|

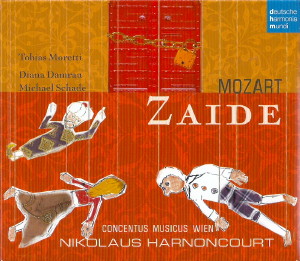

2 CD -

82876 84996 2 - (p) 2006

|

|

Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zaide, KV.

336b/344

|

|

|

|

| Deutsche

Singspiel in zwei Akten - Libretto von

Johann Andreas Schachtner |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ouvertüre

- Sinfonia Es-Dur, KV. 184

|

|

8' 11" |

CD1-1

|

| Erster Akt |

|

46' 56" |

|

|

Einleitung: "Jetz

hören Sie doch auf!" - (Erzähler) |

5' 12" |

|

CD1-2

|

| - Nr. 1 Chor

der vier Sklaven: "Brüder, laßt

uns lustig sein" |

0' 58" |

|

CD1-3

|

| - Nr. 2 Melologo:

"Unerforschliche Fügung!" - (Gomatz) |

6' 46" |

|

CD1-4

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Dieser ohnmächtige, kraftlose, matte

Gomatz" - (Erzähler) |

2' 20" |

|

CD1-5

|

| - Nr. 3 Aria:

"Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben" -

(Zaide) |

7' 15" |

|

CD1-6

|

| - Nr. 4 Aria:

"Rase, Schicksal, wüte immer" - (Gomatz) |

4' 20" |

|

CD1-7

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Zaide hat ihn natürlich heimlich

beobachtet" - (Erzähler) |

0' 51" |

|

CD1-8

|

| - Nr. 5 Duetto:

"Meine Seele hüpft vor Freuden" -

(Zaide, Gomatz) |

2' 35" |

|

CD1-9

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Die beiden haben ein Glück" -

(Erzähler) |

1' 05" |

|

CD1-10

|

| - Nr. 6 Aria:

"Herr und Freund, wie dank' ich dir!" -

(Gomatz) |

3' 43" |

|

CD1-11

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Und in Allazim entbrennt nun auch ein

Kampf" - (Erzähler) |

0' 24" |

|

CD1-12

|

| - Nr. 7 Aria:

"Nur mutig, mein Herze" - (Allazim) |

4' 29" |

|

CD1-13

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Zaide ist jetzt wieder dazugekommen" -

(Erzähler) |

0' 42" |

|

CD1-14

|

| - Nr. 8 Terzetto:

"O selige Wonne" - (Zaide, Gomatz,

Allazim) |

6' 10" |

|

CD1-15

|

| Zweiter Akt |

|

51' 56" |

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Und wie's der Teufel halt so will" -

(Erzähler) |

1' 52" |

|

CD2-1

|

| - Nr. 9 Melologo

ed Aria: "Zaide entflohen!" -

(Soliman) |

7' 58" |

|

CD2-2

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Natürlich ist auch Soliman, wie alle

Reichen" - (Erzähler) |

1' 14" |

|

CD2-3

|

| - Nr. 10 Aria:

"Wer hungrig beu der Tafel sitzt" -

(Osmin) |

3' 43" |

|

CD2-4

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Für Soliman ist der Fall klar" -

(Erzähler) |

0' 52" |

|

CD2-5

|

| - Nr. 11 Aria:

"Ich bin so bös' als gut" - (Soliman) |

5' 43" |

|

CD2-6

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Jetzt wird es eng für Zaide" -

(Erzähler) |

0' 55" |

|

CD2-7

|

| - Nr. 12 Aria:

"Treulos schluchzet Philomele" - (Zaide) |

7' 03" |

|

CD2-8

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Jetzt dreht sich's um: Zaide weint,

schluchzt, klagt" - (Erzähler) |

1' 05" |

|

CD2-9

|

| - Nr. 13 Aria:

"Tiger! wetze nur die Klauen" - (Zaide) |

4' 38" |

|

CD2-10

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Allazim stößt ins gleiche Horn" -

(Erzähler) |

0' 39" |

|

CD2-11

|

| - Nr. 14 Aria:

"Ihr Mächtigen seht ungerührt" -

(Allazim) |

4' 32" |

|

CD2-12

|

|

Zwischentext:

"Das Letzte Quartett!" - (Erzähler) |

1' 11" |

|

CD2-13

|

| - Nr. 15 Quartetto:

"Freundin, stille deine Tränen" -

(Gomatz, Allazim, Soliman, Zaide) |

7' 07" |

|

CD2-14

|

|

Schluss: "Und

hier, am tiefsten Punkt des Konflikts" -

(Erzähler) |

3' 20" |

|

CD2-15

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Diana Damrau,

Soprano (Zaide)

|

|

Michael Schade,

Tenor (Gomatz)

|

|

| Rudolf Schasching,

Tenor (Soliman) |

|

| Florian Boesch,

Baritone

(Allazim) |

|

| Anton Scharinger,

Bass (Osmin) |

|

| Tobias Moretti,

Narrator |

|

|

|

| Concentus Musicus

Wien |

|

-

Erich Hobarth, violin

|

-

Lynn Pascher, viola |

|

-

Alice Harnoncourt, violin

|

-

Dorle Sommer, violone |

|

-

Karl Höffinger, violin

|

-

Herwig Tachezi, violoncello |

|

-

Helmut Mitter, violin

|

-

Dorothea Schönwiese-Guschlbauer,

violoncello |

|

-

Peter Schoberwalter, violin

|

-

Susanne Müller, violoncello |

|

| -

Maria Bader-Kubizek, violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman, violone |

|

| -

Christian Eisenberger, violin |

-

Hermann Eisterer, violone |

|

-

Thomas Fheodoroff, violin

|

-

Robert Wolf, flute |

|

-

Editha Fetz, violin

|

-

Reinhard Czach, flute |

|

-

Annelie Gahl, violin

|

-

Hans Peter Westermann, oboe |

|

| -

Silvia Iberer, violin |

-

Marie Wolf, oboe |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel-Vock, violin |

-

Milan Turkovic, bassoon |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich, bassoon |

|

-

Veronica Kröner, violin

|

-

Eric Kushner, horn |

|

| -

Herlinde Schaller, violin |

-

Alois Schlor, horn |

|

-

Irene Troi, violin

|

-

Andreas Lackner, trumpet |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, viola |

-

Herbert Walser, trumpet |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus, viola |

-

Marti Breinschmid, timpani |

|

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Großer Saal, Musikverein,

Vienna (Austria) - 9-13 marzo 2006 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

Friedemann Engelbrecht /

Michael Brammann / Teldex Studio Berlin

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi -

82876 84996 2 - (2 cd) - 55' 07" +

51' 56" - (p) 2006 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Mozart's first

‘Turkish’ singspiel

Up to now, scholars have

hardly managed

to supply

any satisfactory answers to the

many questions attached to Mozart's singspiel Zaide.

The opera, which Mozart's widow

Constanze found

among her husband’s papers only in 1799, eight

years after

his death, is regarded as a fragment - less in

musical than in dramatic terms,

however, for the work as it has come

down to us lacks the spoken

dialogues, which are indispensable

for an 18th-century singspiel. The

absence of the dialogues written by

the librettist

Johann

Andreas Schachtner makes

reconstruction difficult, as indeed does

the fact that the history of both

the opera Zaide and its

rnaterial is

closely

interwoven with that of the

better-known Entführung

aus dem Serail. Mozart’s

first 'Turkish' singspiel

was composed (1779-80) only shortly before Entführung (1781), and this

and also the fact that both works

have the sarne subject - namly the so-called Turkish opera

- makes it almost

irnpossible

to look at Zaide

impartially.

In contrast

to the richly-documented

history of Die Entführung

aus dem Serail, the

researcher interested in Zaide

finds himself

confronted with a gaping void.

Mozart and his librettist

Schachtner were both in Salzburg

in 1779/80, and there are no surviving

documents from the period when the

opera was presumably composed

(between spring and autumn 1780)

The singspiel does not

crop up in Mozart`s

correspondence until late

1780/early 1781, when he was

working on Idomeneo,

and comes clearly into view in

April 1781 in the run-up to Die

Entführung

aus dem Serail. On 11th

December 1780, Mozart's father

Leopold wrote to his son, who

was in Munich at the time: "I can’t get

anything done about the

Schachtner drama. The theatres

are closed, and the Emperor, who

is only preoccupied with the

theatre has no interest in the

project. It

is actually better that way, as

the music isn't completely finished anyway,

and who knows

what opportunity may present

itself to come to Vienna on this

account?" In

other words, Mozart’s

father is

telling him

that the theatres remain closed

because of the state of national

mourning declared after the death

of Maria

Theresia. Thus there is no

chance of getting the opera

performed at present, and particularly not in

Vienna. So the Mozarts

attempted to launch Wolfgang’s 'Turkish'

singspiel at the newly-founded

Nationaltheater, even though

the theatre had not issued any

concrete commission for such a

piece. At the same time, Mozart

continued to pursue the Vienna

idea, as we learn from a letter

dated 18th April 1781; "As for the

Schachtner operetta, nothing is to come of it

- for the reason I have already

mentioned so often. The young

Stephani is going to give me a

new piece, which he assures me

will he a good one, and if I’ve already

departed hence, he will send

it to me. I

couldn’t disagree with Stephani, I

simply said that the piece is very

good indeed - except for the

lengthy dialogues, which could

easily be altered - but that it is

not suitable for Vienna, where

people prefer comedies." This

passage is informative in the

extreme, first and foremost

because Mozart admits here that

the piece has two serious

shortcomings, namely

the long-winded spoken dialogues

and the earnest subiect-matter.

This meant that the opera was not

in keeping with the taste of

Viennese audiences, and this was

already half a death sentence. The

reason that Mozart says he has "already mentioned

so often" was evidently the

problematic dramatization

with its imbalance between music

and spoken dialogue.

In1936 Alfred Einstein presented

his fellow musicologists with a

libretto that is identical, in

many places, with that of Zaide.

The riddle of Mozart's

singspiel seemed to have been

solved. The libretto concerned had

been published in Bolzano in 1779 under the

title Das Serail, oder Die

unvermuthete

Zusammenkunft in

der Sclaverey zwischen Vater,

Tochter und Sohn. This "musical

singspiel" was set to music by the

Passau Kapellmeister

Joseph

Friebert, while the identity of

the librettist remains unknown to

this day. The most striking

parallel between the two seraglio

operas is without a doubt the fact that most of

the characters have similar or

even the same

names: Zaide,

Comatz (in the

Mozart: Gomatz),

the Sultan (Sultan Soliman), a

renegade (Allazim)

and Osman (Osmin). In the Bolzano

libretto, the events revolve

principally around the Suitan's

relationship to the renegade, who

once

saved the Sullan’s life. The plot

develops accordingly: Zaide and

Comatz recognise the renegade, who

is actually Prince Ruggiero, us

their father, and the Sultan is so

moved that he grants everyone

their freedom. It is pretty

obvious that Mozart

was not exactly enthusiastic about

such a simple ‘family re-union'

from the fact that he changed

Bretzner’s original libretto of Entführung

aus dem Serail, where he

altered precisely this point.

Even if Schachtner’s Zaide

dialogues have been lost, Mozart’s

opera still contains spoken text,

namely in the melodramas. The

presence of melodramas in Mozart’s singspiel

reveals the markedly experimental

character of the work: here,

Mozart was adapting a genre that

was hardly compatible with the

south German form of the singspiel. But thc

melodramas are mainly instructive

in dramatic terms: they tell us

more about the dramatic personae

(Gomatz and Soliman)

than the arias do. In Gomatz's

melodrama (no. 2)

we find ourselves faced with a

character full of sentimentality and pathos,

whose emotional outbursts are

clearly aimed at the foreign

culture with which he is

confronted. Much moreso than

Belmonte in Entführung,

Gomatz is a

xenophobe. The underlying cultural

conflict in Mozart’s opera is

evident in the second melodrama at the

beginning of Act II. Unlike the Bolzano Serail,

Mozart portrays here a Sultan

Soliman who has been cheated and

is now overwhelmed with thirst for

revenge, a character who is likewise not at a

loss for a few juicy racist terms.

The Sultan’s melodrama also

reveals that Mozart and Schachtner

intensified his character strongly

- but only in one direction. Mozart’s Soliman

is a far cry from the enlightened

and liberal-minded Turkish ruler

presented to Viennese audiences

not long after in the person of Bassa Selim in Entführung

aus dem Serail. The Sultan

in Zaide corresponds more to the

picture of the vindictive oriental

despot. In

this way, Mozart and Schachtner

stepped up the conflict to an

extent where it is hard to believe

that this same Sultan suddenly

does a volteface

at the end of the story and grants

the Europeans their freedom. The libretto of

Zaide is indebted to the

traditional image of the Turks purveyed by many an 'Oriental'

drama of the

day. And in view of the fact that

the Austrian dramatist

(and librettist of Entführung) Stephanie junior fell the

opera to be too earnest, we cannot

cornpletely rule out the

possibility that Zaide was originally

rneant to have a tragic ending.

With their modifications of the

‘Turkish libretto’, Schachtner and

Mozart lent the piece clear

drarnatic contours. Mozart may

even have rnade his first appearance

here as a dramatist

- in his previous Italian operas,

there was scarcely

any opportunity for him to influence the

dramatic side of the proceedings.

However, the radical way the composer

and his librettist went about it also had its price

- the opera could not be performed

in Vienna in this Form. But though

this may have restricted the work’s commercial

chances at the time, the emphatic

move towards a German opera seria

is precisely

what makes this daring operatic

experiment from the year 1780

fascinating to the modern

listener.

Thomas

Betzwieser

Translation: Clive

Williams, Hamburg

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|