|

2 DVD

- 003.2011 - (c) 2011

|

|

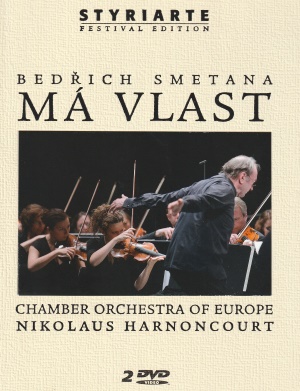

Bedřich Smetana

(1824-1884)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ma vlast (My

Fatherland) - Cicle of Symphonic Poems |

94' 00" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Višehrad |

|

|

DVD1-1 |

| - Vltava (The Moldau) |

|

|

DVD1-2 |

| - Šárka |

|

|

DVD1-3

|

| - Z českých luhů a hájů (from Bohemia's Fields

and Groves) |

|

|

DVD1-4

|

| - Tábor |

|

|

DVD1-5

|

| - Blaník |

|

|

DVD1-6

|

|

|

|

|

| BONUS: Making of "Má

vlast" - A documentary by Günter

Schilhan |

67' 00" |

|

DVD2

|

|

|

|

|

Chamber Orchestra

of Europe

|

|

| Lorenza

Borrani, Violin (concert master) |

Luis

Zorita, Violoncello |

|

| Sophie

Besançon, Violin |

Enno

Senft, Kontrabass |

|

| Christian

Eisenberger, Violin |

Denton

Roberts, Kontrabass |

|

| Lucy

Gould, Violin |

Lutz

Schumacher, Kontrabass |

|

| Meesun

Hong, Violin |

Magali

Mosner, Flute |

|

| Ulrika

Jansson, Violin |

Josine

Buter, Flute |

|

| Matilda

Kaul, Violin |

Ricardo

Borrull, Flute |

|

| Sylwia

Konopka, Violin |

Giorgi

Gvantseladze, Oboe |

|

| Elissa

Lee, Violin |

Rachel

Frost, Oboe |

|

| Stefano

Mollo, Violin |

Romain

Guyot, Clarinet |

|

| Peter

Olofsson, Violin |

Manuel

Metzger, Clarinet |

|

| Fredrik

Paulsson, Violin |

Ole

Kristian Dahl, Bassoon |

|

| Joseph

Rappaport, Violin |

Christopher

Gunia, Bassoon |

|

| Nina

Reddig, Violin |

Peter

Francomb, Horn |

|

| Håkan

Rudner, Violin |

Elizabeth

Randell, Horn |

|

| Aki

Saulière, Violin |

Jan

Harshagen, Horn |

|

| Lisa

Schatzman, Violin |

Peter

Richards, Horn |

|

| Gabrielle

Shek, Violin |

David

Tollington, Horn |

|

| Martin

Walch, Violin |

Nicholas

Thompson, Trumpet |

|

| Pascal

Siffert, Viola |

Julian

Poore, Trumpet |

|

| Gert-Inge

Andersson, Viola |

Paul

Sharp, Trumpet |

|

| Ida

Speyer Grøn, Viola |

Håkan

Björkman, Trombone |

|

| Claudia

Hofert, Viola |

Nicholas

Eastop, Trombone |

|

| Simone

Jandl, Viola |

Jen

Bjợrn-Larsen, Tuba |

|

| Riika

Repo, Viola |

Dieter

Seiler, Timpani |

|

| Dorle

Sommer, Viola |

David

Jackson, Percussion |

|

| Howard

Penny, Violoncello |

Daniel

Piedl, Percussion |

|

| Rafaeil

Bell, Violoncello |

Brian

Lewis, Harp |

|

| Luise

Buchberger, Violoncello |

Gabriella

Dall'Olio, Harp |

|

| Tomas

Djupsjöbacka, Violoncello |

|

|

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Conductor

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Helmut-List-Halle, Graz

(Austria) - giugno 2010 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Steirische

Kulturveranstaltungen GmbH |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

-

|

Prima

Edizione DVD

|

| Styriarte - 001.2011 -

(2 DVD) - 94' 00" + 67' 00" - (c) 2011 -

NTSC - Stereo |

|

|

AD NOTAM

|

Countless

honorary titles have been bestowed upon

Bedřich Smetana’s cycle of

symphonic poems, Má

vlast. It has

been referred to as a reflection of the

Czech people’s past, their present and

their future and compared to the Song

of Solomon as a kind of Song

of Songs sung from the very soul

of a national people. Regardless of how

such monikers may be interpreted, they

can only paraphrase the unique

fascination these six poems have

inspired since their premiere in 1882.

MÁ

VLAST

FROM 1939 TO 1990

During Nazi occupation in

the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia,

programme authors were forbidden to

write more than one line explaining the

various symphonic poems making up

Smetana’s Má vlast. Anyone brave

enouvh to go into more

detail aid a heavy price. One such man

was Zdenĕk Nĕmec,

a music critic from Prague who was so

inspired by a performance of Má vlast

that he afterwards wrote of victorious

knights who would “arrive in the

Nation’s hour of need to break the bonds

of oppression and darkness.” Soon

afterwards Némec was arrested

by the Gestapo and “beaten to death like

a mangy dog because he dared to reveal

the hope which

Smetana had concealed in Má vlast

for every Czech to find” (Linda Maria

Koldau).

A few months before Némec’s

brutal murder, prisoners in the

concentration camp at Mauthausen near

Linz had the rare opportunity to

experience this same hope while

listening to a performance of Smetana’s

music. The SS camp commanders allowed a

commemorative celebration marking

Smetana’s 120th birthday

and the 60th anniversary

of his death and even allowed the camp

orchestra to put candles on their music

stands. “Within the

camp the prisoners were all just numbers

and the SS could extinguish each and

every one of them easier than the

candles flickering on the music stands,

but the splendour of this Smetana

celebration left even these tormented

souls speechless; tears flowed freely

down their sunken faces as the

orchestra, conducted by Rumbauer, played

the overture to Smetana’s The Kiss,

followed by a potpourri from The

Bartered Bride and finally rounded

off with Vltava. The celebration

was more than a success; it was a

manifestation of humanity and of an

unbreakable love for one’s homeland”

(Milan Kuna, Musik an der Grenze des

Lebens).

Whenever the Czech nation has been in

need of a symbol of her unity and her

will to survive, she has reached out for

Má vlast.

Smetana’s cycle of symphonic poems gave

the nation hope while under Austrian

rule in World War I,

throughout German occupation in World

War II and during and after the Velvet

Revolution of 1989/90. “During times of

vicious persecution, when politicians

were left unable to make any public

declarations and forms of artistic

expression, especially literature, were

fettered and constrained, Smetana’s

music was able to evade vigilant censors

who considered it to be merely a piece

of musical art. The poems, which thus

resounded as the only genuine, free

expression of the people’s sentiments,

garnered broad acclaim as more than just

something artistic and musical - so much

so that the Austrian authorities

eventually began to view Má

vlast as

something suspicious and treasonable”

(Zdenĕk Nejedlý,

1924).

Nikolaus Harnoncourt remembers the

legendary performance of Má

vlast conducted

by Rafael Kubelik at the opening of the

Prague Spring Festival in 1990, only a

few months after the fall of communism.

“I know that Rafael Kubelik -

really one of the nicest conductors I

have ever met -

conducted Má vlast just

as Czechoslovakia had shed itself of the

communist yoke. He returned to conduct

his Czech Philharmonic in honour of this

political occasion. The music of Má

vlast was so

much a part of him that he never even

needed the score. He conducted the

entire piece from memory, although he

hadn’t performed it in years. He came

back and conducted it as though it was

something he had done every day of his

life”, recalls Harnoncourt. Kubelik had

previously conducted Má

vlast on 12

May 1946, the anniversary of Smetana’s

death, which was the first performance

of the piece in Prague after the

liberation from German occupation. Since

then, every Prague Spring Festival

commences with a performance of

Smetana’s symphonic poems. Extracts of

the piece are also found in Czech

day-to-day life, with the Czech

broadcasting company using Vyšehrad

as an interval signal and the bells of

the Basilica of St Peter and St Paul

chiming the melody to Vltava.

MÁ

VLAST - A RARITY

While conducting some of

the world’s most renowned orchestras,

Nikolaus Harnoncourt has come to realize

that Má vlast played in its

entirety is not a familiar piece for

many. It is performed so seldom that it

is in little danger of becoming kitsch.

“When I was conducting the piece in

Holland, it was the first time the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra had performed it

in twenty years,” he remembers. “They

were completely surprised. Some former

orchestra members were there and said

they had played it twenty years before

with Dorati. And the Vienna Philharmonic

hadn’t performed the entire piece since

James Levine’s day,

which had been many years before - where

is the kitsch in that? It is actually

not a sunny piece at all but rather a

veiled horror. Even From Bohemia's

woods and fields is a bit

horrific. It starts with a sunny

atmosphere but then you start to ask

yourself, ‘Is this really beautiful?'

It’s always interrupted with something

horrific. I suppose Vltava could

probably be made kitschy but I would

never even think of finding the piece

itself kitschy. There is something

sublime about it but that is quite

natural, the sense of home it evokes. I

don't know whether there is a country or

a people or ethnic group anywhere in the

world, be they ever so small, which does

not develop a certain enthusiasm for its

own uniqueness. I think that this

feeling exists everywhere, from the

smallest to the largest cultural

groups.”

Harnoncourt goes on to remark that “as

far as the tone painting is concerned,

there is nothing superficial or kitschy

about the piece. Ok, the scenes in Vltava

with the nymphs and the dancing are

quite clear and obvious. But Šárka

is a complicated story. Do we really

know what she is discussing with her

maidens? She calls out for help and the

knights arrive, and then she summons her

maidens with a hunting horn and they

come armed with weapons and in the end

she regrets that it is too late to

prevent the massacre. The men lie drunk

out of their wits on the ground and are

butchered, all the men of Bohemia.”

“I spent quite a lot of time researching

and talking to Czech people and reading

everything I could find about the piece

including material on the stories

surrounding Tábor and

Blaník. To understand them

you have to understand the Hussite

chorale, the entire Hussite movement,

what they stood for and what they

opposed, that the Hussite knights, with

their strong faith, disappeared into a

mountain to await the time when they

would awaken to rescue the entire world.

The ‘entire world’ here being Bohemia.”

HISTORY,

STORIES, PROGRAMME

Smetana composed his six

symphonic poems in just under five

years. At first it seemed he would

confine his piece to a tetralogy. Vyšehrad

and Vltava were completed

towards the end of 1874 and Šárka,

and From Bohemia's woods and

fields in the autumn

of 1875. It was not until 1878 that

Smetana resumed his work and composed Tábor

and Blaník,

which he completed in just a few months.

These two pieces were based on the

images of resistance and triumph which

unfurl in the Hussite chorale. The motif

found in Vyšehrad serves

as the piece’s motto as it is a

recurring theme throughout the entire

cycle, making itself known in Vltava

and at the end of Blaník.

On 5 November 1882, Má vlast

was performed in Prague in its entirety

for the first time and

frantically celebrated as a resounding

symbol of the nation. Otakar Hostinský

wrote of the performance: “After Vltava,

a real hurricane of excitement broke

loose ... and the same storm of applause

was repeated after each of the six parts

of the cycle. The audience listened with

growing enthusiasm up to the very last

chord ... After the clashing sounds in Blaník,

the listeners were beside themselves and

couldn’t bring themselves to take leave

of Smetana, who, though he had not been

able to hear a single note of his own

work, was still pleased to know that he

had delighted others.” Smetana, who had

been completely deaf since the completion

of Vltava in 1874, was never

able to listen to his most famous work

in its entirety. His enthusiasm for the

material he dealt with in his music,

however, never waned. Bohemia was slowly

breaking away from Vienna’s paternalism

and starting to emerge as a confident

nation and Smetana wanted to give his

fellow Czechs a musical apotheosis of

their most important myths and beautiful

landscape.

Smetana’s musical landscape painting is

also understandable for listeners

outside of Czechia, which is why Vltava

and From Bohemia's woods and fields

have become the cycle’s most popular

pieces with international audiences. The

remaining four symphonic poems, however,

elude listeners not familiar with

Bohemia’s history. For hundreds of

years, the ruins of a powerful

stronghold loomed atop Vyšehrad,

a steep rock towering over the Vltava

river and which today makes up part of

the city of Prague. It was a monument to

the erstwhile greatness of medieval

Czech rulers, who had been displaced by

the House of Habsburg. The bloody story

of Šárka

belongs to the saga surrounding the Maidens’

War; the gruesome war between

women warriors led by Vlasta against

male knights. The city of Tábor

in Southern Bohemia was founded in 1420

by a radical group of Hussites,

forerunners of the protestant movement

in Bohemia and who followed the

teachings of Jan Hus.

These men believed themselves to be holy

warriors but were eventually defeated by

the imperial army and the moderate

Bohemians. It is this event that Smetana

interprets in Tábor,

which leans on the Hussite chorale Ye

Who Are The Warriors Of God. He

makes use of this same material once

more in the incomparably ecstatic finale

of Blaník, named after a

mountain not far from Tábor.

According to legend, Blaník

is the resting place of the defeated

Hussite knights, who, in the nation’s

greatest hour of need, will once more

ride forth to her aid.

Each of the six pieces has two official

programmes. The first is a short

programme which was written

by Smetana himself and sent to his

publisher, Urbánek, in

1879. The second, which quotes and

explains short passages from the

original, is more detailed. Václav

Zelený published this second,

poetically embellished programme in the

periodical Dalibor in 1882 with

the composer’s consent.

Josef

Beheimb

(Translation: Melissa

Kercher)

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|