|

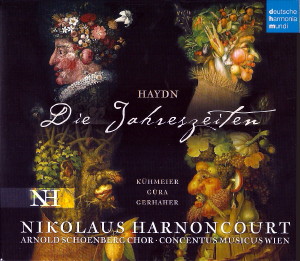

2 CD -

88697 28126 2 - (p) 2008

|

|

Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Die Jahreszeiten, Hob. XXI:3

|

|

|

|

Oratorio for Soloists, Chorus

and Orchestra - Libretto by Baron

Gottfried van Swieten after The

Seasons by James Thomson

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Der

Frühling

|

|

32' 30" |

|

| - Ouvertüre und

Rezitativ "Seht, wie der strenge Winter

flieht" (Simon, Lucas, Hanne) |

6' 06" |

|

CD1-1

|

| - Chor des Landvolks

"Komm, holder Lenz" (Chor)

|

3' 53" |

|

CD1-2

|

| - Rezitativ "Vom Widder

strahlet jetzt" (Simon) |

0' 30" |

|

CD1-3

|

| - Arie "Schon eilet froh

der Ackersmann" (Simon) |

3' 51" |

|

CD1-4

|

| - Rezitativ "Der

Landmann hat sein Werk vollbracht"

(Lukas) |

0' 33" |

|

CD1-5

|

| - Terzett und Chor

(Bittgesang) "Sei uns gnädig" (Hanne,

Lukas, Simon, Chor) |

5' 42" |

|

CD1-6

|

| - Rezitativ "Erhört ist

unser Flehn" (Hanne) |

1' 08" |

|

CD1-7

|

| - Freudenlied (mit

abwechselndem Chor der Jugend) "O wie

lieblich ist der Anblick" (Hanne, Lukas,

Simon) |

10' 47" |

|

CD1-8

|

| Der Sommer |

|

36' 17" |

|

- Einleitung und Rezitativ "Im

grauen Schleier rückt heran" (Lukas,

Simon)

|

3' 26" |

|

CD1-9

|

| - Arie und Rezitativ "Der

munt're Hirt versammelt nun" (Simon,

Hanne) |

3' 16" |

|

CD1-10

|

- Terzett und Chor "Sie steigt

herauf, die Sonne" (Hanne, Lukas, Simon,

Chor)

|

4' 40" |

|

CD1-11

|

| - Rezitativ "Nun regt und bewegt

sich" (Simon, Lukas) |

1' 48" |

|

CD1-12

|

| - Kavatine "Dem Druck erlieget

die Natur" (Lukas) |

3' 38" |

|

CD1-13

|

| - Rezitativ "Wilkommen jetzt, o

dunkler Hain" (Hanne) |

3' 47" |

|

CD1-14

|

| - Arie "Welche Labung für die

Sinne" (Hanne) |

4' 53" |

|

CD1-15

|

| - Rezitativ "O seht! Es steiget

in der schwülen Luft" (Simon, Lukas,

Hanne) |

2' 22" |

|

CD1-16

|

| - Chor "Ach, das Ungewitter

naht" (Chor) |

4' 07" |

|

CD1-17

|

| - Terzett und Chor "Die düst'

ren Wolken trennen sich" (Lukas, Hanne,

Simon) |

4' 20" |

|

CD1-18

|

| Der Herbst |

|

36' 58" |

|

- Einleitung und Rezitativ "Was

durch seine Blüte" (Hanne, Lukas, Simon)

|

2' 20" |

|

CD2-1

|

| - Terzett und Chor "So lohnet

die Natur den Fleisß" (Simon, Hanne,

Lukas) |

6' 39" |

|

CD2-2

|

| - Rezitativ "Seht, wie zum

Haselbusche dor" (Hanne, Lukas, Simon) |

1' 00" |

|

CD2-3

|

- Duett "Ihr Schönen aus der

Stadt" (Lukas, Hanne)

|

8' 29" |

|

CD2-4

|

- Rezitativ "Nun zeiget das

entblößte Feld" (Simon)

|

0' 50" |

|

CD2-5

|

| - Arie "Seht auf die breiten

Wiesen hin" (Simon) |

3' 14" |

|

CD2-6

|

- Rezitativ "Hier treibt ein

dichter Kreis" (Lukas)

|

0' 43" |

|

CD2-7

|

- Chor "Hört, das laute Getöm"

(Landvolk und Jäger)

|

6' 23" |

|

CD2-8

|

- Rezitativ "Am Rebenstocke

blinket jetzt" (Hanne, Lukas, Simon)

|

0' 57" |

|

CD2-9

|

| - Chor "Juchne, der Wein ist da"

(Chor) |

6' 23" |

|

CD2-10

|

Der

Winter

|

|

31' 27" |

|

| - Einleitung und Rezitativ "Nun

senket sich das blasse Jahr" (Simon,

Hanne) |

5' 22" |

|

CD2-11

|

| - Kavatine "Licht und Leben sind

geschwächet" (Hanne) |

2' 02" |

|

CD2-12

|

| - Rezitativ "Gefesselt steht der

breite See" (Lukas) |

1' 24" |

|

CD2-13

|

| - Arie "Her steht der Wandrer

nun" (Lukas) |

3' 47" |

|

CD2-14

|

| - Rezitativ "Sowie er naht,

schallt in sein Ohr" (Lukas, Hanne, Simon) |

1' 07" |

|

CD2-15

|

| - Lied mit Chor "Knurre,

schnurre, knurre" (Chor) |

2' 51" |

|

CD2-16

|

| - Rezitativ "Abgesponnen in der

Flachs" (Lukas) |

0' 21" |

|

CD2-17

|

| - Lied mit Chor "Ein Mädchen,

das auf Ehre hielt" (Hanne, Chor) |

3' 19" |

|

CD2-18

|

| - Rezitativ "Vom dürren Osten

dringt" (Simon) |

0' 38" |

|

CD2-19

|

| - Arie mit Rezotativ "Erblicke

hier, betörter Mensch" (Simon) |

4' 52" |

|

CD2-20

|

| - Terzett und Doppelchor "Dann

bricht der große Morgen an" (Hanne, Lukas,

Simon, Chor) |

6' 14" |

|

CD2-21

|

|

|

|

|

| Genia Kühmeier,

Soprano (Hanne)

|

|

Werner Güra,

Tenor (Lukas)

|

|

| Christian

Gerhaher, Baritone (Simon) |

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master |

|

|

|

Concentus Musicus

Wien

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violin |

-

Eduard Hruza, Double bass |

|

| -

Annette Bik, Violin |

-

Michael Schmid-Castorff, Flute |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violin |

-

Reinhard Czasch, Flute &

Piccolo

|

|

| -

Annelie Gahl, Violin |

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violin |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Silvia Iberer, Violin |

-

Wolfgang Meyer, Clarinet |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel-Vock, Violin |

-

Alvaro Iborra, Clarinet |

|

| -

Ingrid Loacker, Violin |

-

Milan Turkovic, Bassoon |

|

| -

Veronika Kröner, Violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich, Bassoon |

|

| -

Annemarie Ortner, Violin |

-

Christian Beuse, Contrabassoon |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violin |

-

Johannes Hinterholzer, Horn |

|

| -

Florian Schönwiese, Violin |

-

Sandor Endrödy, Horn |

|

| -

Elisabeth Stifter, Violin |

-

Michel Gasciarino, Horn |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi, Violin |

-

Markus Hauser, Horn |

|

| -

Irene Troi, Violin |

-

Andreas Lackner, Trumpet |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, Viola |

-

Herbert Walser, Trumpet |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, Viola |

-

Dietmar Küblböck, Trombone |

|

| -

Herlinde Schaller, Viola |

-

Josef Ritt, Trombone |

|

| -

Dorle Sommer, Viola |

-

Horst Küblböck, Trombone |

|

| -

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

-

Martin Breinschmid, Timpani |

|

| -

Nikolay Gimaletdinov, Violoncello |

-

Ulrike Stadler, Percussion |

|

| -

Dorothea Schönwiese, Violoncello |

-

János Figula, Percussion |

|

| -

Andrew Ackerman, Double bass |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Hammerklavier |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal, Graz (Austria)

- 28 giugno / 2 luglio 2007 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Firedemann Engelbrecht /

Michael Brammann / Tim Schumacher /

Teldex Studio Berlin |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi -

88697 28126 2 - (2 cd) - 69' 15" + 67'

32" - (p) 2008 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

"In The

Creation

the angels speak and tell of God, but

in The Seasons it's only Simon

who talks." With these words Joseph

Haydn is said to have explained to the

Emperor Franz I the

completely different character of his

last oratorio after The Creation.

It was a work very

European in spirit that the

69-year-old composer presented to a

Vienna audience in April 1801: an

English didactic poem from the

Enlightenment era in German

translation, set to music by an

Austrian composer in the spirit of the

French ‘imitation aesthetics’. But the

roots of Haydn’s

wonderful score go back much

farther-back to his childhood in the

country.

AD NOTAM

A SUBJECT CLOSE TO HAYDN’S HEART

In 1727 the master coach-builder

Matthias Haydn put up a low thatched

cottage in the little market town of

Rohrau in Lower Austria. Five years

later his son Franz Joseph

was born there, the child who was to

become one of the greatest of all

composers. When

Beethoven was shown a picture of the

Haydn family home as he lay on his

deathbed in 1827, he cried "A

simple peasant's hut where so great a

man was born!".

Strictly speaking, Haydn didn’t

grow up in a genuinely rustic milieu:

unlike fellow composer Dvořák a century

later, he didn’t have to look after

his father’s cows. But coach-builder

Haydn senior also owned vineyards, fields

and livestock in Rohrau. Thus little

Franz Joseph grew up

in agricultural surroundings, with his

father doubtless telling him the odd

story of his great-grandfather, who

earned his living as a day labourer in

the Burgenland.

These details of Haydn's youth are

important for an understanding of his

last oratorio. A composer born and

raised in a town like Mozart,

whose father was also a composer or

the doctor’s son Handel, could never

have written a work like The

Seasons with such ardour and

persuasive power. The genre pictures

from the life of simple country folk

that illustrate the changing seasons

call for some knowledge of the rural

environment, Haydn was speaking from

the heart and from experience when he

described ploughing and sowing in

springtime or the grape harvest in the

autumn. When he has his farmer Simon

whistle a tune as he

works in the field - the melody is the

famous andante theme from his "Surprise"

symphony -, he undoubtedly had a

concrete image from his own youth in

mind.

Haydn's direct identification with the

text also relates to the oratorio's

moral message, which is about the

happiness of hard-working people. A

simple peasant is rewarded by nature

and Heaven alike for the wonders he

coaxes forth frorn the soil with his

skill and patience. With the Lord’s

blessing, and assisted by the changing

seasons, the country people enjoy the

fruits of their labour. Haydn himself

knew plenty about that: he was fond of

remarking, in reference to his own

humble beginnings, that "young

people can see from my own example

that you can make something out of

nothing", adding that "I admittedly

had talent in me, and thanks to this,

combined with hard work, I gradually

progressed". Even though Haydn

scattered his seed on to manuscript

paper rather than on the soil, he

certainly appreciated the value of

hard work. Otherwise he wouldn't

have been able to write such an ardent

song for his chorus praising the toil

of an inventive person.

There is a third aspect of the

oft-criticized libretto of The

Seasons that probably touched

the old master: the metaphor of the

winter of life that is spread out

before the listener in the fourth and

final section. In

addition to the seasons themselves,

the oratorio also focuses on the

different periods in our life. Man's

life span progresses from the youthful

light-heartedness of

spring through the maturity of summer

and the rich harvest of autumn to the

rigidity of winter, when death is in

the air. And it was precisely at this

transition from the autumn to the

winter of his own life that Haydn

chose to write The Seasons.

THE HAPPINESS OF THE HARD-WORKING MAN

After he completed the work not

without some difficulty - between1799

and 1801 he was struggling with his

“growing weakness“,

he didn’t immediately enjoy

the fruits of his labours. The

premiere on 24th April 1801 in

Vienna’s Palais Schwarzenberg was

certainly a succès

d'estime, with waves of

applause, but the first public

performance a month later in the Großer

Redoutensaal didn't bring the

hoped-for breakthrough, and with only

700 paying guests, the takings were

pretty meagre into the bargain. Only

once the score went into print and

Haydn’s publisher paid him 4,500

florins did he have cause to be

content. The sum was four times the

annual salary that Prince Esterházy

had paid him and ten times as much as

Mozart had received 15

years previously for Le nozze di Figaro.

For the son of a craftsman who always

measured happiness in monetary terms,

this handsome payment was just as

great a triumph as the gradually

growing popularity that the new

oratorio enjoyed through repeat

performances. At the Imperial

court, in the Hofburgtheater, and in

countless concert halls outside

Vienna, The Seasons was given

to resounding applause. Scarcely

anyone had expected the work to step

out of the shadow cast by The

Creation so quickly, not even

Gottfried van Swieten, the librettist

who commissioned the work.

With Mozart’s help, the erstwhile

diplomat and prefect of the imperial

court Library had put

on German versions of Handel oratorios

at the end of the 1780’s

in Vienna. The same aristocratic

society that had arranged the Handel

performances under van Swieten's aegis

now commissioned performances of

Haydn’s late oratorios as well. It was

no coincidence that the scripts came

from England. After Milton's Paradise

Lost had served as the basis of

The Creation, van Swieten chose

the Scottish writer james Thomson’s

didactic poem The Seasons, a

bestseller of the early Enlightenment,

for the new work. From the 4.000

plus verses, van Swieten selected

those scenes that were most

interesting from a musical point of

view, translated them into German and

gave them to Haydn, accompanied by

detailed notes on the how best to set

them to music!

Van Swieten’s ambition

to give the great composer musical

advice was in keeping with his inflated

self-esteem as an author. The Haydn

biographer Griesinger remarked

laconically: "In his

own products he fell victim to all the

errors and shortcomings that he was

wont to criticize in others". His

ideas of tone painting caused him to

fall out with Haydn. The composer

found the librettist’s demands for "all

manner of depictions or imitations

irksome", and would have preferred the

score to be "free of

all this poppycock".

In van Swieten‘s eyes,

however, The Seasons were as

much his work as they were Haydn's,

especially as he planned them to be

the second part of a trilogy that was

to culminate in an oratorio about the

Last Judgment. But

this was not to be: van Swieten died

in 1803, by which time Haydn had given

up composing anyway. Thus the

collaboration between the two unequal

talents remained confined

to the two great oratorios, The

Seasons were regarded

thenceforth not so much as a

continuation of The Creation

as a contrast to their predecessor:

one work was sacred in character, the

other secular; The Creation

was noble and sublime, The Seasons

was more a collection of graphic genre

pictures. Haydn himself apologized to

his biographer Carpani for the later

work with a simple explanation: "In

one work the characters are angels, in

the other they’re peasants". Be that

as it may, the peasants in The

Seasons nonetheless sing the

praises of their Creator in sublime

tones, too. This explains the almost

contradictory diversity of the

oratorio.

IMAGES OF EARTHLY HAPPINESS AND

HEAVENLY BLISS

Hardly any other oratorio in the

history of the genre arouses such a

wide variety of feelings, alternating

in rapid succession and apparently

contradictory, as The Seasons.

In his review of the

première for the Allgemeine

Masikalische Zeitung, the

leading music journal

of its day in Germany, Griesinger gave

an apt description of the effect of

these rapidly alternating scenes and

emotions: "The

work elicited silent reverence,

astonishment and noisy enthusiasm in

the audience one after the other... At

one moment the listener is delighted

by a song tune, the next moment the

peace is shattered as if by a rushing

river that bursts

its banks - all

the instruments come in together to

tremendous effect; one minute, one is

charmed by the simple expression, free

of any artifice, then the next one finds

oneself admiring the lavish lushness

of rapid, bright chords. From

beginning to end the spirit finds

itself helplessly swept along from

deeply touching moments to dreadful

ones, from the utmost naivety to the

utmost artifice, from the beautiful to

the sublime."

When we think of The Seasons

today, the first images that spring to

mind are pictures of earthly

happiness, what Griesinger referred to

as the “naive” element. The old master

introduces his main characters to us

in infectious good humour. First on

the scene is the tenant farmer Simon,

who plods along behind his plough and

improves his mood as he works by

whistling the not entirely unfamiliar

melody mentioned above, which the

orchestra strikes up. Then we meet his

daughter Hanne, who dallies with the

young farmer Lukas as

they stroll through the countryside

together. Lukas is soon her devoted

admirer, and in the middle of the

autumn fruit harvest he sings the

praises ofthe pretty country girls, "their

colour as fresh as the fruit that they

gather": ladies from town can’t hold a

candle to their rural cousins. Simon,

Hanne and Lukas:

three happy souls going about their

everyday work, each of them proud of

his simple rural happiness.

In the choruses, the private happiness

of the father; his daughter and her

husband-to-be is expanded into a

large-scale panorama of rural life. In

the spring the farmers pray to the

Lord for fine weather to help the

seeds grow. In the

summer they extol the sunrise - but

only until the sunlight starts to get

really hot. The sultry heat inevitably

brings a thunderstorm that has man and

beast alike diving for shelter:

everyone scatters until the tolling of

the vespers bell finds them assembled

demurely in their homes again. As

autumn arrives, the peasants let

themselves go and enjoy some

boisterous fun, be it as as helpers to

the aristocratic huntsmen as they

shoot pheasants, hares and deer, or be

it at wine festival, which soon

develops into a hedonistic orgy. And

even winter, a dark, cold and menacing

time, turns out to have its own quiet

appeal: As they sit at their

spinningwheels and sing, Hanne strikes

up a ballad ridiculing the “fine” lord

ofthe manor. The final choruses of

each section are dedicated to the

Creator in all cases: these are hymns

telling of the heavenly bliss that

increases our earthly happiness.

LOVE OF NATURE, OR "FRENCH

RUBBISH"?

In painting these genre scenes in

music, the aged Haydn once again used

the entire palette of his genius, much

to the surprise of his contemporaries.

Where the act of Creation

inspired him to ‘recreate’ in music

all the creatures that began to stir

on land and in the water at the Lord’s

command, he now turned his attention

to the result: to nature in

all its infinite abundance and

variety. Since Vivaldi's Four Seasons

and the Musicalischer Instrumental-Calender

of Haydn’s predecessor as

Kapellmeister to Prince Esterházy,

Gregor Joseph Werner,

such depiction of the passing seasons

was part of the standard skills of any

self-respecting 18th century

composer. And Haydn certainly made

generous use of it in both his string

quartets and his symphonies: there are

examples aplenty in both genres, e.g.

the “Hen” symphony, the “Bird” quartet

or the “Lark” quartet-all nicknames

inspired by onomatopoeic effects in

the score. And nature idylls on the

opera stage tired the composer's

imagination to equal degree, as is

evident from the garden ofthe

sorceress Armida, or the dramatic

powers of transformation that her

colleague Alcina possesses in Orlando

Paladino. In The Seasons,

Haydn had the opportunity to display

this facet of his genius in one last,

grandiose panorama.

The ‘sound effects’ are contributed in

all cases by the orchestra: they make

their first appearance in the prelude

to each of the four sections. Spring

is preceded by a dark picture of

winter storms that are not at all keen

to give way to the "blissful

moon". For although the score tells us

that the introduction "represents

the transition from winter to spring",

after a brief idyllic section with

birdsong, the gloomy G minor sounds of

winter return once more, before they

get bogged down at the end in chords

ofliterally Beethovenian force. Not

until the accompagnato recitative in

the bass does the transition to spring

finally take place and the raw winds

hasten back to their caves "with

a dreadful howling". Here, Haydn

deliberately alternates the sequence

of text and music: at one point the

orchestra illustrates a line or a

single word that has just

been sung, while at another it

anticipates a sentence not yet spoken,

such as the first passage sung by the

soprano. Here a bright spring day finally

dawns, in musical terms

as well, and a few bars after we hear

spring establish itself in the

orchestra, the chorus also sings its

praises in the finest

pastoral tones.

In the other three

seasons, too, the introduction in each

case leads into the first scene in

similar manner, preceding the tableau

of sumrner, autumn and winter

respectively with a characteristic

starting situation. In the second of

the four parts, the introduction

presents "dawn",

the prelude to Autumn portrays

"the farmer's

happiness about the bountiful harvest",

while the prelude to Winter

depicts "the thick fogs

that signal the beginning of winter".

As Haydn's portrayal of

each season progresses, the orchestra

doesn't miss any picturesque details

that flora and fauna, the vagaries of

the weather and the farmer's toil have

to offer. In Spring

we hear a musical picture of the dew

that covers the meadows and the flowers

poking up their heads from the grass.

In Summer we

hear the crickets chirping (C sharp

against D in the high flutes!)

and the frogs croaking. The summer’s

day seems particularly long and rich

in musical images: it begins in the

twilight of a hazy daybreak, and comes

to a first climax in

a splendid sunrise, then reaching its

second climax rn a thunderstorm. At

the end of the day we hear the vespers

bell chiming eight times. In Haydn's

day, the country folk went to bed at 8

pm (admittedly not Central European

summer time!).

In Autumn

we hear a hunting dog prowling

around once it has picked up the

scent of a partridge, increasing

speed until it suddenly stops -

its master has got the prey in his

sights. One shot brings the bird

down: the dead partridge plummets

to the ground. More drastic and

graphic still is the chaos that

breaks out as the frightened hares

run hither and thither with the

dogs hard on their heels, while

the horns kick up a real din as

they play a compendium of the best-known hunting

signals.

The music at the onset of Winter

is dull and gloomy, but before

long these melancholy tones are

dispelled by the above-mentioned

scenes in the cozy parlour.

Every one of these details is

depicted with disarming naivety

and most vividly - there is no

trace of the composer's

irritations overthe things Baron

van Swieten asked him to "stoop to".

Notwithstanding annoyance about

one or two points, Haydn was able

to place his “Soli Deo Cloria“ at

the bottom of a magnificent score.

In this,

his last monumental work for choir

and orchestra, he achieves a

wealth of orchestral texture

beyond that in any of his previous

compositions. As far as

instrumentation and harmony is

concerned, The Seasons

possesses a quality nothing short

of prophetic in the way it points

far into the musical future, into

the Romantic period.

PRAISE BE TO THE LORD!

In the choruses of The Seasons

it is not the country folk alone

that we hear. The composer himself

also speaks to us in the spirit of

a final, emphatic declaration of

faith in his Creator. "Eternal,

almighty, gracious God" is the

line sung on the great key shift

from D to B flat in the closing

chorus of Spring. This is

exclaimed not only by the farmers

in the hope of clement weather to

improve the harvest. Here, "Papa Haydn" is speaking

himself, e.g, in the lines:

"The

table of Thy bounty hast. Thou for us

prepared.

And from Thy mercy's fountain,

our thirsting souls restored!"

The abundance of the Lord's

blessing in nature can be

understood here as a reference to

the Eucharist, where the faithful

partake of the body and blood of

Christ. In

such moments, The Seasons

are no longer a secular oratorio,

but take on a sacred character. At

every remarkable point when a

hitherto unheard-of timbre

suddenly appears, or a modulation

takes the music in an unexpected

direction, Haydn is using his

genius to praise his Creator. It

is "gracious

God” who stands above all else in

this work, and who blesses the

farmers with the harvest in

autumn:

"What

spring, the various blossom’d

put in white promise forth,

What summer suns and

showers

to ripe perfection brought,

rush boundless now to view,

gladdening the husbandman."

Even in his old age, Haydn

once again displayed the full

wealth of his own creative power

in the late autumn of his career.

In every

bar of this last, arduous harvest,

he gives heartfelt

thanks to the Lord.

But it is not only solemnity and

gratitude that hold sway in the

choruses. They could even be described

as subversive in places, although

Haydn wrote a particularly large

number of complex fugues here. One

of these is the song in praise of

hard work in Autumn.

This piece is a busy, 'industrious' fugue such as

one would expect to find in the Cum

Sancto Spiritu section of a

mass. Here, the venerable form

serves to praise a new era and its

spirit: hard work in this case

stands for human ingenuity, full

of enthusiasm and untiring-it is a machine

that Haydn praises here, in all

likelihood the steam engine that was such a

source of fascination at the time.

Another of the oratorio’s fugues

deliberately comes apart at the

seams: for the conclusion of the

wine festival Haydn wrote what he

called "a

drunken fugue". In this number, everyone intentionally

comes in at the wrong moment,

starts on the wrong note or makes

embarassing chromatic

slips. In a drunken stupor, even

the good-natured farmer loses control, while the

members of the chorus need to be

fully alert if they are to perform

all the deliberate

hiccups as naturally as

possible...

In this

respect, each of the big choruses

in The Seasons is a marvel

of inspiration and a challenge for

the interpreters. This applies to

both the genre scenes like the

hunt, the wine

festival or the spinning room and to

the natural spectacles: the sunrise,

the scorching midsummer heat, the

thunderstorm. In this oratorio, the

soloists strike up a new tone as well.

They emerge from the half-courtly,

half-bourgeois concert halls of

Viennese classicism into the fresh air

- literally. In spite

of their entirely urban singing

skills, despite cantabile and

coloratura, each of the three

characters is first and foremost a

simple and honest soul. That’s why

Haydn wrote vocal numbers for Simon,

Hanne and Lukas that don’t belong to

genres familiar from opera and

oratorio. The pieces that Haydn's

three rural folk sing deal with bliss

and abundance, with refreshment and

grace, sometimes as pastoral scenes,

sometimes as simple rustic dancing

songs.

THE WINTER OF LIFE

Right at the end, one last dark shadow

falls across the bright colours of

Haydn's tone

painting. It is

not so much the actual winter that

drives the wanderer down icy paths

before it entices him back to his cozy

fireplace. No, it is rather the

admonishing forefinger that Thomson

raises at the end of his ‘didactic

poem’ to lend the seasons an

allegorical meaning. In

a solemn aria in E flat maior, Simon

sings the decisive words of warning:

"Behold, o fond,

deluded man,

in this thy pictured life behold!

Soon pass thy years of flowering

Spring,

thy Summer's ardent strength

declines.

Thy sober Autumn fades to age,

and pale concluding Winter comes

at last, and shuts the scene.

Where now are fled those dreams of

greatness,

of happiness, those hopes?"

For both

the authors, for Haydn and van Swieten

alike, these verses had a very direct

relevance. Yet Haydn placed them at a

certain distance: he attached more

importance to the triumphant promise

of the final chorus than to the

admonition of the aria: "Then

the great morning dawns". After the

Last Judgment, only

the pious and godfearing will

participate in this 'new

existcnce'. All men will

be redeemed who have led a virtuous

life in keeping with the Sermon on

the Mount and indeed with the

maxims ofthe Enlightenment. Right up

to its very last lines, The

Seasons remains a 'didactic

poem' set to music in the spirit of

the European Enlightenment:

“But who shall dare

to enter in?

The man who does the will of God.

And who shall mount the holy hill?

The pure in heart shall see their

God.

And who may in that temple dwell?

The-merciful shall mercy find.

And who shall gain eternal peace?

Who maketh peace shall peace enioy."

Josef

Beheim, 2008

Translation:

Clive

Williams, Hamburg

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|