|

|

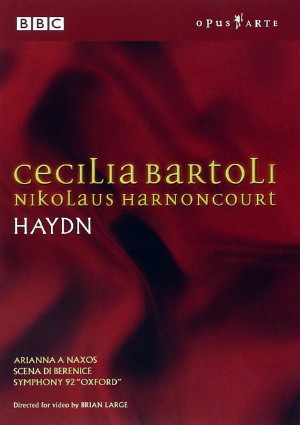

1 DVD

- OA 0821 D - (c) 2003

|

|

| Franz Joseph Haydn

(1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 92 in G

major "Oxford", Hob. I/92 |

25' 32" |

|

| - Adagio.

Allegro spiritoso / Adagio / Menuet

& trio, allegretto / Presto |

|

|

|

|

|

| Cantata "Arianna a Naxos,

Hob. XXVIb:2 |

22' 21" |

|

|

|

|

| Cantata "Scena di

Berenice", Hob XXIVa:10 |

14' 47" |

|

|

|

|

BONUS: In Rehearsal

|

14' 27" |

|

| BONUS: Styriarte:

Portrait of a Festival |

6' 26" |

|

|

|

|

| Cecilia Bartoli,

soprano |

|

|

|

| Concentus Musicus

Wien |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Conductor |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal,

Graz (Austria) - 13-14 luglio 2001 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

| Abbey

Road Interactive Producer: Dan Ruttley

|

Edizione DVD

|

| Opus

Arte - OP 0821 D - (1 dvd) - 62' 00" +

Bonus 21' 00" - (c) 2003 |

|

|

Notes

|

HAYDN IN LONDON

AND OXFORD

Early

in December 1790 the impresario ]ohann

Peter Salomon walked into Haydn's

rooms inVienna and introduced himself

with the now famous words, "I am

Salomon of London and have come to

fetch you. Tomorrow we will arrange an

accord." He had made several

previous attempts to lure the great

composer to England, but as he well

knew the moment was now opportune:

Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, Haydn's

employer for nearly 30 years, had died

iust three months earlier, and one of

the first acts of his successor,

Prince Paul Anton II, was to disband

the musicians of the Esterháza court.

Although Haydn was retained on a

pension, his position as Kapellmeister

became a purely honorary one and he

was free to accept employment

elsewhere.

After a rough Channel crossing Haydn

beheld the white cliffs of Dover for

the first time on New Year's Day,

1791. He was in his late fifties at

the time,and his European fame

surpassed even that of Mozart. His

appearance in London was greeted with

immense excitement. A few days after

reaching the capital he wrote to his

old Viennese friend Maria Anna von

Genzinger:

My arrival caused

a great sensation throughout the

whole city, and I was taken around

all the newspapers for three days.

Everyone is eager to know me. I

have already had to dine out six

times, and if I wanted I could be

invited every day; but first I

must consider my health, and 2nd

my work... Yesterday I was invited

to a grand amateur concert, but I

arrived a little late, and when I

showed my ticket they wouldn't let

me in but led me to an antechamben

where I had to wait until the

piece which was then being played

in the hall was over. Then they

opened the doon and I was

conducted, on the arm ofthe

entrepreneur up the centre of the

hall to the front of the

orchestra, amid general applause,

and there I was stared at and

greeted by a great number of

English compliments. They assured

me that such an honour had not

been conferred on anyone for 50

years.

Haydn

gave his first concert at the Hanover

Square Rooms on 11 March 1791. We

cannot be sure as to which of his

symphonies he performed on that

occasion, but it is likely to have

been No. 92 - the one known as the

"Oxford". It was not a new work

(though it was new to England) and

Haydn had actually composed it not for

London, but for Paris. In 1784 he had

been approached by a Masonic concert

society called Le Concert de la

Loge olympique, with a

commission to write a set of six new

symphonies. The chief instigator of

the commission was one of the

society's backers,

Claude-François-Marie Rigoley, Comte

d'Ogny. Haydn completed two of the

symphonies, Nos.83 and 87, and

possibly a third (No.85), in 1785; and

the remaining three - Nos. 82, 84 and

86 - the following year. The success

of these 'Paris' symphonies was such

that the Comte d'Ogny was able to

commission a further three symphonies

from Haydn some two years later. These

were Nos. 90-92, and it was the last

in this group that Haydn chose to have

performed when he was presented with

his honorary doctorate at the

University of Oxford, on 8 July 1791 -

hence the nickname by which it has

been known ever since.

According to Albert Christian

Dies,whose early Haydn biography was

based on conversations with the

composer, it was the famous music

historian Charles Burney who was the

motivating force behind Haydn's

degree:

He talked Haydn

into taking this step, and

travelled with him to Oxford. At

the ceremony in the University

Hall a speech encouraged the

assembled company to honour the

merits of a man who had risen so

high in the service of music by

presenting him with the doctor's

hat. The whole company was loud in

Haydn's praise, whereupon Haydn

was dressed in a white silk gown

with sleeves of red silk, a small

black hat of black silk was placed

on his head, and thus clothed he

had to sit on a doctor’s chair.

After this ceremony came music, in

which our [Gertrud] Mara, who was

in England at the time, sang.

Haydn was asked to perform

something of his own composition.

He climbed up to the organ loft,

turned to face the assembled

company whose eyes were all

directed towards him, grasped his

doctor's robe with both hands,

opened it, closed it again and

said as loudly and clearly as he

could: "I thank you." The company

well understood this unexpected

gesture; they appreciated Haydn 's

thanks and answered: "You speak

very good english."

"I

felt very comical in this gown"

[Haydn told me]; "and the worst

thing was that for three whole

days I had to go around the

streets dressed up like this. All

the same, I owe much to this

doctor’s degree in England -

indeed, I could say I owe it

everything. Thanks to it I got to

know the most important men and

gained entrance to the greatest

houses."

Haydn's

choice of symphony to have performed

on this occasion was a happy one: it

is one of his most sparkling and witty

works of its kind,and one that wears

its considerable learning lightly. It

is scored for a large orchestra,using

its trumpets and drums even in the

slow movemnent, where their sudden

eruption in the D minor middle section

lends the music weight and drama. This

imposing moment, which contrasts so

strongly with the gentle lyricism

ofthe remainder of the piece, seems to

offer a foretaste of the D minor

turbulence Haydn invoked so memorably

in his Nelson Mass nearly a

decade later. The Adagio also

contains, both in its middle section

and in its closing pages, striking

passages scored for the wind

instruments alone.

Altogether, Haydn's ear for orchestral

colour in this work is remarkable. The

trio of the minuet has hunting-calls

with strong off-beat accents for horns

and bassoons, accompanied by pizzicato

strings and punctuated by smooth

ascending and descending scales on the

arco violins. When the horn-calls

return during the trio's closing bars,

they are made to, overlap with the

scale figures, before both ideas

invade the entire orchestra. As for

the minuet itself, its second half

sets off with a dramatic plunge into

the minor, followed by an abrupt

moment of silence - as though the

music has been stopped dead in its

tracks. The effect is the more

striking when the piece is taken at a

relatively swift tempo, as in the

performance recorded here.

There are more stops and starts in the

opening bars of the finale's

powerfully canonic central development

section,where the movement's bubbling

main theme is transformed into

something altogether darker and more

dramatic. As presented at the outset,

the theme is given out in a skeletal

form by the first violins, accompanied

by nothing more than a ‘rocking'

octave on the cellos. The theme's

restatement passes to the flute an

octave higher, with the rapid

'tick-tock' accompaniment transferred

to an agile horn player; and the same

motion, this time a little more fully

scored, also features in the

altogether skittish second subject.

(When the second subject resurfaces in

the recapitulation the horn player

once more finds himself called upon to

join in the playful accompaniment.)

The variety of Haydn's orchestral

palette is manifested right at the

symphony's outset, where the main bulk

of the slow introduction is scored for

strings alone, with the eventual entry

of the wind instruments coinciding

with a darkening of the music's mood.

The introduction's closing bars are

left un resolved,and the quiet main

theme of the Allegro begins as though

in mid-stream - a feature Haydn

maintains each time the theme returns

during the course of the movement. But

perhaps the most striking aspect of

the Allegro is the manner in which the

music's intensity and instability are

continued in the recapitulation, in

such a manner that the music appears

to progress in a single uninterrupted

sweep from the start of the

development section right until the

end ofthe coda.

The cantata Arianna a Naxos

was probably composed in 1789, but it

achieved its greatest success in

Haydn's London concert season two

years later. It was the composer's own

favourite among his works of its kind

(though his judgement was made before

he had written the Scena di

Berenice) and the first of its

two arias was later much admired by

Rossini.

On 18 February 1791 Haydn played the

piano part of Arianna a Naxos

for a performance of the work with the

famous castrato Gasparo Pacchiarotti

at one of the "Ladies’ Concerts" given

in the Portland Place rooms of the

prominent London music patron Mrs

Blair. The occasion prompted the Morning

Chronicle to report:

The musical world

is at this moment enraptured with

a Composition which Haydn has

brought forth, and which has

produced effects bordering on all

that Poets used to sing of the

ancient lyre. Nothing is tallied

of - nothing sought after but

Haydn’s Cantata - or, as it is

called in the Italian School - his

Scena... It abounds with such a

variety of dramatic modulations -

and is so exquisitely captivating

in its larmoyant passages, that it

touched and dissolved the

audience. They speak of it with

rapturous recollection, and

Haydn's Cantata will accordingly

be the musical desideratum for the

winter.

Such

was the cantata's success that it was

repeated at a concert held in the

Pantheon (the opera house supported by

King George III) the following week.

This time the Morning Chronicle

was moved to comment: "The modulation

is so deep and scientific, so varied

and agitating - that the company was

thrown into extasies. Every fibre was

touched by the captivating energies of

the passion..."

The story of Ariadne, abandoned by

Theseus on the island of Naxos, and

despairing to the point of madness

before being comforted by Dionysus (or

Bacchus), whom she subsequently

marries, is one that inspired

composers from Monteverdi to Strauss.

Monteverdi's Lamento d'Arianna,

the sole surviving portion of his

opera on the same subject, was one of

his most celebrated compositions for

its power to stir the emotions.

Haydn sets his anonymous text in the

form of two extended recitatives, each

followed by a slow aria. The opening

instrumental passage portrays

Ariadne's awakening from sleep, while

the first of the two arias is perhaps

the closest Haydn ever came to a

Mozartian operatic style (notice, for

instance, the halting phrases that set

the words 'né resisto al mio dolor').

The aria ends with an anticipation of

the echo effect which in the following

recitative depicts the only reply

Ariadne receives to the words she

addresses to Theseus.

The second recitative contains a

remarkable series of chromatically

ascending chords, as Ariadne climbs a

rock in order to search the horizon

for a sign of Theseus. Her

deliriousness at the realisation that

he has abandoned her is accompanied by

a striking change of key, as the music

seems momentarily to lose all sense of

direction. Also graphically depicted

are the wind and the waves that carry

Theseus away from her forever, and -in

a sustained passage of syncopation -

the faltering of her steps as she

almost loses consciousness.

As for the final aria, it concludes

with a 'presto' in a dark F minor - a

key which frequently finds Haydn in

his most dramatic and agitated vein.

The closing bars - an intense

chromatic ascent followed by a

peremptory cadence - have a

smouldering intensity that is rare in

Haydn's music of the period, and the

wholly unexpected turn from minor to

major for the very last chord seems

only to underline Ariadne's manic

despair.

Haydn wrote his cantata for voice and

piano.He may well have intended to

orchestrate it himself, though he

never actually did so, and the version

we hear on the present DVD, which has

the singer strings, is one of

several arrangements of the piece made

during the early years of the

nineteenth century.

Haydn's final concert season in London

took place between February and May

1795. On 4 May at the King's Theatre

in the Haymarket he presented a

programme that included the premiere

of his last symphony, No.104 (knonn as

the "London") as well as a new

dramatic orchestral scena composed for

the famous Brigida Giorgi Banti, the

King's Theatre's principal resident

soprano. Banti had arrived in England

the previous year, and opinions as to

her musical talents differed widely.

The General Evening Post

reviewed her London debut in April

1795 in glowing terms:

The musical world

were gratifed on Saturday evening

by the first appearance of the

BANTI, and it is but justice to

say, that her performance was

worthy of her fame. Her first

bravura song generally electrified

the audience; in the succeeding

efforts she shewed that her powers

in the Cantabile are equally

transcendent. To these, she adds a

degree of intelligence and

attention to the business of the

scene, which interested every

careful Auditor in her success.

A

handbill for Haydn's concert of 4 May

has survived with marginal annotations

written by a member of the audience on

that historic occasion. The new scena

elicited the comment: "Banti has a

clear, sweet, equable voice, her low

& high notes equally good. Her

recitative admirably expressive. Her

voice rather wants fullness of tone;

her shake is weak and imperfect".

Banti's thin tone was rather more

vividly described by Haydn himself. In

his notebook he remarked, in his own

brand of pidgin-English, "She song

very scanty". Despite any such musical

shortcomings, however, the composer

was well satisfied with the financial

side of the evening's work: "The whole

company was thoroughly pleased, and so

was I. I made four thousand Gulden on

this evening. Such a thing is only

possible in England."

The Scena di Berenice was one

of Haydn's very few works which

Beethoven took as a direct model: his

concert aria Ah! Perfido of

1796 is patently influenced by it; and

it is interesting to note that Haydn's

scena was one of the works

included in a concert given in Vienna

on 22 September 1803, when the singer

was Anna Milder - Beethoven's first

Leonore. For this concert at the

Augarten, Haydn made some minor

adjustments to his score, the most

significant of which was to omit the

quiet opening bars featuring the wind

instruments. It has been suggested

that the composer was concerned lest

his subdued beginning be lost in the

chatter of the Viennese audience,

though he may have felt it better in

any case to start the work in

media res, with the impetuous

string passage that immediately

establishes Berenice's agitated frame

of mind. Be that as it may, the

present performance restores the

original version.

The text of the scena is taken

from Metastasio's Antigono.

Its subject and musical treatment are

remarkably similar to those of Arianna

a Naxos,and once again Haydn

provides a concluding aria in a dark F

minor. Just as the abandoned Ariadne's

despair turns to madness, so Berenice

struggles to come to terms with her

lonely fate following the fatal

wounding of her lover, Demetrio. She

begs him not to cross the river Lethe

without her, and implores God to

increase her suffering so that death

will claim her.

Berenice’s train of thought in the

opening recitative is vividly conveyed

by the music: a staccato string

passage to illustrate her vacillating

steps, tremolos for the icy shiver

that passes through her veins, an

excursion into the murky depths of C

flat major as the day darkens around

her; but above all, Berenice's

confusion is paralleled by the

wide-ranging tonal plan of the piece

as a whole.The initial recitative

passes through a C major arioso ('Aspetta,

anima bella'), before we

eventually reach a radiant E maior for

a short and remarkably beautiful aria

in Handelian style, 'Non partin

bel idol mio', whose dream-like

quality is heightened not only by the

remoteness of its key, but also by the

fact that it appears as a single

moment of serene calm between the

dramatic opening recitative and the

scorchingly intense closing number.

The aria is cruelly broken off, with

an extraordinarily bold

enharmonic change that takes the music

at one fell swoop into the very

distant key of E flat. (At the point

where the violins’ D sharps are

transmuted into their aural

equivalent, E flat, Haydn made his

intentions clear by writing the words

"N.B. the Same Tone" above the violin

part, much as he was to do on several

future occasions involving complex

notational key-switches of this kind.)

As for the concluding aria,it is a

wildly despairing Allegro in F minor

in which Haydn enriches his orchestral

palette by introducing the sound of

clarinets, while allowing the soprano

part to spread itself spectacularly

over a range of two octaves, to reach

high C at the final words, 'l'ecesso

del dolor' ('excess of grief').

Haydn had used clarinets for the first

time in his Symphony No.99, of 1793,

to add warmth to the music’s sonority.

In the cantata their presence lends

pungency to the expression of a state

of mind bordering on madness.Very few

of Haydn's minor-mode works of the

1790s actually retain the intensity of

the minor right up to the bitter end.

In this case, though, as in the great

F sharp minor Piano trio composed

around the same time, there is no

question of offering a placatory

resolution in the major, and the music

maintains its bleak atmosphere until

the very last bar.

Misha Donat

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|