|

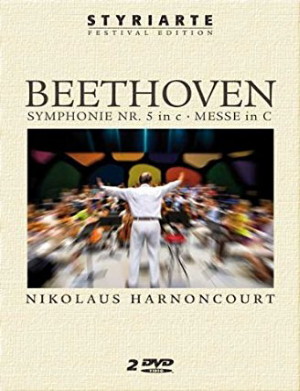

2 DVD

- 002.2010 - (c) 2010

|

|

Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Messe in C-Dur, Op. 86 |

51' 00" |

|

DVD1

|

| - Gloria (Allegro con brio) |

|

|

|

| - Credo (Allegro con brio) |

|

|

|

| - Sanctus (Adagio) |

|

|

|

| - Benedictus (Allegretto

ma non troppo) |

|

|

|

| - Agnus Dei (Poco andante) |

|

|

|

| Symphonie Nr. 5 in

C-moll, Op. 67 |

37' 00" |

|

DVD1

|

| - Allegro con brio |

|

|

|

| - Andante con moto |

|

|

|

| - Allegro |

|

|

|

| - Allegro Presto |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BONUS: "Making of

Beethoven!" - A documentary by Günter

Schilhan |

73' 00" |

|

DVD2

|

|

|

|

|

Julia Kleiter,

Soprano

|

|

Elisabeth von

Magnus, Alto

|

|

Herbert Lippert,

Tenot

|

|

Geert Smits,

Bass

|

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

master |

|

|

|

Chamber Orchestra

of Europe

|

|

| Marieke

Blankestijn, Violin (concert

master) |

Kate

Gould, Violoncello |

|

| Sophie

Besançon, Violin |

Sally

Jane Pendlebury, Violoncello |

|

| Fiona

Brett, Violin |

Howard

Penny, Violoncello |

|

| Christian

Eisenberger, Violin |

Enno

Senft, Kontrabass |

|

| Ulf

Forsberg, Violin |

Denton

Roberts, Kontrabass |

|

| Lucy

Gould, Violin |

Lutz

Schumacher, Kontrabass |

|

| Iris

Juda, Violin |

Eline

van Esche, Flute |

|

| Matilda

Kaul, Violin |

Josine

Buter, Flute |

|

| Birgit

Kolar, Violin |

Magdalena

Martinez, Piccolo |

|

| Sylwia

Konopka, Violin |

Giorgi

Gvantseladze, Oboe |

|

| Maria

Kubizek, Violin |

Rachel

Frost, Oboe |

|

| Elissa

Lee, Violin |

Martin

Spangenberg, Clarinet |

|

| Stefano

Mollo, Violin |

Marie

Lloyd, Clarinet |

|

| Frederik

Paulsson, Violin |

Matthew

Wilkie, Bassoon |

|

| Joseph

Rappaport, Violin |

Christopher

Gunia, Bassoon |

|

| Nina

Reddig, Violin |

Ulrich

Kircheis, Contrabassoon |

|

| Aki

Sauliere, Violin |

Jonathan

Williams, Horn |

|

| Henriette

Scheytt, Violin |

Jan

Harshagen, Horn |

|

| Martin

Walch, Violin |

Peter

Richards, Horn |

|

| Mats

Zetterqvist, Violin |

Josef

Sterlinger, Horn |

|

| Pascal

Siffert, Viola |

Nicholas

Thompson, Trumpet |

|

| Gert-Inge

Andersson, Viola |

Julian

Poore, Trumpet |

|

| Stewart

Eaton, Viola |

Christopher

Dicken, Trumpet |

|

| Ida

Grøn, Viola |

Håkan

Bjorkman, Trombone |

|

| Dorle

Sommer, Viola |

Karl

Frisendahl, Trombone |

|

| Stephen

Wright, Viola |

Nicholas

Eastop, Bass trombone |

|

| William

Conway, Violoncello |

Geoffrey

Prentice, Timpani |

|

| Tomas

Djupsjöbacka, Violoncello |

|

|

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

Helmut-List-Halle, Graz

(Austria) - giugno 2007

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

Steierische

Kulturveranstaltungen GmbH

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

-

|

Prima

Edizione DVD

|

Styriarte - 002.2010 -

(2 dvd) - 88' 00" + 73' 00" - (c) 2010 -

NTSC - Stereo

|

|

|

AD NOTAM

|

Mass

in C Major, Op. 86

"But dear

Beethoven, what is it you have done

here?" Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy

asked the composer after the premiere of

Mass in C Major. The prince had

commissioned Beethoven to follow in Haydn’s

footsteps and create a mass in

celebration of his wife Princess Maria

Hermenegild’s name day. What the prince

received, however, was neither obedient,

courtly music of celebration, nor was it

a continuation of Haydn’s tradition.

Beethoven had defied so many musical

conventions even with the opening notes

of this Ordinary of the Mass that the

tradition-conscious listeners at the

court in Eisenstadt completely turned up

their noses at the piece. Even ten years

later, the Allgemeine musikalische

Zeiung declared that the piece had

abandoned what had been considered

sacred style for centuries. Beethoven

had broken new ground and it was this

which drew the prince’s arrogant

comment. The maestro answered by

promptly departing and refused to

dedicate the piece to the prince. When

his Mass in C Major was

finally published as Opus 86 in

1812, it was dedicated to Prince Kinsky.

Beethoven wrote to the Breitkopf

publishing company, “I do not like to

speak of my mass, much less of myself,

but I do believe that few others have

approached the text as I have,” showing

that he was well aware he had

interpreted the Ordinary of the Mass

in a new fashion. Newspapers of the

time, attempting to grasp this

innovation in words, referred to it as a

“noble approach in which only that which

is holy manifests itself.”

Beethoven had indeed radically distanced

himself from the conventions of the

classical cantata mass, conventions

which Haydn and Mozart before him had

considered obligatory. The maestro had

chosen to exclude conventional arias and

virtuosic displays by the soloists as

well as concerto-like pomp in the

orchestra. The resulting piece is

symphonic, in the truest meaning of the

term, with an organic consonance aimed

only at attaining that which is holy.

“To come ever nearer to the divine in

order to inspire its radiance in mankind

- there is nothing more

noble,” wrote Beethoven in his diary. What

he meant by divine however was

not so much the festively celebrated God

of the Catholic Church but rather

the everlastin and transcendental

creator, whose manifestation is visible

in the natural world, Beethoven's

desire to compose his music in honour of

that which is all-powerful,

everlasting and without end had two

consequences for his Mass in C Major.

Firstly,

emotion replaces representation and,

secondly, instead of outward pomp,

we hear an emphasis more exceptional

than any other, an emphasis which

stretches past the four corners of the

earth to reach the eternal.

In order to ensure the simplicity of the

holy, Beethoven drew on an archaic

stylistic device, syllabic declamation.

There are virtually no melismas in the

choral sections of the Mass, with the

exception of the great concluding

fugues. Syllable by syllable and in

emphatic simplicity, the text is

declaimed in simple note values. This is

especially true in both of the longer

movements, Gloria and Credo.

All tone painting, every element that

depicts and paints, is created by the

orchestra, if at all. The instruments

often participate in the declamation,

lending themselves as one more voice in

an old-style counterpoint with even the

soloists adapting themselves to this

ideal. Arnold Schmitz wrote, “One would

search in vain, not only in contemporary

productions of average merit but also in

those of Mozart and both Haydns, for

accompaniment of this kind, which

follows the meaning and diction of the

liturgy.”

In his analysis of the piece, the

composer, critic and poet, E.T.A.

Hoffmann, describes the expression that

is created as that of childlike emotion,

which stands in contradiction to the

expected. As he writes, “Beethoven’s

genius sets in motion the lever of awe,

of horror. In this way, the critic

believes, viewing the supernatural would

also fill the soul with fear and that he

could express this feeling in notes.

However, what is created is an

expression of a childlike, mirthful soul

- a soul which, thanks to its purity,

believes in the mercy of God and cries

to him, as to a father who wants the

best for his children and hears their

pleas.” What Hoffmann neglects to

mention are the virtually insatiable,

expansive moments in the piece. The Sturm

und Drang produced in the presence

of the Almighty in the Mass in C

Major closely resembles examples

in the Missa Solemnis.

Regarding the individual movements of

the piece, the Mass begins, without any

overture, with a Kyrie

by the basses. The descant voices

intonate over them with a “sweet theme”,

which, as Hoffmann states, is the

“prayer of a child confident in mercy

and fulfilment.” The theme’s arch

blossoms in a rapid crescendo and is

then superseded by a second contrapuntal

theme from the soloists, which soon

leads off into a sombre minor. The Christe,

a short, intimate a cappella quartet by

the soloists, brings the piece back

around to the major. Beethoven

researcher Joseph Kerman

observed one and the same emotional

curve six times within this one

movement, calling it a murmur leading to

an expectant back and forth, followed by

a fearful plea. It is not until the end

that the tension is released in a chain

of wonderfully suspended chords.

The choir’s Gloria begins

attacca and without any lead in. It

is wild, an outcry, with the violins

striving rapidly heavenward, Ini

excelsis Deo. This beginning

stands in stark contrast to the quiet Et

in terra

pax, a nearly halting song of

supplication. The Laudamus,

however, takes up the Gloria's

ecstatic style once more. Beethoven

entrusted the solo tenor with the

simplest declamation of the Gratias

agimus. Like a precentor at mass,

the choir answers him in interjections.

The Qui tollis is dominated by

anxious melodics, an alto solo in F

minor, which is accentuated by the

strings' sighs, the

choir’s pleading misereres and finally,

by the four soloists. The Quouiam

is, as Hoffmann puts it, a “rather

jubilant unison” and the Cum sancto

spiritu is a

completely free, powerfully escalating

fugue.

Hoffmann found the Credo to be a

living, fiery movement, whose manifold

imitations emerge in a well-ordered,

delightful manner. It is much more than

just that, however. It is a moment of

awe in the presence of God, a mysterious

ripple that escalates rapidly towards

fortissimo. Ecstasy seizes the entire

ensemble, the string figure rolls upward

and the choir sharply chants the lines

of the creed. A brief clarinet solo

segues into the Incarnatus,

a quartet of soloists sung over plucked

strings, folk-like in its simplicity.

The choir’s sombre declamation of the Crucifixus

is answered by the soloists with the

utmost trepidation in the Passus et

sepultus est. Hoffmann describes

the movement as enacted in a muffled

manner in which the bass solo elevates

the Et resurrexit in common

time. He goes on to praise the movement

as vigorous and ingenious, with

alternating tutti and solos as well as

manifold imitations, which bear witness

to the maestro’s imagination.

Furthermore, Hoffmann declares the

appearance of the Et vitam

a jubilant fugue theme.

The beginning of Beethoven’s Sanctus,

much like Schubert’s later version, is

immersed in mysterious, pianissimo

notes. Schmitz claimed the silence of

eternity could be heard more clearly

here than in the line “Can you sense

your creator?” in the finale of

Beethoven`s Symphony No. 9. Hoffmann

describes this movement as gentle and

stirring, thanks in part to the

instrumental atmosphere created by the

oboes, A clarinets, middle string

instruments and bassoons. The four

soloists start the Benedictus

unaccompanied. This is yet

another simple song of thanks to heaven,

which is later taken up by the choir. In

1815, one critic wrote that the soul

dwells in the Benedictus

quartet, immersed in the glory of the

eternal with the continual recurrence of

the theme in every harmonic composition.

The same critic goes on to describe the

segue between the pious song of

supplication, Agnus Dei, into

the Dona nobis

pacem, full of solace and delight,

as being of indescribable impact. The Agnus

Dei’s triplet bebungs in sombre C

minor set up the choir’s pleas. In the Dona

nobis pacem, they pass over into a

radiant C major, a per aspera ad

astra, which corresponds to the

segue between the scherzo and the finale

in the fifth. The simple, sober music of

the Kyrie returns here at the

end to round up the mass.

In regards to the

piece’s impact, E.T.A. Hoffmann wrote

that the tempos are not overhasty, as

had unfortunately become the custom at

the time, and that the singers and

musicians endeavour to do justice to

this ingenious piece by adhering exactly

to the piano and the forte as well as

all other forms of expression. Thus, not

only the connoisseur is lifted up and

affected but also the listener who is

unable to delve into the actual essence

of the piece.

Symphony

No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67

It is understandable that

a work as popular as Beethoven’s Symphony

No. 5 should be entwined with

anecdotes. One of these is particularly

characteristic of the piece: Beethoven’s

triumphant C major tones so compellingly

suggested the heroic figure of Emperor

Napoleon, that a veteran of the Grand

Armée jumped up after just the

first bars had been played and called

out, “C’est l’empereur! Vive

l’empereur!”.

Beethoven, however, very unlikely sought

to create a political association of

that kind. In fact, in 1808,

as Vienna was threatened by war,

Beethoven aligned himself with those who

stood against the Emperor. The great per

aspera ad astra of

Beethoven’s Symphony in C minor

does suggest a heroic battle and

perseverance in the face of fate, but on

a very general level, not affiliated

with the warring parties. And yet, the

Symphony is a piece of combative vigour,

an expression of Beethoven’s wish to

understand military strategy as well as

he understood the art of composing. He

was convinced that were this the case,

he could certainly defeat the French

emperor.

Napoleon and his Grand Armée

have the Symphony No. 5 to thank

at least for their emotional appeal as

Beethoven concretely borrows from the

French revolutionaries’ songs for his

piece. The throbbing rhythm at the

beginning of the piece was inspired by

Cherubini’s Hymne dn Panthéon,

with the heroic oath, “We swear, with

iron in our hands, to die for the

Republic and the rights of mankind.” The

music of the revolution’s aesthetic

ideal, namely the elan terrible

and éclat

triumphal,

are classically manifested in Symphony

No. 5.

The first movement is the most extreme

execution of elan terrible

imaginable. It is unrelenting in its

development of the famous opening motif

charging ahead almost without caesura

and with only a scarce idyll in the

secondary theme, which is accompanied by

an unsettling basic rhythm. When

confronted with the manner in which this

movement unrelentingly charges ahead,

Wilhelm Furtwängler

once asked himself how Beethoven could

be considered a classical composer, “It

is made up of just the driest facts, no

ambiance. Is that a classical composer?

At any rate, not a romantic one. It has

nothing to do with these historical

terms. It is the sculptor, or better

yet, the dramatist who speaks here. It

is all development, everything is

portrayed at the moment it is acted

out”.

Even the flowing andante con moto

of the second movement, with the cellos’

stirring notes in A flat major, is

interrupted by the brute force fanfare

of military music, creating a triumphant

episode which detaches itself from the

main theme in unrestricted variations.

If the Symphony’s climax and ultimate

objective is the segue between the

sombre C minor into the radiant C major,

then Beethoven’s segue in the scherzo

and finale is consummate. The musical

path starts with the tentative beginning

of the scherzo and continues on to the

theme’s blaring horns, finally arriving

at the overwhelming escalation just

before the break through to C major,

with this immense arc of tension being

interrupted by the contrapuntal trio. In

the finale, Beethoven summons all the

sounds of the éclat

triumphal: vibrant trumpets,

blaring horns, trombones and piccolos

and a constant wave of string and

woodwind instruments. There is no

differentiation of expression here.

Rather, the nervous emphasis of victory

and the insatiableness of apotheosis

reign supreme here - until the notorious

conclusion that can find no end.

Josef Beheimb

(Translation: Fiona

Begley)

At the first rehearsal in the

Helmut-List-Halle in Graz, Nikolaus

Harnoncourt surprised the Chamber

Orchestra of Europe with his own

insights into the Fifth Symphony,

which was completed at about the same

time as the Mass in C Major.

“In the preparation for this concert, I

found out two things: The Mass and the

Symphony were composed simultaneously.

Whenever Beethoven got in the wild mood

of the Symphony, he composed the

Symphony, and when ideas of piety and

smoothness came up to him, he shifted to

the other table in order to compose the

Mass. I think this is very interesting

for the programme, you can feel the

connection. But until one week ago, I

did not know what the Symphony really

means.

Now, I am convinced that the first

movement of the Symphony shows how a

population is depressed because of

dictatorship: everybody is afraid, every

justice is injustice, people have been

imprisoned, and nobody knows why. So it

is maybe a pre-revolution situation, the

main point being that there is no

justice. The famous beginning means

people in chains who want to free

themselves. This goes through the whole

piece. There is a great revolutionary

energy in the work, not a victorious

energy, but the energy of the oppressed.

The second subject is like a vision of

light: How could it be if we all were

free? The main part of the first

movement is really

bold.

The second movement - I am sure - means

a prayer. Here in Graz, I was a boy

during Nazi time, and it was not really

allowed for us to go to church. So, to

go there was a prayer of the believing

part of the population who prayed: "Please,

God, free us from that oppression."

That is what Beethoven meant with the

first subject of the second movement. In

the middle sections of the variation

movement you can hear the others who do

not believe in God: Your prayer is for

nothing. We have to take our guns and

free ourselves from oppression without

God’s help!

The third movement is a revolution of

the students who are very idealistic,

but not very effective. In the trios we

hear the students with their student

song, in the main part the real

population who say: Wait! That is what

the beginning of the movement tells us.

"Let us wait for the

right moment." In the

great repetition it is the story of the

act of liberation.

What does the end of the Symphony mean,

when the trombones, the piccolo flute

and the double bassoon come in? It is

open air music, it has something to do

with agitation. It is victorious,

triumphant music: Now, we have won!"

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|