|

|

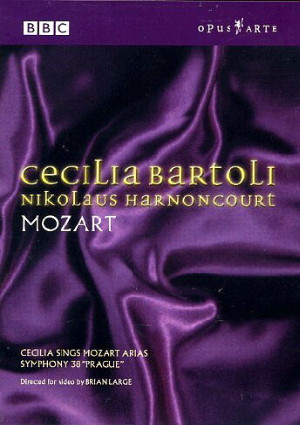

1 DVD

- OA 0869 D - (c) 2003

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Aria: "Voi avete un cor

fedele", KV 217 |

7' 45" |

|

| Aria: "Vado, ma dove? Oh

Dei!", KV 583 |

4' 48" |

|

| Aria: "Giunse alfin il

momento", KV 492 (Le Nozze di

figaro) - "Al desìo di chi

t'adora", KV 577 |

8' 43" |

|

| Aria: "Un moto di gioia",

KV 579 |

4' 42" |

|

| Aria: "Bella mia fiamma,

addio... Restam oh cara", KV 528 |

12' 52"

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 38 in D

major, KV 504 "Prague" |

37' 44" |

|

- Adagio. Allegro /

Adnate / Finale: Presto

|

|

|

|

|

|

BONUS: Filming Notes

|

12' 58" |

|

| BONUS: In Rehearsal |

16' 53" |

|

|

|

|

| Cecilia Bartoli,

soprano |

|

|

|

| Concentus Musicus

Wien |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Conductor |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal,

Graz (Austria) - 13-14 luglio 2001 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

| Abbey

Road Interactive Producer: Dan Ruttley

|

Edizione DVD

|

| Opus

Arte - OP 0869 D - (1 dvd) - 77' 00" +

Bonus 30' 00" - (c) 2003 |

|

|

Notes

|

MOZART'S JOURNEY

TO PRAGUE

Mozart's

concert arias form an area of his

output that has seldom received the

attention it deserves. In

some cases, it is true, the

comparative neglect of these pieces is

due to the music's sheer difficulty:

almost all of them were tailor-made to

exploit the vocal abilities of

specific singers,some of whom had

spectacularly wide-ranging and

flexible voices.Very few of the arias

were actually designed as independent

concert pieces: the majority were

composed as insertion-numbers (or

sometimes substitutions for original

arias) for revivals

of operas either by Mozart himself, or

by other composers.This was common

practice at the time, and the

intention was to afford one or more

members of the new cast additional

opportunities to display their talent

- or, in the case of substitution

arias, to provide a singer with a new

number more specifically suited to his

or her dramatic skills.

Mozart composed the aria Voi avete

un cor fedele in the autumn of 1775,

for insertion into Galuppi's comic

opera Le nozze di Dorina [to a

libretto by Carlo Goldoni],

which was being performed in Salzburg

by a visiting Italian opera troupe.

Mozart's aria shows him already at the

age of 19 a master of

musical irony. It

alternates slower passages in which

Dorina gently mocks the ease with

which her suitor can be faithful as

long as he remains her lover; and

quick sections where she expresses her

thoughts about what he would get up to

if they were to become engaged.

Considerably later is Vado, ma

dove? Oh Dei! K.583 - one

of two new arias Mozart provided for

the revival of the comic opera Il burbero di

buon core by the Spanish

composer Martin y Soler in Vienna's

Burgtheater, on 9 November 1789.

Martin's popularity was such that

Leporello is able instantly to

recognise a tune from another opera

buffa of his, Una Cosa rara,

when it is played by the wind-band in

the supper scene of Don Giovanni.

It was probably no

coincidence, either, that the

librettist of both Il burbeto di

buon core and Una cosa rara

was Lorenzo da Ponte, who is likely

also to have supplied the words for

Mozart's new insertion arias. They

were written for the Italian soprano

Luisa Villeneuve, who was to take the

role of Dorabella in the premiere of Così

fan tutte two months later.

The principal characters in Il burbero di

buon core are Giocondo and his

wife Lucilla.Giocondo's business

ventures are going badly, and his

creditors will no longer wait for

repayment. Having initially forbidden

Lucilla to meddle in his family

affairs, Giocondo is now forced to

explain the situation to her. In the

first part of her aria Vado, ma

dove? Lucilla, believing herself

to blame for their predicament,

wonders whether it would be better for

her to leave; but in the slower second

section, with its prominent parts for

the clarinets Mozart was to use with

such warmth in Così fan tutte,

she seeks guidance from love.

The rondo Al desio di chi t’adora

K.577 and the much more light-hearted

Un moto di gioia mi sento K.579

were substitution arias Mozart

composed for the famous soprano

Adriana Ferrarese del Bene [or 'La

Ferrarese', as he called her) when she

took the role of Susanna in the highly

successful Viennese revival of Le

nozze di Figaro which opened on

29 August 1789. Al

desio replaced Deh vieni non

tardar from Act Four, in which

Susanna taunts the eavesdropping

Figaro by feigning to anticipate the

pleasures of a secret assignation.The

new aria was as different from the

original as could be imagined: while Deh

vieni is a lilting serenade with

pizzicato strings accompanying the

bright tones of a wind trio consisting

of flute, oboe and bassoon, the much

more sensuous Al desio is

darkly scored for muted strings with a

pair each of horns, bassoons and

basset-horns (low-pitched members of

the clarinet family). Following its

opening bars the long slow opening

section has the voice accompanied for

the most part by the wind instruments

alone, with the intermittent addition

of no more than single-line support

from the cellos and basses. As Susanna

looks forward to her amorous

encounter, Mozart unfurls a series of

arabesques on the first bassoon and

first basset-horn (the latter

accompanied by his colleague playing

in the contrasting bottom register of

the instrument, several octaves

below), and the section ends with an

elaborate vocal cadenza on the word

'sperar' ('hope'),

accompanied by all six wind players.

Towards the end of the cadenza the

violins enter with a single pizzicato

line, as though Mozart had suddenly

remembered the serenade context of the

original aria, and Susanna were urging

on the pleasures of love by plucking

at the strings of some invisible

guitar. At the point where she

confesses she can no longer contain

her desire, the erotic tension is

dispelled by the sudden start of the

Allegro. It is, surely,

only the fame of Deh vieni

that has prevented this remarkable

aria from being better known. It is

sting on the present DVD together with

the recitative, Giunse alfin il

momento, which precedes Deh

vieni in the familiar version of

the opera.

Much more straightforward than Al

desio is the arietta Un moto

di gioia, designed

to be sung in place of Susanna's

second-Act aria Venite,

inginocchiateve, as she

disguises Cherubino en travesti

and instructs him on how to appear

more feminine. Its

simple tune is in more popular style

than the aria it replaces, and its

waltz-like rhythm is given an

irresistibleViennese lilt in the

present performance by Cecilia Bartoli

and Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Mozart

himself was confident the new aria

would be a success.”The Little Arietta

for the Ferraresi", he told his wife,

Constanze,"should go down well,

provided she takes the trouble to

perform it unaffectedly, which I

very much doubt." Mozart’s

reservations about the soprano's

dramatic talents did not, however,

prevent him from allowing her to take

the part of Fiordiligi in the premiere

of Così fan tutte; but in 1791

a scandal involving her and her lover

Da Ponte led the Emperor to dismiss

her from the Court Opera

troupe. It is quite

widely believed that ‘La Ferrarese’

was the sister of Louisa

Villeneuve, the first Dorabella. If

that is so, then the description in Così

of the two principal female

protagonists as being sisters from

Ferrara acquires added resonance.

(There had been no shortage in Da Ponte's

libretto for Don Giovanni of

in-jokes of this kind pertaining to

members of the cast and orchestra.)

Bella mia fiamma,

addio K.528 was composed for the

Bohemian soprano Josepha

Duschek (or Dušek).

Legend has it that she locked the

composer in a room until he had

completed a new aria for her, and

that, for his part, Mozart agreed to

hand it over only on condition that

she could perform it a prima vista

- a task he deliberately made as

difficult as possible. The anecdote

was related many years after the event

by Mozart's son Carl Thomas, and the

music seems to confirm its basis in

fact: the phrase in the aria's slower

opening section significantly setting

the words ’Quest'affano, questo passo

è terribile per me' is

sung to a long and tortuously

chromatic phrase which must indeed

have been difficult to sight-read.

Moreover, the phrase occurs three

times, and on each occasion the layout

of the melodic line is subtly altered

in such a way that the voice has to

leap upwards, or take a plunge

downwards to the lower octave, at a

different point. The words themselves

have a double meaning: either, in

their original dramatic context. 'This

anxiety, this step is cruel for me';

or, as they may have confronted Josepha

Duschek, 'This lack of breath, this

passage terrifies me'. Mozart clearly

enjoyed himself at the singer's

expense, though the phrase in question

is in fact deeply serious in tone -

indeed, despite the circumstances in

which it arose, this is one of the

greatest and most profound of all

Mozart's concert arias.

Mozart and Duschek were actually old

friends: Josepha and her

husband, the Bohemian composer Franz

Xaver Duschek (not to

be confused with his more famous

younger compatriot Jan

Ladislav Dussek), had visited the

Mozart family in Salzburg in the

summer of 1777. On

that occasion Mozart had composed his

scena Ah, lo previdi K.272 for

Josepha. Now, exactly

a decade later, Mozart and his wife

were house-guests of the

Duscheks at their summer villa on the

outskirts of Prague. Mozart had

travelled to Prague in preparation for

the premiere there of Don Giovanni,and

he put the finishing touches to the

score in the garden of the villa. The

recitative and aria Bella mia

fiamma - resta, oh cara was

composed on 3 November 1787, less than

a week after the opera's triumphant

first night.

The text of the scena comes from a

mythological festa teatrale by the

Neapolitan composer Niccolò

]omelli called Cerere placata

('Ceres appeased'). The aria is sung

by Titano, King of Iberia. (The role

is a castrato one.) He has asked

Ceres, Queen of Sicily, for the hand

of her daughter Proserpina. When his

request is rejected he abducts

Proserpina and Ceres vows vengeance

for his action. By conjuring

up a storm which drives his ship onto

the shores of Sicily, she manages to

take Titano prisoner; but instead of

condemning him to death, she decides

to banish him forever. Bella mia

fiamma is Titano’s tender

farewell to Proserpina, though it is

addressed at the same time to Ceres,

and to his friend Alpheus.

As was his custom, Mozart sets the

opening recitative for voice and

strings only; and the fact that the

initial bars of the aria are scored in

the same way enhances the surprise of

the entrance of oboe and bassoon, with

an interpolated phrase, in the aria's

fifth bar. Following this, the music

takes a sudden plunge into the minor,

for the words 'acerba morte' ('bitter

death'), though the dark tinge is

short-lived. Much more prolonged and

languorous in effect is the yearningly

chromatic passage in which Titano bids

farewell ('addio per

sempre'), and which culminates in Josepha

Duschek’s sight-reading

test. In the final

section of the aria, Titano's despair

finds expression in an urgent Allegro.

Mozart and Josepha

Duschek performed Bella mia fiamma

at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in May 1789,

at a concert in which Mozart also

played his piano concertos K.456

and 503. Duschek included it again at

the Gewandhaus in October 1796,

five years after Mozart's death, when

she also sang arias from Idomeneo

and La Clemenza di Tito.

Already by 18l5 the

stature of Bella mia fiamma as

"Mozart's truly great scene and aria"

was acknowledged in a report in the

influential Leipzig Allgemeine

musikalische Zeitung.

The occasion on which he composed Bella

mia fiamma

was by no means Mozart's first visit

to Prague. He and Constanze had

travelled there in the early months of

the same year of 1787 for the

production of Le Nozze di Figaro

at the National Theatre. The opera had

already been popular in Vienna,

despite political intrigues that had

conspired to dampen its success; but

in Prague, where Mozart's music always

met with great acclaim, the effect it

produced was nothing short of

sensational. It was

this production alone that saved the

fortunes of the impresario Pasquale

Bondini, who had been on the verge of

bankruptcy.

The Mozarts had arrived in the

Bohemian capital on 11 January,

and that same evening they were

invited to one of the weekly balls

given at the house of Baron Bretfeld.

Mozart told his friend the singer

Gottfried von Jacquin

that all the beauties of Prague

gathered there:

That would have

been something for you, my friend!

I mean, I

can see you - running do you

think? - no, limping after all the

beautiful girls and women. I did

not dance or eat - the former,

because I was too tired; the

latter, out of my in-bred

stupidity. But I watched

with great pleasure how these

people pranced around with such

enjoyment to music from my

'Figaro' transformed into

contredanses and German dances.

For here, nothing is talked about

except - Figaro; nothing is

played, blown, sung and whistled

except- Figaro; no opera visited

except - Figaro, and forever

Figaro, It’s

certainly a great

honour for me.

The

success of Figaro was such

that Bondini was able to commission a

new opera from Mozart for the

following season.That new work was Don

Giovanni. Meanwhile, during his

first stay in the Bohemian capital,

Mozart had given a piano recital on 19

January, and had also

directed the new symphony he composed

in preparation for his visit. The

effect the Prague Symphony had

on the audience of the day is

described by Mozart's friend and early

biographer Franz Xaver Niemetschek,

who, following the composer's death,

was entrusted with the education of

his son Carl. Writing ten years after

the event, Niemetschek misremembered

Mozart as having written more than one

new work, but there is no reason to

doubt the accuracy of the remainder of

his testimony. "The symphonies

[Mozart] composed for this occasion

are true masterpieces of instrumental

composition, full of surprising

transitions, and have a quick, fiery

tempo, so that they immediately raise

the soul to expect something sublime.

This applies particularly to the grand

symphony in D major,

which is still a favourite with the

Prague public, although it has

probably been heard a hundred times."

In the Salzburg of

Mozart's youth the three-movement

symphony had been almost the norm,

rather than the exception.Its

form, which found no place for the

sectionalised minuet movement, is one

that evolved out of the Italian opera

overture - itself a continuous piece,

but one which generally fell into a

quick-slow-quick pattern, with the

last section often being a more or

less literal reprise of the first.

Even in Mozart's output, the

distinction between symphony and

overture is one that is not always

easily made. Mozart himself adapted

several of his earlier overtures as

symphonies, more often than not by

providing them with a new finale; and

there were occasions when he carried

out the reverse process: the overture

to La finta semplice, for

instance, was a reworking of a

pre-existing symphony, and in its

revised version the overture, in its

turn, circulated widely as a purely

symphonic work.

Mozart's interest in this hybrid

symphonic form lasted until as late as

1779, when he wrote

his single-movement Symphony in G

major K.318. But he

continued to cultivate a symphonic

form in three discrete movements

intermittently throughout his career.

The Prague Symphony K.504 is

the last and the greatest of his works

in this form. In the

German-speaking world

the Prague is known as the

symphony ‘without a minuet'; and

certainly, as a profound symphonic

masterpiece in three movements it

occupies a unique

position in the Classical repertoire.

If the Prague

Symphony was composed between Le

nozze di Figaro and Don

Giovanni, it is a work that

shares some of the dramatic character

of both operas. Its

effervescent finale

seems to echo the hurried duet from

the second act of Figaro, as

Cherubino,watched by the horrified

Susanna, jumps out of the upstairs

window; while its imposing slow

introduction, with its early turn to

the minor, anticipates the much darker

world of Don Giovanni. Perhaps

it is not by chance that all three

works share the same basic tonality of

D, major or minor.

The Prague is not the first of

Mozart's mature symphonies to begin

with a slow introduction - that

distinction belongs to the Linz

K.425 - but its opening

Adagio is unique in its dark, brooding

atmosphere. With the exception of the

first fifteen bars, the entire

introduction is set in the minor, with

trumpets and drums adding weight and

solemnity to the proceedings. (With

his timpani forcibly restricted to

only two pitches, Mozart maintains

their use through an intricate series

of modulations with remarkable

resourcefulness.) The Allegro that

follows is an object-lesson in how to

create a large, imposing movement out

of the slenderest of musical

materials. Almost everything in the

piece arises out of its concise main

subiect, with the violins' throbbing,

syncopated note accelerating into an

important repeated-note rhythmic figure,

while the lower strings unfold a

smooth, sinuous idea in long notes,

and the wind instruments finally

contribute a toy fanfare which -

together with the repeated-note figure

- will later form the

basis of the movement's central

development section. (The little

fanfare itself is strikingly

reminiscent of Figaro's famous 'Non più

andrai'.) Unusually for Mozart, the

second stage of the exposition uses

the same material, but there is also a

meltingly beautiful new theme which,

with sublime simplicity, takes

its point of departure from the

tiny phrase on the violins by which it

is approached.

The use of a seemingly insignificant

idea in order to generate new material

continues in the slow movement, whose

opening theme is followed by an

afterthought, quietly given out in

octaves by the strings, which will

assume considerable importance in the

further course of events. This,

indeed, is a piece in which every

phrase seems to grow with unerring

logic out of the last. As for the

helter-skelter finale, it finds Mozart

throwing ideas back and forth between

the sections of the orchestra, in a

manner which shows how much confidence

he must have had in the virtuosity of

the wind players he had at his

disposal. The development section has

the principal subiect's quietly

syncopated melodic line striding

through the entire orchestra, to

tremendous effect - indeed, so

breathlessly agitated is the music

here that Mozart does not relax its

forward momentum even at the start of

the recapitulation. Instead,

development and recapitulation are

fused to a startling degree, with the

main subject severely

condensed, and the development's

violent outbursts continuing until the

arrival ofthe second subject.

All in all, it is small

wonder Mozart's faithful Prague

public was so electrified by

the music he composed for it.

Misha Donat

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|