|

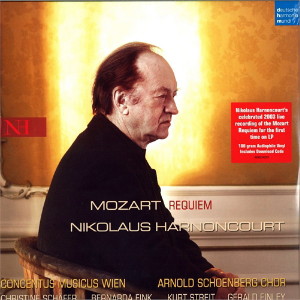

1 CD -

82876 58705 2 - (p) 2004

|

|

| 2 LP -

88985342001 - (c) 2016 |

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Requiem d-moll, KV 626 |

|

|

|

| Completed by Franz Xaver

Süssmayr (1766-1803) - [New, Revised

Edition by Franz Beyer] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I. Introitus: Requiem (Chor,

Sopran) |

|

4' 57" |

1

|

| II.

Kyrie (Chor) |

|

2' 56" |

2

|

| III. Sequenz: |

|

19' 41" |

|

| - Dies irae (Chor) |

1' 50" |

|

3

|

| - Tuba mirum (Sopran, Alt,

Tenor, Bass) |

3' 52" |

|

4

|

| - Rex tremendae(Chor) |

1' 58" |

|

5

|

- Recordare(Sopran, Alt,

Tenor, Bass)

|

6' 19" |

|

6

|

| - Confutatis (Chor) |

2' 35" |

|

7

|

| - Lacrimosa(Chor) |

3' 07" |

|

8

|

| IV.

Offertoriun: |

|

6' 52" |

|

- Domine Jesu (Chor, Sopran,

Alt, Tenor, Bass)

|

3' 50" |

|

9

|

- Hostias (Chor)

|

3' 02" |

|

10

|

| V. Sanctus (Chor) |

|

1' 19" |

11

|

VI. Benedictus (Chor, Sopran, Alt,

Tenor, Bass)

|

|

5' 20" |

12

|

VII. Agnus Dei (chor)

|

|

3' 25" |

13

|

VIII. Communio: Lux

aeterna (Chor, Sopran)

|

|

5' 45" |

14

|

|

|

|

|

| Christine Schäfer,

Soprano |

|

| Bernarda Fink,

Alto |

|

| Kurt

Streit,

Tenor |

|

| Gerald Finley,

Bass |

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg Chor

/ Erwin Ortner,

Chorus Master |

|

| Concentus

Musicus Wien |

|

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Großer

Musikvereinssaal, Vienna (Austria) - 27

novembre / 1 dicembre 2003 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann / Josef

Schütz (ORF)

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi - 82876 58705 2 - (1 cd)

- 50' 15" - (p) 2004 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

| Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi - 88985342001 - (2 lp) -

24' 27" + 25' 48" - (c) 2016 - DIG |

Note

|

| Il

CD contiene una traccia CD-Rom

contenente copia del manoscritto

originale del Requiem. |

|

| Mozart and his

Requiem: A musician's

reflections and Feelings |

It

is undeniably tempting to speculate what

course Mozart’s music would have taken

if he hadn’t died such a tragically

early death. A 70-year-old Mozart would

have been a vigorous contemporary of

Beethoven and Schubert, of\Weber and the

young Mendelssohn. One can well imagine

that these composers might have written

different music if they had had Mozart

looking over their shoulder, as it were.

Not only musical history, but probably

world history, too, would have evolved

differently: Mozart would probably have

been the musical focus ofthe Congress of

Vienna, instead of Beethoven...

The great works that Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart penned in the last months of his

life point the way - the Clarinet

concerto, Zauberflöte, La

clemenza di Tito and the Requiem:

the tonal language becomes more

succinct, the melodies more ‘catchy’,

the harmonies and the overall sound more

‘Romantic’. A significant contribution

in this respect is made by the

clarinets, whose soft tone, capable as

it is of modulation, blends with the

sounds of the horns and the strings much

better than the customary oboes. In the

19th century, clarinets were actually

used in many symphonies in place of the

oboes called for in the score, in order

to create this 'Romantic' sound. In the

Requiem, Mozart specifies bassett horns

in F - a newly-developed type of

clarinet whose veiled, dark sound is

heard in the opening bars, and which

Mozart returns to time and again as a

source of peace and comfort after the

outbursts of the choir, of the trumpets

and trombones. (These are just my own

impressions I am describing here, I'm

not attempting a musicological

analysis.)

The appearance of the great G minor

Symphony expressed clearly what had

already been hinted at before - in the

chamber music, in the death quartet in Idomeneo:

a glance into the dark recesses of the

soul that was ‘unheard of' in the music

of Mozart's day. This new tonal language

was felt to be so shocking that the

Swiss composer and publisher Hans Georg

Nägeli (1773-1836) wondered whether one

should even expose the public to it!

This Symphony in the ‘death key' of G

minor had a decisive influence on my own

career: time after time in my days as an

orchestral musician, I was forced to

play it in such harmless and sugary

interpretations that in the end I

couldn’t bear this misunderstanding of

Mozart’s music any longer: I had no

choice but to leave the orchestra and

take up the baton myself!

Mozart’s Requiem had an overwvhelming

effect from the outset - on concert

audiences, of course, but also on

generations of composers. Even

Beethoven, who was himself nothing if

not a radical musical spirit, found it

“too wild and terrible”. He was going to

write one himself, but more

“conciliatory” in manner. Today, we are

suprised at such reactions, for we

hardly expect to find such devastation

and terror even in Mozart’s most

shattering works (there is a parallel

here to the reception of the G minor

Symphony). The best part of a century

later, Bruckner still regarded the

Requiem as a model and an unattainable

masterpiece that he quoted time after

time in his symphonies - e.g., the

harmonic sequence of four bars with

which the autograph score of the Lacrimosa

ends on the words "qua resurget ex

favilla judicandus homo reus", or the

opening motif of the Introitus

in the woodwind and in the chorus

“Requiem aeternam”. This unbroken

effect, indeed popularity, over a period

of more than 200 years is something i

can’t explain, and it affects me too on

an entirely personal level.

I had already played the Requiem in the

orchestra when I was but a child, and

was deeply moved. Why? Many listeners

have the same experience; this is

haunting music, a work that literally

‘gets under your skin’, no matter what

objections the musicologists and Mozart

experts may voice about the fragmentary

character of the piece or about

Süßmayr's inadequate completion ofthe

score. Most ofthe additional music

undoubtedly has its roots in Mozart -

Süßmayr must have had sketches or other

information at his disposal, otherwise

real Mozartian thematic and harmonic

crossreferences would not have been

possible, these would have been beyond

Süßmayr's abilities. (To give a couple

of examples of what I mean: the bass in

the Agnus Dei is an enlargement

of the Requiem theme; the interval steps

of the Hosanna correspond to

those of the Recordare; and the

melody of the Sanctus

corresponds to that ofthe Dies Irae.)

Süßmayer's mistakes have been corrected

as far as possible in Franz Beyer’s

edition, but Beyer deliberately

refrained from adding any newly-composed

music. Thus we have to go without the Amen

fugue (at the end of the Lacrimosa)

as the conclusion of the Dies Irae

sequence.

There’s one more thing I’d like to point

out. In nearly all other cases, Mozart’s

music is conspicuously independent of

his biography. The great composer wrote

sad or light-hearted works irrespective

of his own state of mind; this much is

convincingly conveyed in Hildesheimer’s

book on Mozart. But the Requiem seems to

be the exception that proves the rule:

in the truly terrifying Dies Irae

sequence, for example, the composer’s

fortunes are reflected so movingly in

the music that the personal relevance

cannot be missed (e.g. Recordare:

"statuens in parte dextra"; Confutatis:

“gere curam mei finis"). Anyone who

listens to this marvellous work cannot

help but feel this identification, and

that may well be the ultimate reason for

the incredible effect that the Mozart

Requiem has.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, 2004

Translation:

Clive

Williams

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|