' 30" |

|

|

-

Adagio - Vivace assai |

8' 31" |

|

|

|

-

Adagio |

8' 00" |

|

|

|

-

Menuet. Allegretto - Trio |

5' 21" |

|

|

|

-

Finale. Vivace |

4' 38" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Franz Schubert

(1797-1828) |

Symphony

No. 5 B flat major, D 485 (1816) |

|

28' 38" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

7' 14" |

|

|

|

-

Andante con moto |

9' 30" |

|

|

|

-

Menuetto. Allegro molto - Trio |

6' 02" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS

MUSICUS WIEN

- Erich Höbarth (Konzertmeister),

Julia Rubanova, Christian Eisenberger,

Barbara Klebel-Vock, Karl Höffinger, Peter

Schoberwalter, Annelie Gahl, Elisabeth

Stifter, violin 1

- Andrea Bischof,

Theona-Gubba-Chkheidze, Veronica Kröner,

Florian Schönwiese, Silvia Iberer, Editha

Fetz, violin 2

- Firmian Lermer, Dorle Sommer,

Magdalena Fheodoroff, Barbara Konrad,

Florian Hasenburger, viola

- Rudolf Leopold, Dorothea Schönwiese,

Luis Zorita, Ursina Braun, cello

- Brita Bürgschwendtner, Alexandra Dienz,

Jonas Carlsson, double-bass

- Sieglinde Größinger, Reinhard Czasch, flute

- Andreas Helm, Heri Choi, oboe

- Rupert Frankhauser, Georg Riedl, clarinet

- Alberto Grazzi, Ivan Calestani, bassoon

- Dániel Pálkövi, Edward Deskur, horn

- Andreas Lackner, Manuela Tanzer, trumpet

- Sebastian Pauzenberger, timpani

Stefan Gottfried, direction |

|

|

|

|

|

Enregistré |

|

Grande Salle,

Musikverein, Vienna (Austria) -

9-11 ottobre 2020 |

|

|

live / studio |

|

live |

|

|

Direction

artitstique |

|

Nicolas

Bartholomée |

|

|

Prise de son |

|

Nicolas Bartholomée

& Franck Jaffrès

|

|

|

Montage, mixage,

mastering |

|

Franck Jaffrès

|

|

|

Recording system |

|

In

24-bit/96kHz. Microphones DPA 4041

& Schoeps. Recorded and edited

using Merging Technologies

Pyramix. |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Aparté - AP247

- 1 CD - 55' 00" - (p) & (c)

2021 - DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

Recorded by Little

Tribeca.

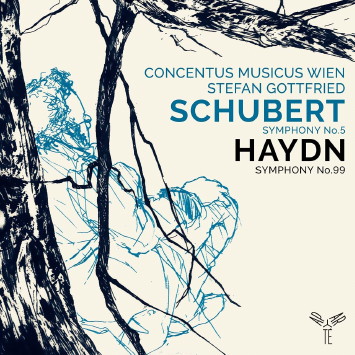

Cover: Detail of the etching Schubert,

sitting underneath a tree,

1997, by Martha Griebler

(1948-2006) by courtesy of the

Estate of Martha Griebler,

represented by Matthias

Griebler.

|

|

|

|

|

Concentus

Musicus Wien continues its

exploration of works of the

Classical and pre-Romantic

periods as envisioned by

Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Stefan

Gottfried conducts Schubert’s

Symphony no. 5, written in

1816 at the age of 19, and the

seventh of Haydn’s 12 London

symphonies, no. 99, written in

1793. The former shows the

melodic inventiveness and

admirable mastery of form of a

young composer, heir to the

giant Haydn. Recorded live at

the famous Musikverein in

Vienna, this concert

immortalises yet again the

skill and the exceptional

sound quality of this renowned

progenitor of historically

informed performance, which

continues to perpetuate the

work of its visionary founder.

····················

The Concentus

Musicus was founded in 1953,

at a time when performance on

period instruments was an

entirely new concept. The

idea, the "spirit" behind

Harnoncourt and the Concentus

I\/lusicus' approach was, and

still is, a constant desire to

find out exactly what the

composer wanted, what sound he

had in his ear when composing,

and what was natural for him

and therefore did not need to

be written down. To this end,

one has to study the

manuscripts carefully, get to

know and understand the sound

and technique of early

instruments, and explore the

original sources on

performance practice. But it

is just as important to forget

all intellectual concerns when

playing, and to create music

out of pure emotion, as if it

were completely new and had

never existed. This

dialectical relationship

between intellect and

emotionality, thinking and

feeling, is needed to do

justice to music and art in

general.

Harnoncourt had also begun to

tackle Franz Schubert's music

with the Concentus Musicus. We

took a further step in this

direction in 2019, with the

recording of Schubert's Unfinished

Symphony, our first by

this composer. This journey,

undertaken with Aparté, was

totally new for us. lt was a

wonderful experience to

capture the magic of

Schubert's music in the unique

acoustics of \/ienna’s Große

Musikvereinsaal. The artistic

and human resonance between

Aparté and the Concentus has

encouraged us to imagine many

joint projects: we naturally

feel a great connection to

Viennese music of the

classical and romantic

periods, but we are still very

much attracted to the Baroque

sound world. This second

recording is therefore another

step on the path we are

following, and we hope that it

reflects the very special

spirit of this orchestra.

Stefan

Gottfried

Interview

by Bertrand Dermoncourt

Franz

Schubert, Symphony no.5

· Joseph Haydn,

Symphony no.99

In an act of homage to

Viennese classicism, the

celebrated ensemble

Concentus Musicus of

Vienna is conducted by

Stefan Gottfried, in a

programme combining the

highly energetic,

colourful Symphony Hob.

I:99 by Joseph Haydn - one

of his 'London Symphonies'

- with the Symphony No. 5

by the young Schubert, a

formally perfect

masterpiece containing a

wealth of melodies, and

overflowing with youthful

vigour.

This unusual coupling -

rather an exception in the

recorded repertoire of

these two composers -

nevertheless has the

advantage of highlighting

certain characteristic

traits of these

symphonies, both in their

similarities and in their

differences. We more often

see Schubert's Fifth

Symphony coupled with

Mozart’s Symphony No. 40,

which it approaches both

in style and in tonality

(Schubert's chosen key of

B flat being the relative

major of the G minor key

of Mozart’s 40th

Symphony), as well as in

aesthetic approach, even

though Mozart's influence

on the young Schubert is

not always obvious (1).

Franz Schubert was still

only nineteen when he

completed the Fifth

Symphony (D.485) in Vienna

in October 1816. lt was

the last of a whole spate

of works composed during

the previous three years

by the prolific teenager.

(2) He was at a turning

point, a halfway milestone

along his symphonic road

between the classical

style and full-blown

romanticism. The imprint

of classicism on

Schubert's writing is

evident here: its

restrained dimensions,

formal simplicity,

adherence to the

accustomed four-movement

structure (including a

minuet), the use of

sophisticated harmonic

progressions, and the

modest orchestral forces

(strings, a flute, two

oboes, two bassoons and

two horns - no clarinets,

trumpets or drums) all

combine to make the work

sound almost like a piece

of chamber music. The

world would have to wait

until 1822 and 1825 for

his major symphonies: No,

7 the 'Unfinished’, and

No. 8, the 'Great' C major

Symphony.

With a vivacity that is

breathtakingly moving, yet

also precise and

perfectly-balanced, the

Allegro first movement in

the classical sonata form

of exposition, development

and recapitulation opens

with a brief three-bar

introduction, then sets

out its two themes: the

first joyful and

confidently combative, the

second more overtly

melodic. Schubert displays

great mastery in the

dialogues he creates

between the timbres of

different instrumental

groups (mainly between

woodwinds and strings).

The second movement, a 6/8

Andante con moto in E flat

major, is tenderly

romantic, with its middle

section's numerous

modulations and

chromaticisms underpinned

by a bass ostinato. As

mentioned earlier, the

Minuet in G minor (with

its Trio in G major) is

particularly akin to the

Mozartian model - it has

the same structure, the

same rhythmic character

even the same harmonic

framework; while the

incredible vitality of the

finale, an Allegro vivace

in sonata form,

impulsively proclaims

Schubert's musical

maturity through its

energy and wide-ranging

palette of sounds: the

manifest talents of a

young composer, though one

who has only twelve years

more to live.

On the death of Nikolaus

l, Prince Esterházy in

1790, Joseph Haydn, who

had been in the service of

this distinguished family

of the Hungarian nobility

as musician and music

director since 1761 - i.e.

for nearly thirty years -

undertook the first major

journey of his life so

far. At the age of

fifty-eight, the composer

travelled to London at the

invitation of the musician

and concert promoter

Johann Peter Salomon, who

had been urging him to

visit for several years.

His first stay in London

in 1791-2 and a second

visit in 1794-5 finally

provided Haydn with the

experience of direct

contact with a public

concert audience. Having

spent so many years at the

Esterházy court, in London

he finally discovered the

outside world, and

experienced a sense of

emancipation. Having been

keenly anticipated, his

arrival caused a

sensation: he was

enthusiastically received,

the press was warm in its

praise for him, and his

works (not only his

symphonies) were widely

performed, enjoying

enormous success. Although

it is one of the twelve

'London symphonies'

performed at his concerts

there (in two groups, Nos.

93-98, and 99-104), the

Symphony No. 99 in E flat

major was actually

composed not in the

English capital, but

between Haydn's two

journeys to England in

1793 in Vienna (or

perhaps, as some

German-language sources

claim, in Eisenstadt), a

period when for six months

he taught counterpoint to

a twenty-two-year-old

musician - a certain

Ludwig van Beethoven.

To inaugurate the second

set of Haydn's London

concerts, this symphony

was first performed at the

Hanover Square Rooms, the

city's main concert hall,

on 10 February 1794. After

a slow introduction, the

generously-proportioned

and expressive first

movement sets out two

contrasting themes that

are developed and then

restated in the apotheosis

of the final section. The

Adagio that follows is one

of the composer's finest

slow movements, toying

playfully with sonorities,

the end of the first

thematic phrase being

echoed by the flutes and

oboes, with a superb

passage for solo winds

(flutes, oboes and

clarinets) and even a

brass fanfare in the final

bars. The various themes

heard in the exposition

are developed with a sense

of high drama, then

restated in a completely

new orchestration. The

exultant, turbulent Minuet

in E flat is set off

against the central Trio

in C major, which hasthe

rather more discreet

elegance of a typical

Viennese waltz. The work

ends with a Vivace in the

sonata rondo form which

Haydn frequently favoured

- this one having a

refrain with three

episodes. (The entire

sketches for this movement

have been found,

containing around thirty

different thematic ideas,

all numbered.) The

movements three verses

correspond to the three

main parts of a sonata

structure; an exposition,

a development of great

contrapuntal density with

a fugato section (another

typical Haydn fingerprint)

and a recapitulation, Here

too, Haydn unfurls

brilliant passages

dominated by the winds,

particularly the

woodwinds, before the

final flourish.

This symphony shows a

certain relationship with

Mozart. Significantly

enough, when Haydn

composed it his friend

Mozart's death was still

quite recent; and although

in many respects the

differences in style of

the two composers are

undeniable, Haydn's 99th

has a remarkably close

proximity to the 'Mozart

sound', beginning with

Haydn's inclusion of the

clarinet. This is the

first of Haydn's

symphonies to use its

bright timbre, and here

the clarinet is heard in

company with the trumpets

and drums that are

themselves sufficiently

rare in Haydn’s symphonies

to be worth noting. These

three instruments are

notably absent from

Schubert's Symphony No. 5,

so with this coupling the

Concentus Musicus Wien is

drawing attention to the

two contrasting choices of

composers breaking with

their usual custom:

Schubert dispensing with

three typical instruments

of the symphonic

orchestral line-up that

Haydn - exceptionally for

him - here decides to use.

(3) On the other hand,

Haydn's opening Adagio

introduction, with its

dramatic ending on the

dominant of C minor

preceded by enharmonically

chromatic modulations, is

a definite reminder of

Mozart's 40th Symphony -

as is the lyric vein

cultivated by Haydn,

particularly in his second

movement. Was this work

then perhaps an elegiac

homage to his lamented

young friend? Yet Mozart

is not the only point of

connection between the

symphonies of Haydn and

those of Schubert.

By the year 1816, Schubert

was already extremely

familiar with this grand

symphonic repertoire: as a

scholarship boy (from 1808

to 1813) of the

prestigious Stadtkonvikt

school in Vienna he had

played in the college

orchestra that regularly

performed the symphonies

of both Mozart and Haydn.

Given that background, the

similarities between the

two works in this

recording emerge more

clearly: the chromaticism

so notably evident in the

slow movements of both

symphonies (also in the

first movement of the

Schubert) and the rich

string textures of both

opening movements are

underpinned in each case

by syncopations in the

internal voices. ln a more

allusive way, the

playfulness of Schubert's

finale recalls the first

movement of the elder

composer's Symphony No.

99, while its freshness

and directness of

expression evokes the

character of Haydn's

sonata rondo finales, such

as that of the 99th.

Conversely, it is tempting

to hear echoes in Haydn of

what is to become a marked

stylistic trait in

Schubert: the brusque

change from major to minor

(or vice versa, the sudden

'dramatic major key' being

almost more tragic than

the minor). ln this light

the central and final

sections ot Haydn's second

movement are particularly

evocative.

Haydn's 99th is considered

one of his most deeply

expressive symphonies:

despite being always

elegant and witty, it has

many dramatic breakthrough

moments which are all the

more poignant because of

their contrast.The

parallels between Haydn

and Schubert manifested by

this recording are a rare

opportunity to highlight

their points of

similarity, less in terms

of a proximity of

technique than in their

undeniably strong

expressive links, and

their shared mode of

feeling.

Gabrielle

Oliveira Guyon

(1) Actually Schubert was

highly influenced by

Mozart's music,

particularly by his 40th

Symphony. There are not

only the obvious

similarities (particularly

in the Minuets of both

symphonies as well as the

first movement’s opening,

its tempo and general

thematic plan), but also

the many influences of

phrase structure,

chromaticism, and melodic

style. These affinities

seem even more real now

than they did in 1816, the

year Schubert composed

this Symphony, writing in

his journal: 'Today will

remain with me for the

rest of my life, a clear,

brilliant, beautiful day.

How sweetly through the

distance of memory sound

the enchanted notes of

Mozart's music! [...]

These exquisite

impressions that neither

time nor circumstance can

erase, remain in our soul

and have a salutary effect

on our very existence.

[...] Mozart, immortal

Mozart, how many, how

infinitely many benign

impressions of a brighter,

better life do you imprint

in our souls!' [* voir

note 1A, du Trad]

(2) From this period we

have Schubert works of

every genre, including

around two hundred Lieder,

two settings of the Stabat

Mater, several piano

sonatas and four Masses.

(3) ln the Haydn period,

the clarinet was not yet a

standard instrument of the

symphony orchestra, and

did not become so until

Beethoven.

|

|

|