|

|

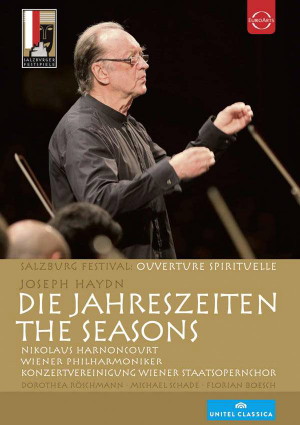

1 DVD

- 2072678 - (c) 2014

|

|

| SALSBURG FESTIVAL 2013 -

Ouverture Spirituelle |

|

|

|

|

|

| Franz Joseph Haydn

(1732-1809) |

|

|

| Die Jahreszeiten |

140' 26" |

|

| - Der Frühling |

33' 14" |

|

| - Der Sommer |

38' 39" |

|

| - Der Herbst |

35' 45"

|

|

| - Der Winter |

32' 48" |

|

|

|

|

BONUS: "Nikolaus

Harnoncourt rehearsing Joseph Haydn's

The Seasons" by Eric Schulz

|

28' 06" |

|

|

|

|

| Dorothea

Röschmann,

Soprano

(Hanne) |

|

| Michael

Schade, Tenor (Lukas) |

|

| Florian

Boesch, Bass (Simon) |

|

|

|

| Konzertvereinigung

Wiener Staatsopernchor / Ernst

Raffelsberger, Chorus Master |

|

| Stefan

Gottfried,

Hammerklavier |

|

| Wiener Philharmoniker |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Conductor |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Großes

Festspielhaus, Salisburgo (Austria) -

luglio 2013 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

| A

co-production of ORF, ZDF for 3sat and

UNITEL |

Edizione DVD

|

| Euro

Arts Music - 2072678 - (1 dvd) - 150'

00" + 25' 00" - (c) 2014 | Unitel (c)

2013 - (DE) GB-DE-FR |

|

|

Notes

|

"Here, It's Just

Simon Speaking..."

When

Joseph Haydn completed his fourth and

final oratorio at the beginning of

1801 the 69-year-old composer was

famous throughout Europe. Born in 1732

as the son of a humble wheelwright,

Haydn grew up in a rural, peasant

environment. That such a child should

make his way eventually to the

position of court composer was an

extremely rare occurrence. Even in his

days at royal courts, however, Haydn

still felt a close and intimate

attachment to Nature and to life in

the countryside. When Baron Gottfried

van Swieten, then, presented to Hadyn

a libretto on the theme of The

Seasons, he found in the old

composer a worthy partner in his own

veneration for Nature. Besides being a

prominent patron of late-18th- Century

composers and musicians -

earning himself the nickname of

"the Patriarch of l\/lusic" - van

Swieten was also a gifted and admired

connoisseur ofthe European literature

of his age. Born in Holland, he

developed, in the course of his career

as a diplomat, an enthusiasm not only

for North German literature but also,

and quite especially, for the

literature of England. John Milton’s

Paradise Lost signified for the

Baron, as indeed it did for many poets

in England and in Germany as well, a

milestone which established a whole

new genre of poetic writing. The form

of religious-didactic

poetry practiced by Milton was an art

placed in the service of a pious

vision of God and the world which

deeply revered both the sublime and

the idyllic aspects of created Nature.

Another contemporary inspiration to

Van Swieten in this regard was the

British poet Henry Home, who also

wrote, besides about the dignity and

grace of Man, also about

the sublimity and grace of Nature,

seeing the moment of God's "Let there

be light!" as the

holiest of all moments and the

highpoint of the process of Creation.

A third kindred spirit here was the

Scottish poet James Thomson. Thomson's

poem cycle The Seasons was

extremely popular in the

German-speaking world in the second

half of the 18th

Century and it was this cycle of poems

that was eventually to form the basis

of the libretto of Haydn's Seasons.

Van Swieten, indeed, not only took

over the basic structure of Thomson's

poem-cycle but also

borrowed certain formulations almost

word-for-word. In other passages,

however, he embellished, lending much

greater emphasis than Thomson

originally had to various images of

Nature and idyllic scenes. This

tendencyto hyperbole on van Swieten's

part was one of the few causes of

disharmony between librettist and

composer. Haydn - who had, in contrast

to the city-raised nobleman, an

unromantic conception of Nature based

on long direct experience - described

certain passages that van Swieten

offered him as "Frenchified tosh". The

positive veneration of Nature in which

the highly-cultured van Swieten took

delight seemed, at times, to be more

affectation than poetry to the court

composer raised among struggling

peasants. For all that, though, van

Swieten's and Haydn's collaboration

was mostly harmonious and mutually

enriching. Van Swieten even sometimes

added to the texts he passed on to

Haydn extensive and precise notes on

how he felt certain passages should be

set to music; even more astonishingly,

Hadyn accepted these suggestions - not

always, perhaps, but often and

gratefully. In its basic conception,

Haydn's Seasons can be considered as a

counterpartto The Creation,

the libretto for which was also

written by van Swieten. Whereas The

Creation describes how God made

the world and the first man, The

Seasons tells of how Man

lives in Nature, under the natural

laws that God imposed upon the world.

But according to the religious view

favoured by van Swieten - typical of a

deistic theology modified by the

influences of the 18th-Century

Enlightenment - Man can

only live in harmony with Nature if he

earns his right to natural existence

by hard work and virtuous conduct. In

this we see the specific form of piety

in the face of created Nature which is

peculiarly characteristic of the

libretto. Those natural cycles which

unfold to the rhythm of the seasons

can be been seen here also as

metaphors for the birth and mortality

of Man himself.

The Seasons, then, is very much a work

of the Enlightenment period in that

Man stands at its very centre. Earthly

human existence also comes very

concretely to expression within the

text through the description of

various individual castes within rural

society: "Simon, a tenant farmer",

"Luke, a young peasant", "some peasant

folk", or "hunters".

"In The Creation

the angels told stories of God, but in

The Seasons it's just Simon

speaking" (Haydn). This remark

expresses the most basic principle

which governed Haydn's setting to

music of van Swieten's text. Whereas

The Creation sets about trying to find

an adequate form of representation for

what is transcendent, heavenly, The

Seasons is the decidedly earthly

counterpart to the earlier "heavenly"

oratorio. In this

context the music Haydn wrote for this

later work was also of a markedly more

"secular" character. Both van

Swieten's textual accounts of Nature

and Haydn's redescriptions of these in

music emerge still, indeed, from a

certain context of spiritual faith and

understanding (that of the "deism"

typical of a certain Enlightenment and

favoured by van Swieten in

particular). But thanks to its

unfolding, through music, of the

day-to-day lived experience of the

farmer and the peasant the score of The

Seasons also comprises elements

that cling as close to hard material

reality as any product of a more

purely materialist vision of the world

might have done. It

was surely the desire to do full

justice to these highly concrete and

material elements of the libretto he

was working with that prompted Haydn

to make of the score of The

Seasons a prime example of

so-called "programme

music" and to apply without

reservation the technique which has

come to be known as "tone painting".

He attempts, for instance, to give

direct musical accounts of the

presence of various animals: the cry

of the quail or the chirping ofthe

grasshoppers. Already Van Swieten,

indeed, had urged Haydn in his notes

to include "sound effects" of the

greatest possible realism in the

passages evoking scenes of hunting or

herding. These suggestions of the

Baron's sometimes resulted in strange

formal and musical oddities. As for

example in the "storm scene" which

anticipates, in its rhythmic but

harmonic dynamism, the famous fourth

movement of Beethoven's Pastoral

Symphony. So as to lend extra

emphasis to different descriptions and

events, Haydn also made use of a

special type of formal musical

dynamics, fusing various partial

formstogetherto create larger

complexes. For example, in the joining

of recitative and final chorus to form

a single great scene in the aria See

here, o foolish Man. As he had

already done in The Creation,

Haydn draws much of his inspiration

also in The Seasons from the

musical style of Handel, who succeeded

in synthesizing sacred music with aria

and Lied structures drawn from

the secular realm. This is nowhere

clearer than in the so-called Spinning

Song from the Winter

part, and the fugue "in praise of

industry" (Oh toil! Oh honest

toil!) from the Autumn

part of the oratorio. These passages

are (very unusually for the oratorio

form) composed in a popular style with

comic and ironic undertones. The Spinning

Song is a piece of social

criticism once again very much in the

spirit of the 18th-Century

Enlightenment (the peasant girl fools

the nobleman) and this message is

comically emphasized by the music it

is set to. And the inherent irony of

the Honest toil! fugue is

pointed up clearly enough by Haydn's

alternative description of it as "the

drunken fugue" - a satirical intention

underscored, here too, by the music: a

deliberate muddle and confusion of

competing voices. Perhaps it was just

this close juxtaposition of

contrapuntal sophistication and Lied-like

simplicity - that is to say, Haydn's

synthesis of academic and "folk-music"

styles - that made it difficult for

contemporary audiences at the piece's

first performances to receive it with

the enthusiasm with which they had

received The Creation. And yet

in the end, not least because of the

librettist they share, it is hard to

consider the two works as separate and

independent of one another.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt is also of this

opinion: "There can be no question but

that these are complementary works

[...] Once he had composed The

Creation, Haydn had no choice

but to compose The Seasons."

Harnoncourt is not only a conductor

but also a passionate researcher into

the history of music. In

addition to his conducting and

playing, he has also been active as a

musicologist, publishing works on the

theory and philosophy of music. His

analyses still count today as standard

works in the field of historically

informed performance of classical

music. After studies at the Vienna

Music Academy he became a cellist with

the Vienna Symphony. In 1953 he

founded, together with his wife Alice,

the orchestra "Concentus Musicus

Wien", with whom he has, for many

years, been attempting to reproduce as

closely as possible, using original

instruments, the musical performance

practices of the Renaissance and

Baroque eras. Along with his numerous

concert appearances in Europe,

Nicolaus Harnoncourt has also made a

name for himself as an opera

conductor. In March 2012 he was also

nominated an officer of the French Legion

d'Honneur. His many appearances

have made him particularly well known

for his contribution to the revival of

the historically informed performance

of older music.

Christophe

Witte

Translation: Dr. Alexander

Reynolds

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|