|

2 DVD

- 2054508

- (c) 2005

|

|

Henry Purcell

(1659-1695)

|

|

|

|

|

|

King Arthur

|

|

|

| A Dramatick Opera in Five

Acts - Libretto by John Dryden |

|

|

|

|

|

| Opening |

0' 26" |

|

| - No. 2 - Overture |

1' 57" |

|

| - "Hier ist's, wo

sie ihr heidnisch Wesen treiben" |

9' 59" |

|

| - No. 4 - Overture |

1' 34" |

|

| ACT I |

18' 52" |

|

| - "Wotan, höre uns!" |

5' 24" |

|

| - No. 5 - Recitative:

"Woden, first to thee" |

8' 56" |

|

| - No. 6 - Recitative: "The

white horse neigh'd aloud" |

|

|

| - No. 7 - Recitative: "The

lot is cast" |

|

|

| - No. 9 - Song & Chorus:

"I call ye all" |

|

|

| - "Der heiße, rote Saft

der Opfer tränkt die Erde" |

1' 17" |

|

| - No. 10 - Song &

Chorus: "Come if zou dare" |

3' 15" |

|

| - No. 11 - First Act Tune |

|

|

| ACT II |

36' 43" |

|

| - "'s ist Krieg! 's ist

Krieg!" |

1' 26" |

|

| - No. 3 - Air |

0' 45" |

|

| - "Wer bist du, Geist,

wes Namens und von welcher Art?" |

5' 46" |

|

| - No. 12 - Song & Double

Chorus: "Hither this way" |

2' 17" |

|

| - "Wohin nun führt der

Weg?" |

0' 58" |

|

| - No. 13 - Song: "Let not a

moon-born elf mislead ye" |

1' 45" |

|

| - No. 14 - Double Chorus:

"Hither this way" |

|

|

| - "Warum zieht dies

Gezirpe sie nur an?" |

0' 44" |

|

| - No. 15 - Septet &

Chorus: "Come follow me" |

3' 45" |

|

| - No. 16 - Song &

Chorus: "How blest are shepherds" |

4' 23" |

|

| - No. 17 - Duet: "Shepherd,

shepherd, leave decoying" |

3' 11" |

|

| - No. 18 - Chorus: "Come,

shepherds, lead up" & Hornpipe |

|

|

| - "Mein Arthur, sprich,

bist du zurück" |

8' 09" |

|

| - No. 1 - Chaconne |

3' 34" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 19 - Second Act Tune:

Air

|

1' 12" |

|

| ACT III |

48' 39" |

|

| - "Der Weg bis hierher

ist gesichert" |

7' 25" |

|

| - "We must work, we must

haste" |

2' 38" |

|

| - "Thus, thus I infuse" |

|

|

| - "Emmeline!" |

7' 02" |

|

| - No. 41 - Dialogue: "You

say, 'tis love" |

5' 35" |

|

| - "Mein Fürst, riskant

war es, so lang zu bleiben" |

5' 15" |

|

| - The Frost Scene |

6' 31" |

|

| - No. 20 - Prelude |

|

|

| - No. 21 - Recitative: "What

ho, thou genius of this isle" |

|

|

| - No. 22 - Song: "What power

art thou" |

|

|

| - No. 23 - Song: "Thou

doting fool" |

|

|

| - No. 24 - Song: "Great

love, I know thee now" |

|

|

| - No. 25 - Recitative: "No

part pf my dominion" |

|

|

| - No. 26 - Prelude |

10' 06" |

|

| - No. 27 - Chorus: "See,

see, we assemble" |

|

|

| - No. 28 - Song &

Chorus: "Tis I, 'tis I, that have warm'd

ye" |

|

|

| - No. 29 - Duet: "Sound a

parley" |

|

|

| - No. 28a - "Tis love, 'tis

love" |

|

|

| - "Gern erkenn ich deine

Künste an" |

3' 29" |

|

| - No. 30 - Third Act Tune:

Hornpipe |

0' 38" |

|

| ACT IV |

16' 04" |

|

| - Merlin's Intermezzo |

3' 30" |

|

| - "Arthur, ich hab dich

überall gesucht" |

3' 01" |

|

| - "Oh, was kommt denn

da?" |

3' 53" |

|

| - No. 31 - Duet: "Two

daughters of this aged stream" |

|

|

| - "Mir rieseln

Wonneschauer durch die Adern" |

5' 03" |

|

| - No. 33 - Fourth Act Tune:

Air |

0' 37" |

|

| ACT V |

28' 39" |

|

| - "Verflucht! Grimbald

gefangen und der Wald entzaubert!" |

1' 16" |

|

| - No. 43 - Song &

Chorus: "St. George, the patron of our

isle!" |

1' 43" |

|

| - "Gib dich geschlagen

und bitte um dein Leben" |

2' 40" |

|

| - No. 34 - Trumpet Tune |

1' 04" |

|

| - No. 42 - Trumpet Tune |

|

|

| - "Endlich, endlich halt

ich dich in meinen Armen" |

2' 53" |

|

| - No. 35 - Song: "Ye

blust'ring brethren of the skies" |

4' 13" |

|

| - No. 36 - Symphony |

|

|

| - No. 37 - Duet &

Chorus: "Round thy coasts" |

|

|

| - No. 39 - Song & Trio:

"Your hay it is mow'd" |

2' 29" |

|

| - No. 40 - Song: "Fairest

isle" |

3' 00" |

|

| - "Merlin, schlau hast

du nur, was uns gefällt, hier offenbart" |

0' 43" |

|

| - No. 32 - Song &

Chorus: "How happy the lover" |

6' 42" |

|

| Credits |

1' 56" |

|

|

|

|

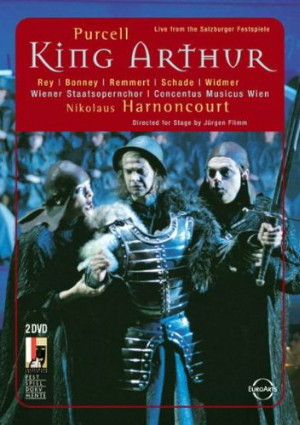

Isabel

Rey, soprano

|

Jürgen

Flimm, stage director |

|

Barbara

Bonney, soprano

|

Klaus

Kretschmer, stage design and

video |

|

Birgit

Remmert, contralto

|

Birgit

Hutter, costumes |

|

| Michael

Schade, tenor |

Manfred

Voss, lighting |

|

| Oliver

Widmer, baritone |

Catharina

Lühr, Choreography |

|

| Michael

Maertens, King Arthur |

Susanne

Stähr, dramaturgy |

|

| Dietmar

König, Oswald |

|

|

| Peter

Maertens, Conon |

|

|

| Christoph

Bantzer, Merlin |

|

|

| Roland

Renner, Osmond |

|

|

| Christoph

Kail, Aurelius |

|

|

| Sylvie

Rohrer, Emmeline |

|

|

| Ulli

Maier, Matilda |

|

|

| Alexandra

Henkel, Philidel |

|

|

| Werner

Wölbern, Grimbald |

|

|

|

|

| Konzertvereinigung Wiener

Staatsopernchor / Rupert Huber, chorus

master |

|

Concentus Musicus Wien

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, conductor |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Felsenreitschule,

Salzburg (Austria) - 24-28 luglio

2004 (A performance from the

Salzburger Festspiele) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Dietmar Schuler / Wolfgang

Bergmann |

Edizione DVD

|

| Euro Arts Music - 2054508

- (2 dvd) - 74' 00" + 95' 00" - (c) 2005

- ZDF/Arte (c) 2004 - (DE) GB-DE-FR-IT |

|

| Note |

|

King Arthur is a

work that defies categorization. A

collaboration between Henry Purcell and

John Dryden, it is a

hybrid piece, half spoken drama, half an

opera made up of seven musical tableaux.

The plot concerns Arthur, the legendary

king of the Britons, and is advanced in

the spoken dialogue, while the music

provides the allegorical trimmings. As a

result, the singers do not play

particular roles but keep changing,

appearing as gods, shepherds, nymphs and

even as a referee in a boxing match. But

neither of these two genres, spoken

drama or opera, would be conceivable

without the other in this work.

In

attemping to define this strange beast,

Nikolaus Harnoncourt has described King

Arthur as “the first musical in

history”, for the work contains not only

singing and spoken dialogue but also a

great deal of dancing. And, as in every

good musical, the plot involves a love

story: Arthur, the king of the Britons,

loves beautiful blind Emmeline, but

Oswald, the king of the Saxons, loves

her, too. The result is war, The love

intrigue is at the heart of the piece,

but the rivalry between the two kings

also symbolizes the battle not only

between their two nations, namely, the

Britons and the Saxons, but also between

their two religions: the Britons are

decent Christians, while the Saxons

still believe in Woden, Thor and Freya.

But all these quarrels are spiced up by

the intervention of spirits, with each

of the warring factions having at its

disposal a magician and a spirit of the

air or earth that keep trying to outdo

each other, with art pitted against art,

and magic against conjuring tricks.

First

performed at the Queen’s Theatre, Dorset

Garden, in 1691, King Arthur is

a typical product of the British

Baroque. Not to put too fine a point on

it, the Britons of that period were a

nation of grumpy old men where opera was

concerned: "Experience hath taught us

that our English genius will not rellish

that perpetual Singing," we

read in the Gentleman's

Journal in January

1692. Audiences preferred gaudy stage

spectacles offering a variety of genres.

Nor were librettists particularly

fastidious in their taste: plots had to

be amusing and true to life but they

also had to contain a hint of frivolity,

slapstick humour and sensational and

even gruesome effects: there were

burning temples and lowering storms,

including thunder and lightning, wind

and rain, in which entire fleets of

ships would be lost, and in the case of

monumental battles such as the one that

begins King Arthur, Dryden, A a

true man of the theatre fully aware of

what was effective onstage - would equip

his performers with sponges soaked in

blood in order to ensure that the full

horror of the scene was given its due.

All

these aspects were taken into account by

Jürgen

Flimm and Nikolaus Harnoncourt when they

set about devising a concept for their

Salzburg production of King Arthur.

First, however, they had to come up with

a performing version: there is no

surviving full score offering a

definitive version of the work or

containing either a clear running order

of the individual numbers or an

indication as to their instrumentation.

Purcell’s music has survived only in

sixty scattered and in part

contradictory sources. Only Dryden’s

wordbook can offer any guidance, yet it

is clear that not even Purcell himself

felt bound to adhere to it exactly: the

surviving material also includes

settings of words that are not by Dryden

at all. The Salzburg version goes back

to Dryden’s original libretto, but in a

new translation: the spoken dialogue is

performed in German, while the musical

numbers are sung in English. Blocks of

music and dialogue are arranged in such

a way as to produce a sensible and

well-balanced interplay between them.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt instrumented

the music for his own orchestra, the

Concentus Musicus, and his wife, who

plays the violin in the orchestra,

prepared a manuscript part for each

individual player.

King

Arthur is a masterpiece of the

Baroque theatre and so it was only

fitting that it should be performed in a

Baroque building in Salzburg, the

Felsenreitschule, which dates from 1693

and which once housed equestrian games

and hunts. This Baroque playing area

provides the starting point for the

sets: spectators can see the famous

arcades, but they can also see through

them, with the result that the arcades

function as windows affording a glimpse

of other worlds. How is this done? A

second arcaded wall, made of wood, was

erected in front of the stone wall. It,

too, was three storeys high and was

accessible to the performers. The

artificial wall served as the acting

area, while the stone wall was covered

in cloths. And behind these cloths were

sixty-seven video projectors that

allowed whole landscapes and other

images to be projected on to them from

behind: the result was a theatre of

magic using the resources of the 21st

century.

In

the subtitle of his libretto, Dryden

described King Arthur as

"adorn’d with Scenes, Machines, Songs

and Dances", and these machines

-including even authentic Baroque

machines - were naturally used in the

present production, with Baroque flying

machines rising to the occasion whenever

the spirits work their wonders: for his

scene in Act II, for

example, Merlin flies in on a surfboard,

while Philidel, the spirit of the air,

performs a graceful aerial ballet;

Cupid, the god of love, soars through

the air, and Grimbald, the evil spirit

of the earth, is finally burnt up in the

air - the air is not, of course, his

native element, as he comes from hell,

appearing through trapdoors in the stage

floor to the accompaniment of

sulphurous, musty smells and dry ice.

Some of the episodes in this production

were improvised by the actors, notably

when the spirits appear and try to trick

one another. Spectators may be reminded

of the commedia dell'arte

tradition, and Merlin and Philidel,

Crimbald and Osmond certainly have

points in common with the servants of

the Italian improvised theatre inasmuch

as they, too, are the helpers and

accomplices of their respective masters.

And

finally there is the orchestra and its

conductor, all of whom are placed not in

the orchestra pit but in the middle of

the stage, in a circular depression. The

acting takes place not only behind, in

front of, to the side of, and above the

orchestra but even within it. Even more

remarkably, Nikolaus Harnoncourt and his

players also take part in the action.

The conductor not only hands the actors

their props ("Mr

Harnoncourt, do you happen to have a

sword on you?"), but he

also wears a bobble cap during the Frost

Scene and, together with his players,

underscores certain bits of magic

business. The climax comes in Act

V, during the grand

finale. Here Nikolaus Harnoncourt, one

of the gurus of the early music scene

and a prophet and pioneer of period

performing practice, conducts the

drinking song "Your hay it is mow’d"

as if the tenor Michael Schade were a

rock star and the Concentus Musicus his

band, with percussion aplenty and a

pounding beat. Technology provides a

colour organ, and everyone on stage can

join in the chorus - and

that includes the audience, too.

Susanne Stähr

(Translation:

Stewart Spencer)

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|