|

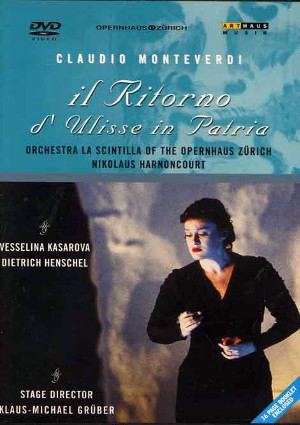

1 DVD

- 100 352 - (c) 2003

|

|

Claudio Monteverdi

(1567-1643)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Il Ritorno d'Ulisse in

Patria

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prologo:

L'Humana fragilità, Tempo, Fortuna, Amore

|

9' 58" |

|

Atto primo

|

62' 17" |

|

| - Scena I: Penelope,

Ericlea |

7' 24" |

|

| - Scena II: Melanto,

Eurimaco |

7' 38" |

|

| - Scena III: Melanto,

Penelope |

4' 40" |

|

| - Scena IV: Nettuno,

Giove |

7' 16" |

|

| - Scena V: Feaci,

Nettuno |

2' 52" |

|

| - Scena VI: Ulisse |

4' 38" |

|

| - Scena VII: Minerva,

Ulisse |

9' 39" |

|

| - Scena VIII: Eumete,

Iro |

3' 11" |

|

| - Scena IX: Eumete, Ulisse |

3' 29" |

|

| - Scena X: Telemaco,

Minerva |

2' 57" |

|

| - Scena XI: Eumete, Ulisse,

Telemaco |

4' 50" |

|

| - Scena XII: Ulisse,

Telemaco |

3' 43" |

|

| Atto secondo |

73' 01"

|

|

- Scena I: Melanto, Eurimaco

|

2' 14" |

|

| - Scena II: Antinoo,

Anfimono, Pisandro, Penelope (Ballo) |

10' 11" |

|

| - Scena III: Eumete,

Penelope, antinoo, Anfinomo, Pisandro,

Eurimaco |

5' 50" |

|

| - Scena IV: Antinoo, Eumete,

Iro, Ulisse, Antinoo, Penelope, Anfinomo,

Pisandro, Telemaco |

20' 07" |

|

- Scena V: Iro

|

6' 31" |

|

| - Scena VI: Minerva,

Giunone, Giove, Nettuno, Coro |

8' 21" |

|

- Scena VII: Ericlea

|

4' 23" |

|

- Scena VIII: Penelope,

Eumete, Telemaco

|

5' 14" |

|

- Scena IX: Ulisse, Penelope

|

10' 10" |

|

|

|

|

Dietrich Henschel,

L'Humana fragilità, Ulisse

|

Jonas Kaufmann,

Telemaco

|

|

Reinhard Mayr,

Antinoo

|

Martin Zysset,

Pisandro

|

|

Malin Hartelius,

Melanto

|

Martin Oró, Anfinomo

|

|

Isabel Rey, Minerva,

Amore

|

Boguslaw Bidzinski,

Eurimaco

|

|

Anton Scharinger,

Giove

|

Thomas Mohr, Eumete

|

|

Pavel Daniluk,

Nettuno

|

Rudolf Schasching,

Iro

|

|

Vesselina Kasarova,

Penelope

|

Cornelia Kallisch,

Ericlea

|

|

Martina Jankovà,

Fortuna, Giunone

|

Giuseppe Scorsin,

Tempo

|

|

|

|

ORCHESTRA LA SCINTILLA from

the Zurich Opernhaus

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Conductor |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Opernhaus, Zurich (Svizzera) -

2002 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| Live |

Producer / Engineer

|

Bel Air Media, François Duplat

/ ZDF Arte / Mezzo / Zurich Opera / NHK

|

Edizione DVD

|

| Art Hau Musik - 100 352 - (1

DVD) - 155' 00" - (c) 2003 - IT-DE-GB-FR-SP |

|

|

Notes

|

Il

Ritorno

d'Ulisse in

Patria: A

Quantum Leap

in Musical

History

Claudio

Monteverdi is known as the

father of opera - a

commonplace tag, perhaps,

but one which has taken root

in the history of music

theatre and brought into

sharper focus the true

historical circumstances.

Opera, of course, existed

before Monteverdi, but in a

wholly different context.

During the Italian

Renaissance, for example,

musical pastorals with their

idealised Arcadian scenes filled

the courts of feudal lords.

Such exclusive circles were

lavish to the point of

wastefulness in their

celebration of these

operatic precursors;

nevertheless they prepared

the way thematically and

musically for the

development of a bourgeois

opera culture in northern Italy. And

at precisely this moment -

early in the seventeenth

century - the genius of

Claudio Monteverdi arrived

on the scene.

The Teatro San Cassiano in

Venice opened its doors to

the public in 1637

and in so doing became the

world's first

commercial opera house. It

was a ‘Temple of the Muses’

for all those that could

afford the price of a ticket

and was thus independent of

the patronage of generous

princes. Early performances

would have seemed rather

carnival-like in atmosphere

by today's standards; but it

was not long before a new

type of music theatre began

to crystallise. Real

characters populated the

stage - a cast list drawn

from gods and mortals,

allegorical figures and

burlesque freaks. The

libretti were colourful,

multi-layered and, in terms

of musical style, required a

handamerital change of

approach. The fashion was no

longer for the pure,

ethereal sounds of the

polyphonic Renaissance

madrigal; it was now the

turn of recitative.

Reduction of musical forces

to just a few accompanying

instruments was not done

merely for economic reasons.

It

was in line with the newly

perceived necessity to place

the text in the foreground.

Music, it was said, served

to illustrate and therefore

followed the word in

emphasis and metre. In

declamatory passages only

the vocal and bass lines

were written out, leaving

the chords to be filled out

by the musician during the

performance - a convention

which continued until well

into the Baroque period, and

one which has presented

certain problems for modern

performance practice. A more

opulent orchestration was

reserved for the musical

interludes and aria-like

passages, the richer sounds

supposedly adding the

required gravitas.

"Il

Ritorno d'Ulisse in

Patria" was Monteverdi's

first opera for the new

opera house; it was

performed there in

1640/41. In terms of its

virtuoso perfection as a

"Dramma in musica" it

comes rather as a bolt

out of the blue.

Compared with Monteverdi's

first opera, "L'Orfeo",

composed 33 years

earlier, this Homer

adaptation is worlds

apart. Whereas "L`Orfeo"

- with its

Renaissance-like

pastoral madrigals - was

still firmly rooted in

the courtly tradition,

the music of "Il

Ritorno" is completely

dominated by the

recitative style known

as "monody".

Of course, Monteverdi's

groundbreaking approach

to opera did not come

about in a moment of

inspiration; rather it

was the culmination of

an evolutionary process.

But it is difficult today

to piece together this

process. From his opera

"Arianna" (Ariadne) only

the famous "Lamento"

remains extant, and a

further six works have

been lost without trace.

The route he took to

arrive at this

monodistic style of

writing thus remains

rather obscure. Viewed

from this perspective,

Monteverdi’s late works

such as "ll

Ritorno" (not

rediscovered until 1878)

and "L'Incoronazione

di Poppea"

stand out as being all

the more uniquely

innovative as a result

of the incompleteness of

the evolutionary

process.

"Ulysses"

- The Odissey of an

Opera

For 240

years nothing was known

of Monteverdi's Odysseus

opera, a work based

closely on books 15 to

23 of Horner’s epic

poem. But it did not

take long after the

opera's rediscovery for

it to be hailed as a key

work marking the

threshold between the

Renaissance and Baroque

periods. Attempts to

fathom the score,

however, presented all

sorts of difficulties.

The musical notation

gave only the two outer

parts (voice and bass),

a practice which misled

musicologists of the day

into thinking the score

to be rudimentary and

incomplete in nature.

Not until the more

exhaustive source

studies of the twentieth

century did the true

circumstances come to

light. Monteverdi’s

performances relied on

the skills of musicians

who were able to fill out

the chords from a

figured bass as the

dramatic action

required. Moreover, this

concise form of notation

presumably also meant

the composer was able to

prevent “pirate copies”

of his work from being

made, since only he and

his circle of musicians

would have known the

detail of the

performance.

This, too, is

precisely where the problems

start for a modern

performance. we have

Nikolaus Harnoncourt to

thank for the fact that a

musicologically sound - if

ultimately ‘unofficial’

- catalogue of conventions

for Monteverdi performance

practice has survived until

the present day. The

conductor developed his

theories about authentic

instrumentation from a wide

range of sources.

"We

used the same

instruments that would

have been in use in

Italy at the time -

stringed instruments

belonging to the violin

family, four recorders

to add grace and

brilliance to certain

scenes, two piffari

(soprano shawms) and a

dulcian for pastoral and

comic passages. And we

introduced trumpets and

trombones -

a regular contemporary

practice common whenever

the gods made an entry -

to accompany Neptune and

at moments of solemnity.

These melodic

instruments - also used

at times as solo

instruments - were

supported by a plethora

of continuo instruments,

including a large

Italian harpsichord, a

small virginal, two

lutes, a chitarrone,

organ, harp and

regal..." (N.

Harnoncourt)

The

spectacular success enjoyed

by this opera 25 years ago

at the Zurich Opera was due

in no small measure to the

breadth of tonal colour

achieved by this amazing

ensemble of instruments. Jean-Pierre

Ponnelle’s ingenious staging

was accompanied from the

orchestra pit by raspings,

Whistlings and strummings,

the like of which no

opera-going public had heard

before. The exuberance of

his scene setting, the

strangely florid music and a

first class cast of singers

turned "Il Ritorno" and the

other productions of

Harnoncourt's legendary

Monteverdi cycle into

triumphs and milestones of

historic performance

practice. These productions

subsequently went on tour to

all the major international

opera houses, were recorded

on film and are still

considered today to be

Ponnelle’s most outstanding

achievements.

The musical world

had woken up to Monteverdi’s

early Baroque masterpieces.

But precisely because of the

diverse possibilities of

interpretation, these operas

were always going to lend

themselves to any number of

new adaptations and

realisations. Hans Werner

Henze`s "Il Ritorno",

for example, performed on

the great opera stage of the

1985 Salzburg Festival

(produced by Michael Hampe).

Or René Jacob`s

opulent orchestration of

“Orfeo” - a festival

celebrating the purity of

sound. And Harnoncourts

anniversary production of

“Ulysses” in Zurich, which

is anything but a revival.

Together with producer Klaus

Michael Grüber,

Harnoncourt strikes a new

balance between musical

polish and distillation of

the essence of dramatic

action. "It is a kind of

‘théâtre

pauvre’, which works with

a few carefully chosen and

powerful symbols”,

was how the newspaper Neue

Zürcher

Zeitung reviewed the

production. The main

action takes place on

little more than an angled

revolving stage in front

of a whitewashed wall

which hints at the

landscape of a Greek

island. Irus,

the comical glutton, is

cast as a theatre director

and has Penelope's ghastly

suitors line up alongside

one another as marionettes

in a puppet show - a

producers whim which gave

rise at the time to all

kinds of speculation as to

the current fate of music

theatre.

Harnoncourt's

musical drive has become

"a touch gentler", wrote

the Berlin daily

Tagesspiegel. “Not that

Harnoncourt is now leaving

things to chance or to the

discretion of his

exquisite musicians. But

the way he communicates -

his entire rostrum manner

- seems to have become

more relaxed, calmer,

rounder, and both

he and the listener are

amply rewarded by

the sound which results.”

The Gods

Must be Crazy - The

Odyssey Comes to an End

In

the prologue to the opera,

the Libretrist Giacomo

Badoaro establishes the fact

that humankind is but a

helpless plaything in the

hands of the superior forces

of Time, Fortune and Love.

But it is soon apparent that

man shares his lot with the

gods, for they, too, are

forced to face life's

vicissitudes - the

only difference being that

the gods are immortal.

Whilst

Penelope sings a moving

lament for the absence

ofhei' husband Odysseus, it

is clear their two fates

have long since become a

bone of contention among the

gods. Neptune reproaches Jupiter

for having Shown his sworn

enemy Odysseus

the way

back to Ithaca. When

Odysseus lands there,

Minerva disguises him as an

old beggar in order to

protect him from his

pcrsecutors. Meanwhile,

Penelope is forced to fend

off the advances of three

suitors, each

of whom

are brazenly out to win her

hand. To make matters worse,

she is forced

to endure the impudence of

the glutton

Irus,

whose aim is to turn this

desperate situation to his

advantage.

In

Act Two, Odysseus' son

Telemachus receives news of

the return of his father.

His mother's suitors become

more importunate and plot to

murder Telemachus. In

desperation, Penelope

finally promises to choose

as her husband whichever

man successfully strings

Odysseus' bow. The only one

capableof this feat,

however, is the old beggar,

who then swiftly and

unhesitatingly slays the

shameless suitors.

Act Three begins with the

suicide of Irus,

who was certain he would

starve without

the support of the three

suitors. Penelope refuses to

believe the true identity of

the old beggar. Once again

the gods intervene - Minerva

asks Juno

for help, who together with

Jupiter

is able to soothe Neptune's

hatred and in so doing

prepare the way for the

“lieto fine”, the happy

ending. Penelope, however,

is still unable to overcome

her grief. Only when the old

beggar is able to describe

the finely

woven

blanket that once covered

their marriage bed does she

finally recognise him for

who he is.

Wolf-Christian

Fink

(Translation:

Alan Seaton)

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|