|

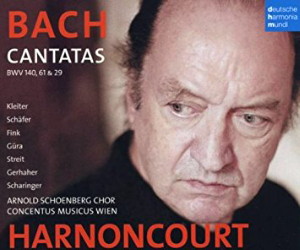

2 CD -

88697 56794 2 - (p) 2009

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cantatas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cantata "Wachet auf,

ruft uns die Stimme", BWV 140 (1731)

|

|

27' 48" |

|

| Solo: Sopran, Tenor, Bass - Chor |

|

|

|

| Corno, Oboe I/II, Taille,

Violino piccolo, Violino I/II, Viola,

Continuo |

|

|

|

| - Coro: "Wachet auf,

ruft uns die Stimme"

|

6' 56" |

|

CD1-1

|

| - Recitativo (Tenor): "Er

kommt, der kommt" |

0' 58" |

|

CD1-2

|

| - Aria (Duetto: Soprano,

Bass): "Wann kömmst du, mein

Heil?" |

5' 52" |

|

CD1-3

|

| - Corale: "Zion hört

die Wächter singen"

|

3' 57" |

|

CD1-4

|

| - Recitativo (Bass): "So

geh herein zu mir" |

1' 29" |

|

CD1-5

|

| - Aria (Duetto: Soprano,

Bass): "Mein Freund ist mein" |

6' 33" |

|

CD1-6

|

| - Choral (Coro): "Gloria

sei dir gesungen" |

1' 53" |

|

CD1-7

|

Cantata "Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland", BWV 61 (1714)

|

|

14' 11" |

|

| Solo: Sopran, Tenor, Bass - Chor

|

|

|

|

| Violino I/II, Viola I/II,

Violoncello, Fagotto, Continuo |

|

|

|

| - Coro: "Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland" |

3' 23" |

|

CD1-8

|

| - Recitativo (Tenor): "Der

Heiland ist gekommen" |

1' 25" |

|

CD1-9

|

| - Aria (Tenor): "Komm, Jesu

komm zu deiner Kirche" |

3' 45" |

|

CD1-10

|

| - Recitativo (Bass): "Siehe,

ich stehe vor der Tür" |

1' 00" |

|

CD1-11

|

| - Aria (Soprano): "Öffne

dich, mein ganzes Herze" |

3' 47" |

|

CD1-12

|

| - Choral (Coro): "Amen,

amen!" |

0' 51" |

|

CD1-13

|

Cantata "Wir danken

dir, Gott, wir danken dir", BWV 29

(1731)

|

|

21' 44" |

|

| Solo: Sopran, Alto, Tenor, Bass

- Chor |

|

|

|

| Tromba I/II/III, Timpani, Oboe

I/II, Violino I/II, Viola, Organo

obligato, Continuo |

|

|

|

| - Sinfonia |

3' 38" |

|

CD1-14

|

| - Coro: "Wir danken dir, Gott,

wir danken dir" |

2' 20" |

|

CD1-15

|

| - Aria (Tenor): "Halleluja,

Stärke und Macht" |

5' 36" |

|

CD1-16

|

| - Recitativo (Baritone): "Gottlob!

es geht uns wohl!" |

0' 48" |

|

CD1-17

|

- Aria (Soprano): "Gedenk an

uns mit deiner Liebe"

|

5' 14" |

|

CD1-18

|

| - Recitativo (Alto &

Chorus): "Vergiss es ferner nicht" |

0' 25" |

|

CD1-19

|

| - Aria (Alto): "Halleluja" |

1' 41" |

|

CD1-20

|

| - Choral (Coro): "Sei Lob

und Preis mit Ehren" |

2' 02" |

|

CD1-21

|

| Cantata "Wachet auf,

ruft uns die Stimme", BWV 140 (1731) |

28' 29" |

|

CD2-1/7

|

| Cantata "Nun komm, der

Heiden Heiland", BWV 61 (1714) |

14' 39" |

|

CD2-8/13

|

| Cantata "Wir danken

dir, Gott, wir danken dir", BWV 29

(1731) |

23' 33" |

|

CD2-14/21

|

|

|

|

|

| Julia Kleiter,

Soprano (BWV 140)

|

Werner

Güra, Tenor (BWV 61, 29)

|

|

Kurt Streit,

Tenor (BWV 140)

|

Gerald

Finley, Bass (BWV 61) |

|

| Anton Scharinger,

Bass (BWV 140) |

Bernarda

Fink, Alto (BWV 29) |

|

| Christine

Schäfer, Soprano (BWV 61,

29) |

Christian

Gerhaher, Baritone (BWV 29) |

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master |

|

|

|

Concentus Musicus

Wien

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone

|

|

-

Annette Bik, Violin (BWV 29)

|

-

Hermann Eisterer, Violone (BWV 61) |

|

-

Andrea Bischof, Violin (BWV 61)

|

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone (BWV 29) |

|

-

Annelie Gahl, Violin (BWV 29)

|

-

Robert Wolf, Flute (BWV 61) |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violin |

-

Reinhard Czasch, Flute (BWV 61) |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violin |

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe, Oboe

d'amore |

|

| -

Silvia Iberer, Violin |

-

Elisabeth Baumer, Oboe, Oboe da

caccia (BWV 61) |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel-Vock, Violin |

-

Barbara Urthaler, Oboe, Oboe da

caccia (BWV 61) |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violin |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe, Oboe

d'amore |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich, Bassoon (BWV 61) |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter Jun., Violin |

-

Milan Turkovic, Bassoon (BWV 29) |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi, Violin |

-

Hector McDonald, Horn (BWV 29) |

|

| -

Irene Troi, Violin |

-

Georg Sonnleitner, Horn (BWV 29) |

|

-

Mary Utiger, Violin (BWV 61)

|

-

Andreas Lackner, Trumpet (BWV 61) |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, Viola |

-

Wolfgang Gaisböck, Trumpet |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus, Viola |

-

Herbert Walser, Trumpet |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, Viola |

-

Franz Landlinger, Trumpet (BWV 29) |

|

-

Lynn Pascher, Viola (BWV 61)

|

-

Dieter Seiler, Timpani |

|

-

Dorle Sommer, Viola (BWV 29)

|

-

Herbert Tachezi, Harpsichord |

|

| -

Rudolf Leopold, Violoncello (BWV

61) |

Continuo: |

|

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello (BWV

29)

|

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello (BWV

61) |

|

-

Max Engel, Violoncello (BWV

61)

|

-

Leopold Rudolf, Violoncello (BWV

29) |

|

| -

Dorothea Schönwiese, Violoncello |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Organ |

|

-

Peter Sigl, Violoncello (BWV

29)

|

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

Musikverein, Vienna (Austria):

- 8 & 9 dicembre 2006 (BWV 61)

- 13 & 14 gennaio 2007 (BWV 29)

- 15 & 16 dicembre 2007 (BWV 140) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Martin Sauer / Michael

Brammann / Tobias Lehmann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi -

88697 56794 2 - (2 cd) - 63' 33" + 66'

41" - (p) 2009 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

Nota

|

| Interessante accostamento

interpretativo di tre Cantate: BWV 61

(1976/2006), BWV 29 (1973-74/2007) e BWV

140 (1984/2007). |

|

|

Notes

|

NIKOLAUS

HARNONCOURT

TALKS ABOUT THE BACH

CANTATAS

What does Bach's music mean to

you, Mr. Hamoncourt? And how did

your love of Bach actually begin?

The only work by Bach that I knew as

a child was the St. Matthew

Passion. I actually joined a

church choir so that I could sing in

it. I also played the Bach cello

suites when I was 10

or 11. But when

someone asked me what Bach meant to

me, I replied that he was a

mathematician, and that this wasn't

truly great music! The same person

wanted to know who my favourite

composer was, and I promptly

answered -

Grieg. Today, of course, I can't

understand how I could possibly have

thought that! But

in the St. Matthew

Passion there were passages

that touched me more deeply than any

other music I knew - the very last

suspension, or the first notes

played by the oboe in "Ich will bei

meinem Jesu wachen".

That is a line where you can

literally hear the watchman guarding

the city wall, and the metaphor is

extended to keeping watch over

someone who is sick, or who does

something wonderful during the

night.

While I was at music college between

1948 and 1952, I met up with a small

group of fellow students once or

twice a week, and we played our way

through the entire college library

together, from Perotinus to

Hindemith and Stravinsky. The size

of the ensemble varied from five to

twelve musicians, and one or two

singers often joined us as well.We

played arias from the Bach cantatas,

and realised in the process that the

performers in Bach’s time used

different instruments. This was the

period when I came to see sooner or

later that Bach is simply the

composer, a man head and shoulders

above the other really great

composers. Twenty or so years later,

I would be saying that there were

two such truly outstanding composers

- Bach and Mozart.

This is music where I want to hear

every last note that they wrote; I

shall always be moved by their

music, and will never really grasp

the fact that the authors of these

works of genius were mere mortals.

The fact is, Bach and Mozart weren't

mortals - their pens were directed

by some higher force. This convinced me

that henceforth I had one single

responsibility, namely to place

myself in their service.

We played The art of Fugue

on four viols while we were still

students, and spent an entire year

rehearsing it

first! When we founded the Concentus

Musicus Wien, we

resolved not to play any Bach at all

for the first couple of years - we

didn't feel we had attained the

necessary skill as yet. Only a few

years later did we play the Triple Concerto

together with Gustav Leonhardt, our

new flautist and my wife. After that

we gradually found our way to the

vocal works, culminating in the 1963

recording of the St. John

Passion with the Leonhardts in

Berlin. After that, we played

concertos and all manner of

otherworks by Bach.

You're

not someone who aspires to

'complete coverage' of any

particular composer - yet you

have performed and recorded the

complete Mozart

symphonies, and the complete Bach

cantatas. Why all of

them? In

the case of the cantatas, one

might argue that this was

primarily functional music,

written for use in church

services.

From the moment when I learnt to

distinguish the truly great geniuses

from their less inspired colleagues

- from "second-rank

geniuses", if you will - I realised

that a true genius doesn’t let a

single note reach the public that

fails to fulfil the very highest

standards. When we started playing

the Bach cantatas, we performed a

few in concert that were quite new

to us. And we were amazed by the

fact that a composer can write and

perform a new cantata every single

Sunday of the year! Then the

producer Wolf Erichson suggested

that we record all the cantatas in a

kind of Bach edition. This project

entailed all kinds of

problems, and we were fascinated by

the idea of solving them. The score

specifies "oboe da caccia"-

what kind of instrument is that?

Another passage calls for a "taille";

that’s an oboe tuned in F. But the oboe

da caccia is also an oboe tuned

in F. So why do they have two

different names? \/\/hy does the term

"como" appear over so many cantus

firmi? What is that supposed to

mean? Is it a type of

instrument? Or does it indicate that

that the cantus firmus requires

something else at this point? We found

ourselves stumbling from one tricky

question to the next. Fortunately for

us, Vienna has a superb musical

instrument museum, and that helped us

solve such questions.

One thing I didn't

realise when we made the first

recordings was that there is a radical

difference between the notation of a

work (NH: "Spiel-Notation") and the

playing instructions (NH:

"Spiel-Notation"). In Bach scores, you

find both. He

writes conventional notation in the

score, although the performer is not

intended to play what he sees on

paper: a dissonance that disrupts the

overall beauty must not find its way

on to paper; a suspension is called

for. A long note that is present in

the harmony, but isn't supposed to be

audible; it is written

as a long note, but played as a short

one.The articulation of the strings

isn’t written down at all - the

musician himself knows best how to

play it. But on some occasions, Bach

writes out the articulation precisely.

Now you have to ask

yourself whether the works where the

semiquavers don't have any slurs

should be played without slurs, while

the works where they have slurs should

be played with slurs? But they are

exactly the same figures! That prompts

me to say that one version is aimed at

knowledgeable musicians, but when the

performers were to be students, or

pupils from St.Thomas's School who

didn’t possess the requisite

knowledge, Bach made sure to write out

every tie, and from this we can learn

how he intended the other works to be

played that don’t have these slurs.

Contrary to your earlier

custom, you transposed BWV 61

upwards by a tone for this

recording, to B minor. Why?

In Weimar a high

choir pitch was in use, and you can

hear that the vocal parts in the

Weimar cantatas are differently

pitched; there are notes in the scores

that were not singable in the Leipzig

cantatas. The problem of the tuning

pitch of organs is an interesting one:

the cantata can either be written in

the key of the organ, or it can be

written in the key that the composer

wants, and the organ is then

transposed accordingly. This Bach did

later on in Leipzig, where the organ

parts are notated with the key

transposed. But an organ, too, can

have a lower register, a so-called

Musizier-Gedackt,

that was only used for the continuo

accompaniment. Bach tried various

solutions to this problem, and as a

performer you have to find out time

after time why the vocal parts are so

high in one cantata and so low in

another. It's simply not

possible today to organise an organ

tuned to a different pitch for each

cantata that we perform in concert, so

we proceeded along similar lines to

Bach when he performed a Weimar

work again in Leipzig: on such

occasions, he transposed the cantata

so that it could be performed in the

same pitch as it had been in Weimar.

Why do you prefer

working with a modern mixed choir

nowadays rather than with a boys' choir?

The explanation is simple: boys’voices

are breaking at an increasingly early

age these days. Where the children in

a boys’ choir are so young that most

of them have no idea what they’re

singing, the result is either a

childlike sound, or the message that

the music conveys is childlike. Some

people like this a lot, but I don’t -

it contradicts the seriousness and

depth of the music. Or you decide not

to wait forever until you find a choir

that happens to consist of country

children whose voices break later, and

opt for a mixed choir instead.

Listening again to your old

recording, I couldn't help but

notice that there used to be a lot more

pathos in the singing. Today,

everything is sung and in a much

more natural style.

I once sat down with a German theatre

scholar and listened to the same

monologue by the Austrian playwright

Grillparzer in all the recordings made

between 1908 and 1995. The

early recordings were literally oozing

with pathos, but at the time people

didn't feel the pathos to be at all

excessive, it was simply the spoken

style of early 20th century

theatre. As time passed, the language

became more natural, the pathos was

reduced, and the rhymes were clearly

enunciated. And a generation after

that,the audience wasn't supposed to

hear the rhyme at all, it was supposed

to sound like natural speech. So

personally, I would attribute part of

this difference to the spoken style

currently in vogue. In the meantime

there are older singers who have

changed their style in the course of a

longer career, and as a matter of

fact, so have we. At the outset, we

all believed that the old instruments

can teach us a great deal: What

can you play on these instruments?

What kind of sound do they call for?

But at the same time we were always

aware that the man blowing into the

mouthpiece is a 20th century

man, and the sound produced is not a

Baroque sound, but a 20th century one.

It's quite wrong to think that we are

trying to reproduce the performances

of Bach's own

time. I suspect Bach would laugh out

loud if he could hear us! But of

course he might like what he heard, he

might find it interesting. To be

honest, I imagine

Johann Strauß would laugh as well if

he heard us play,

simply because of changing fashion. I

don't see fashion as something

negative myself, to me it consists in

a constant and dialectic change.

One point is that our present-day

point of view is closer to the

original. Another is that we had to

learn this language from scratch when

we started out: we didn't know what

role rhetoric plays, and it never

featured on the curriculum at music

college.What exactly

does it mean to say that music follows

the rules of language, and just how

does it do so? We found

some answers in historic teaching

manuals that even transferred figures

from rhetoric to certain musical

figures, and we gradually understood

it better, until it was just a matter

of course, an everyday feature of our

playing. The first time round, you're

all excited about the discovery, and

this causes you to exaggerate a

little: We’ve found

something unprecedented! We're not

exaggerating, this is how it's meant

to sound! So it's quite possible that

a later recording of the same work

sounds more natural; that's something

you can only achieve by years of study

and practice.

Benjamin-Gunnar

Cohrs, Bremen

Translation:

Clive

Williams, Hamburg

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|