|

|

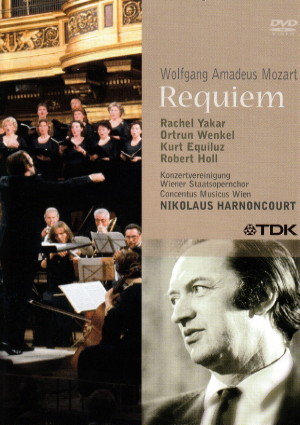

1 DVD

- 8 24121 00195 7 - (c) 2006

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Requiem d-moll, KV 626 |

|

|

| Ergänzungen von Xaver

Süßmayr - Neue Instrumentierung von

Franz Beyer |

|

|

|

|

|

| I. Introitus:

Requiem: Adagio |

4' 18" |

|

| II.

Kyrie: Allegro |

3'

03" |

|

| III. Sequenz: |

19' 13" |

|

| - Dies irae: Allegro

assai |

1' 54" |

|

| - Tuba mirum: Andante |

3' 34" |

|

| - Rex tremendae |

1' 51" |

|

| - Recordare |

5' 46" |

|

| - Confutatis: Andante |

2' 19" |

|

| - Lacrimosa |

3' 44" |

|

| IV.

Offertoriun: |

7'

30" |

|

- Domine Jesu

|

3' 52" |

|

| - Hostias |

3' 38" |

|

| V. Sanctus |

1' 49" |

|

| VI. Benedictus |

5' 27" |

|

| VII. Agnus Dei |

3' 17" |

|

| VIII. Communio: Lux

aeterna |

6'

53" |

|

BONUS

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750) |

|

|

| Cantata "Komm, du süße

Todesstunde", BWV 161 |

18' 53" |

|

| - Aria (Alto) "Komm, du

süße Todesstunde" |

4' 52" |

|

| - Recitativo (Tenore) "Welt,

deine Lust ist Last!" |

1' 45" |

|

| - Aria (Tenore) "Mein

Verlangen ist, den Heiland zu umfragen" |

5' 25" |

|

| - Recitativo (Alto) "Der

Schluß ist schon gemacht" |

2' 16" |

|

| - Chor "Wenn es meines

Gottes Wille" |

3' 13" |

|

| - Choral "Der Leib zwar

in der Erden" |

1' 22" |

|

|

|

|

| Rachel Yakar,

Sopran (Mozart) |

|

Ortrun Wenkel,

Alt (Mozart & Bach)

|

|

Kurt Equiluz,

Tenor (Mozart & Bach)

|

|

Robert Holl,

Baß (Mozart)

|

|

|

|

Konzertvereinigung

Wiener Staatsopernchor /

Gerhard Deckert, Choreninstudierung

|

|

| Concentus Musicus

Wien |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Grosses

Musikvereinssaal, Vienna (Austria) - 1

novembre 1981

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Franz

Kabelka

|

Edizione DVD

|

| TDK

- 8 24121 00195 7 - (1 dvd) - 55' 00" +

Bonus 21' 00" - (c) 2006 | ORF (c) 1982

|

|

|

Between Tradition and

Innovation

|

Performances of

Mozart's Requiem have always enjoyed a

very special status in Vienna. As we

know, Mozart was working on this

setting of the Mass for the Dead when

he died in 1791. Every year, at around

the time of his death, it is performed

in Vienna’s churches, including St

Stephen’s Cathedral, where his remains

were blessed on 6 December 1791 before

being taken to the cemetery at St

Marx's used by the parish of St

Stephen in which the composer had

died. There he vvas buried in a common

grave in keeping vvith the custom of

the time. But performances of the

Requiem are also given at other times

of the year in Vienna's many concert

halls. Traditionally, the version of

the work that is performed is the one

prepared by Mozart's pupil, Franz

Xaver Süßmayr, at the request of his

widow, Constanze, the missing parts

being added from sketches in a style

similar to that found in the sections

that had already been completed.

Süßmayr’s own contribution is limited

chiefly to the orchestration. In this

form, Mozart’s Requiem was one of the

most widely performed works of sacred

music even by the 19th century. In the

wake of the early-music revival, with

its desire to return to the original

form of pre-Classical and Classical

pieces, there have been attempts to

“correct” Süßmayr’s work and free

Mozart’s Requiem from the

sentimentality with which it became

associated in the 19th century, an age

that privileged Romantic textures and

sonorities.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt was one of the

first conductors and musicologists to

set this development in motion.

Harnoncourt was born in Berlin in 1929

but is an Austrian citizen. He was

still a rank-and-file cellist with the

Vienna Symphony Orchestra when, in

1953, he and his wife, the violinist

Alice Harnoncourt, joined forces with

some of his colleagues to found the

Concentus Musicus. They played on

period instruments, initially

performing Renaissance and Baroque

works. It was in no small part thanks

to their many award-winning recordings

that attitudes to the pre-Classical

repertory changed, changes that

affected not only the way in which

these works were interpreted but also

the listening habits and expectations

of audiences as a result, not least,

of the fact that many musicians and

ensembles followed their example. As a

conductor, above all, Harnoncourt

himself soon moved on to the works of

Viennese Classicism, whose original

sounds he sought to recreate. After

his highly successful cycle of

Monteverdi operas in Zurich, he began

a Mozart cycle at the same opera

house. Starting with Idomeneo

in 1980, he went on to add Mozart's

other main operas, presenting them in

a style that differed substantially

from what was usual at that time.

Today Harnoncourt is regarded as one

of the leading conductors of his age,

at home in a repertory that embraces

not only the great symphonies of

Brahms, Dvořák and Bruckner and the

operas of Haydn, Mozart and Schubert

but also such popular favourites as Aida,

Carmen and even Die

Fledermaus. But he was still at

the start of this development in the

autumn of 1981, when the present

recording was made. It says much for

the initiative of the Vienna State

Opera Chorus (officially known in its

concert manifestation as the

Konzertvereinigung Wiener

Staatsopernchor) that for their first

All Saints' Day concert they did not

choose one of the conductors familiar

to them from the State Opera but

preferred to work with Harnoncourt, a

sure sign that they were willing to

strike out in a new direction here.

The importance of the occasion was

also recognized by Austrian radio and

German television, both of which

recorded and broadcast the

performance.

By 1981, concerts of the Vienna State

Opera Chorus could already look back

on a long tradition. As long ago as

1927 its members had decided to follow

the example of their orchestral

colleagues, who in 1842 had

established a democratically

structured artists' collective under

the title of the “Vienna

Philharmonic". And so they founded

their own independent organization,

the "Konzertvereinigung Wiener

Staatsopernchor", which has never been

merely a concert choir. Independent

events, tours, guest appearances at

the Salzburg Festival and elsewhere

and, last but not least, its countless

recordings have all confirmed the

status and reputation of this

professional body of singers.

The present recording is taken from

the ORF archives and conveys an idea

of the very special atmosphere in the

Goldener Saal of the Vienna

Musikverein, a scene familiar to

millions of television viewers from

the Vienna Philharmonic’s annual New

Year Concerts. And yet, although the

present concert also took place during

the late morning, the occasion could

hardly have been more different in

terms of its seriousness of purpose

and concentration on music that is

devoted not to pleasure but to

thoughts of death and eternity.

Equally unusual is the combination of

the Vienna State Opera Chorus and the

reduced forces of the Concentus

Musicus playing on period instruments.

For the present performance

Harnoncourt chose the edition of the

work prepared by the German musician

and musicologist Franz Beyer, a

version that was receiving its

Viennese premiüre. It is above all in

its instrumentation that Beyer's

version differs from Süßmayr’s, a

version which, in Beyer's view,

"translated Mozart's mighty fragment

into the milieu of the popular

language of the liturgical music that

was much cultivated at that time." On

the strength of a stylistic comparison

with other works from the final period

in Mozart’s life, Beyer came to the

conclusion that Mozart would have

orchestrated the work differently,

with more sparing textures and more

ascetic sonorities. This approach is

underscored by the Concentus Musicus’s

use of period instruments. Natural

trumpets, hand horns, an early

18th-century kettledrum and two

basset-horns not only blend in a novel

way with the woodwinds and strings,

they also influence the vocal aspect

of the work, while also affecting the

dynamics of the performance and even

the choice of tempos. Even after a

quarter of a century, the listener and

spectator can still be thrilled by the

attentiveness with which the soloists

and members of the Vienna State Opera

Chorus react to these different sounds

and to the often unfamiliar phrasing

of the Concentus Musicus, whose

players support the conductor’s

interpretation to the hilt.

Harnoncourt, it will be noted,

conducts without a baton.

The first part of the concert was

evidently designed to put listeners in

the right frame of mind for the day as

a whole and for Mozart’s Requiem in

particular: it comprised a performance

of Bach's Cantata 161, Komm, du

süße Todesstunde, in which two

solo singers (alto and tenor) and a

four-part choir are set against an

instrumental ensemble made up of

strings, organ and continuo, together

with two concertante recorders.

Harnoncourt’s vast experience in this

field - together with Gustav

Leonhardt, he recorded all Bach’s

sacred cantatas with the Concentus

Musicus and various chamber choirs -

is impressively documented here.

Gottfried

Kraus

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|