|

1 DVD

- 101

327 - (c) 2008

|

|

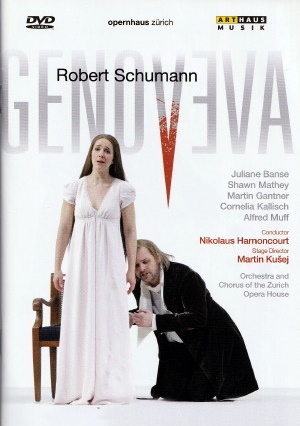

Robert Schumann

(1810-1856)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Genoveva |

|

|

| Oper in four Acts - Libretto

by Robert Reinick and Robert Schumann |

|

|

|

|

|

| Opening |

1' 04" |

|

| - Ouvertüre |

8' 15" |

|

| - Erster Aufzug |

35' 35" |

|

| - Zweiter Aufzug |

32' 57" |

|

| - Dritter Aufzug |

29' 01" |

|

- Dritter Aufzug

|

38' 11" |

|

| End

Credits |

1' 06" |

|

|

|

|

Juliane

Banse, Genoveva

|

Martin

Kušej, Stage Director |

|

Shawn

Mathey, Golo

|

Rolf

Glittenberg, Set Design |

|

Martin

Gantner, Siegfried

|

Heidi

Hackl, Costumes |

|

| Cornelia

Kallisch, Margaretha |

Jürgen

Hoffmann, Lighting |

|

| Alfred

Muff, Drago |

|

|

| Ruben

Drole, Hidulfus |

|

|

| Tomasz

Slawinski, Balthasar |

|

|

| Matthew

Leigh, Caspar |

|

|

| Doris

Heusser, (Supernumerary) |

|

|

|

|

Orchestra and Chorus of the Zurich

Opera House / Ernst Raffelsberger, Chorus

Master

|

|

| Extra Chorus and supernumeraries

of the Zurich Opera House |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Conductor |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Opernahaus,

Zürich (Svizzera) - febbraio 2008 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

Felix Breisach Medienwerkstatt

(Supported by SWISS RE)

|

Edizione DVD

|

| ArtHaus Musik - 101 327 - (1 dvd) - 166' 00" - (c)

2008 - (GB) DE-GB-F-SP-IT |

|

| Note |

SCHUMANN’S GENOVEVA

- A MODERN-DAY DRAMA OF THE SOUL

On

25th June 1850, Robert Schumann's only

opera, Genoveva, received its

first performance at Leipzig State

Theatre. It was a much-awaited event, as

Schumann, widely regarded as the leading

German instrumental composer, had set

his mind to the urgent task of creating

a national opera. However, despite the

efforts of the composer's supporters to

maintain interest in the work, the opera

was soon forgotten. When conductor

Nikolaus Harnoncourt first came across

Genoveva some 15 years ago (he

subsequently recorded a CD of it in

1996), he voiced the opinion that

”Genoveva is a work of art for which one

should be prepared to go to the

barricades”.

Harnoncourt sees the main reason why Genoveva

has not been recognised as a brilliant

composition and perhaps the most

significant opera written during the

second half of the 19th century, as

having much to do with the false

expectations attached to the work. ”You

mustn't look for dramatic events in this

opera. What it offers us is a glimpse

into the soul. Schumann was not

interested in creating something

naturalistic - he wanted to write a type

of opera in which the music had a

greater say.”

Schumann - according to Harnoncourt -

believed that Mozartean

theatrical dialogue in opera was not a

tradition that should be continued in

his day. It was therefore

only logical that the composer wrote -

indeed had to write - the Libretto

himself in order to achieve the desired

link between sounds and words.

Harnoncourt was convinced that Schumann,

with this opera, had not only written

some wonderful music but also

succeeded in "rediscovering the genre of

opera", and he asked his respected

colleague, Germanist Peter von Matt

to give his opinion on the Libretto,

which - like the libretti of Schubert's

operas - is usually dismissed as ”impossible”.

One

of the conclusions that von Matt

comes to in his analysis is that "in its

deep structure the libretto is like a

drama by Kleist - which is not

surprising given that Schumann enjoyed

reading the German author. At first

glance it is Genoveva who is innocent,

Golo is the wicked character and the

Count the noble one. At second glance,

though, everything begins to look rather

different. The Count represents the

rigid status quo, with its norms and

laws. ’You

are a German woman, do not complaint’ he

calls to his wife as he leaves her.

People have laughed at this statement

and taken it as a symptom of the

superficiality of the entire opera

forgetting that Schumann, who was well

versed in the works of writers such as

Heine and Hoffmann and had grown up with

Jean Paul, must have been aware of the

ideological stupidity of this statement,

The reactionary nature of this statement

to his wife, in fact, characterises the

real nature of the Count: He represents

the forces that in 1847/48

- the year in which Europe was set in

turmoil by a continental revolutionary

movement and Schumann was writing his

opera - represented the old world. His

abrupt order to his wife toreshadows the

brutality of the death sentence that he

will later utter.

The legend of Genoveva was well enough

known in the 19th

century for it to be unavoidable that

the opera should bear the name as its

title. But the effect of this was to

make the female role into the main

protagonist and her counterpart, Golo,

into a subsidiary figure. Genoveva is

the saintly heroine, Golo

the scoundrel who slanders and abuses

her. The male role appears merely to be

a dramatic device - the trivial villain

in a drama about martyrdom. In

fact, Schumann reverses the situation in

both literary and musical terms. Golo is

in reality the main figure in the opera.

He is essentially the free, creative,

complete artist and individual -

a knight, warrior, hunter and singer -

and it is as such that he presents

himself in his first major aria. However

this 'completeness' is split and

destroyed. He could have been everything

at one and the same time: artist,

thinker, man of action and lover - a

fulfilment of the classical dream of the

'complete person’, the idea of the

individual as described in Schiller's

essay On Grace and Dignity and

further developed by Kleist in his essay

on the Marionettentheater, in

which he describes the darker aspects in

his story of the boy pulling a thorn out

of his foot. Romanticism is, after all,

to a large extent a devastating

portrayal of the failure of this dream

of the complete person, a depiction of

the divisions and destructiveness, the

split personalities and madness, the

banishment into the desert and the

winter journeys. In

Schumann's treatment of the story, Golo

should be seen as one of the most

radical figures of this type.”

Director Martin Kušej

describes Golo as the one

single figure in the opera from whom

everything emanates, and here he sees a

close link with Schumann himself. He

regards the ‘poetical times‘

in which the composer sets the action as

without doubt being Schumann’s own

times, with the action taking place in

his head and his heart, his room, his

dreams, his immediate world, Clara, his

rigid, hostile father-in-law: ”I

see the work as being a thousand miles

away from this strangely distracting

crusader theme; I see it

rather as being rooted in the masses of

the 1848 revolution who joyously

proclaimed a new freedom and a new

religion - that of nationalism.

That is why I am convinced that a modern

production of Genoveva has to

derive its justification and its

interpretative approach from the

concrete circumstances that arose during

the time of its composition and that

still affect us even in the 21st

century, because they have still not

been resolved: nationalism and an

obsession with order, the psychological

effects of a discredited image of women,

motherhood and sexuality, fulfilment of

duty as a betrayal of love

(Siegfried-Genoveva) and, finally, the

great 'world rift' (Heine), that has

divided us and permanently destroyed our

’intactness’.”

According to the director the story "for

presentation on the stage needs to be

embedded in a context that moves it in

its entirety onto a completely different

plane, a completely different state of

mind. I think it is

necessary to find a clear temporal

framework in the early 19th

century ‘Biedermeyer’ period, the run-up

to the 1848 revolution

in Germany, or even in 'Romanticism'; at

all events in the period that directly

affected and surely also left its mark

on Schumann. He is the sensitive artist

and free-thinker in his bare, white room

in Dresden. It is the

year 1848 and we find

ourselves in an atmosphere of

indefinable darkness. Outside, the

masses are gathering for the uprising.

In the room are three further, strange,

black-clad figures, sitting there

inactively, like frozen ghosts. A man,

the master of the house, a female

servant, foreign-looking, menacing, and

a stunningly beautiful, pale-skinned

woman, on whom the main figure's

attention seems to be concentrated.

Everything that is about to happen

springs from the imagination and

feelings of these individuals,

especially from the tension between the

unconventional young man and the order

represented by the master of the house

(Siegfried). No-one is going to leave

this room.”

Set designer Rolf Glittenberg has

created two separate, clearly-defined

worlds as a structure for the work: an

inside space of dazzling, almost cutting

brightness and an external world that

seems to have no boundaries and is

defined in terms of impenetrable

darkness. The first world affects only

the four main figures: Golo,

Genoveva, Siegfried and Margaretha;

all the others belong to the second,

external world: Hidulfus, Drago,

Balthasar, Caspar and with them, the

entire world of servants, soldiers,

huntsmen and the common people. This

external world is an autonomous complex

with its own dynamics, but one that

again and again penetrates the white

space and triggers movement or change in

it.

Both conductor and director are

convinced that what Schumann created

with Genoveva was a drama of the

soul, an entirely un-classical work that

is thoroughly modern, indeed borders at

times on theatre of the absurd. The

opera raises questions without offering

any answers. It does

not intend to moralise, but rather to

portray something, for one cannot cure

the incurable. Schumann was concerned to

portray inner states, to show the

inevitability of events that at a

certain point generate an inescapable

dynamic. For this reason the opera takes

place outside all reality and beyond all

morality; the theme is the inevitability

of fate and - according to Nikolaus

Harnoncourt - ”the irreversible flow

that is represented by the music. Once

it has been set off, it can never be

stopped. The opera is one single massive

symphony. The entire work is made up of

a subtle network of motifs that are

largely derived from one single

leitmotif - the chorale at the outset,

which is then subject to different

variations. Initially it stands for

itself, as a pious chorale in the

positive sense, then it takes a turn to

the negative and becomes the pressure

exerted on the masses; then it becomes a

portrait of Golo,

depicting him as a positive figure; the

motif is then transferred to

Genoveva and, in slightly modified

form, comes to represent Margaretha.

This means, of course, that an

immensely strong link is created

between all the characters. We are

accustomed to leitmotifs

characterising single individuals. But

who says that has to be the case?

Schumann adopts a much more

sophisticated approach, maintaining

leitmotifs across all the figures. By

using them in a variety of different

combinations, they end up not

expressing one particular character

but rather the endless different

possibilities that lie in a single

character.

It would appear that

Schumann is not concerned about

theatrical personalities. The figures

do not explain their psychology, they

are not people but attitudes, aspects

of one personality, different facets

of one individual. So if we start

looking for theatrical characters, we

are barking up the wrong tree. The aim

of the composer is to portray a

situation and at the same time observe

its development. Everything is

inevitable. Aghast, one looks in the

mirror and sees in it the

conscientious fool, the virginal saint

and the inscrutable aspect that

everyone's personality has. What is

important here is not that a story is

being recounted that you have to

understand, but rather that you are

being confronted with yourself, you

are looking into a massive mirror that

enables you to comprehend yourself

better. For the Romantics especially,

an important aspect was the immediacy

and strength with which art was

experienced.”

At the heart of the opera lies the

scene in which Siegfried, with the

help of the enchanted mirror, tries to

convince himself of the guilt or

innocence of his wife. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt compares this scene with a

psychoanalysis session with Freud:

Does the individual wish to look into

the past and if so, can he bear to do

so? For Martin Kušej,

too, the mirror takes on a new

function here: in the opera it no

longer serves to deceive the unwitting

husband, but rather Siegfried uses it

because - thrown back on his own fears

and feelings - he feels deeply

unsettled. His 'memory fails'

- and he is no longer sure of his

feelings for Genoveva; thus his

imagination starts to conjure up its

own pictures of Genoveva's putative

adultery. He uses the mirror in order

to stabilise an orderly system - which

is already starting to crumble - in

which he "as a husband has a right to

a faithful wife" (Hebbel).

In Schumann's day the legend of the

saintly Genoveva was well-known and -

according to the director - "there was a

special background to this. It

was above all her 'holy' innocence that

made the text so popular. From the year

1800 onwards a significant increase

could be observed in the cult and

worship of the Virgin Mary, together

with a predominant discourse about the

concept of motherhood which, for

example, completely subordinated the

sexual urge to social morality. This

movement found, in the Virgin Mary (and

Genoveva), an ideal figure on which to

project its ideas. Mary was no longer a

mediator between Man and God but rather,

above all, a mediator between apparently

irreconcilable maxims of sexual

ideology, between purity, morality,

innocence - in other words, sexual

intactness - on the one hand and

motherhood on the other. The virgin and

mother made the impossible possible: a

de-sexualised form of motherhood.

The religious interests of men and women

were beginning to diverge. At the same

time the 'pressure for

marital harmony amongst the bourgeoisie'

was growing and received its expression

in the romantic ideal of love. The

construct of the 'affectionate pair' or

'affectionate female partner'

was regarded as a bourgeois ideal and,

as such, was closely linked to

patriarchy and Catholic piety. Genoveva

was practically a 'brand' to which

Schumann was deliberately putting

forward, albeit in subtle form, a strong

contrast; the opera portrays a

complementary world to that of Genoveva,

namely the chaos of the 'witch', who is

for me a mysterious and multi-facetted

figure. I see her as a sort of

servant/companion both for Golo

and the other two figures. In the

(dramatic) literature of the time one

often finds dark-skinned, wild 'slaves'

or counter-figures (e.g. in Grillparzer

or Grabbe) that symbolise above all the

unconscious, wild, unpredictable side of

the hero concerned." In 1849

Schumann wrote to Heinrich Dorn:

'Genoveva! But don't think in terms of

the old sentimental figure. I think it

is a piece of life history, as every

dramatic poem should be."

Ronny Dietrich

principal dramatic adviser at

the Zurich Opera House

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|