|

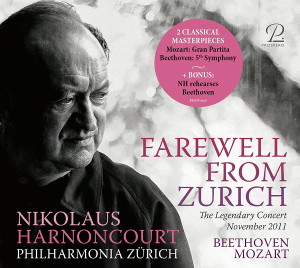

2 CD -

PROSP 0020 - (p) 2011 & (c) 2021

|

|

| Farewell from Zurich -

The Legendary Concert November 2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

(1756-1791) |

|

|

|

| Serenade Nr. 10 für Bläser

B-dur, K. 361 (370a) "Gran Partita" |

|

52' 49" |

|

| - Largo - Molto Allegro |

10' 59" |

|

CD1-1 |

- Menuetto

|

9' 48" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Adagio |

5' 00" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - Menuetto. Allegretto |

4' 44" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Romance. Adagio |

7' 52" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - Tema con variazioni.

Andante |

10' 22" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - Finale. Molto Allegro |

3' 58" |

|

CD1-7 |

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van Beethoven

(1770-1827) |

|

|

|

| Symphonie

Nr. 5 c-Moll, Op. 67 |

|

36' 28" |

|

| - Allegro con brio |

7' 06" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Andante con moto |

9' 51" |

|

CD2-2 |

- Allegro

|

7' 36" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Allegro |

11' 44" |

|

CD2-4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bonus:

Nikolaus Harnoncourt rehearses Beethoven,

Symphony No. 5, 2nd & 3rd movement |

|

10' 48" |

CD2-5 |

|

|

|

|

| PHILHARMONIA

ZÜRICH |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Tonhalle,

Zürich (Svizzera) - 25-27 novembre 2011

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live

recordings |

Produced

& engineered / Executive

producers

|

| Andreas

Werner / Roland Wächter (SRF), Martin

Korn (Prospero) |

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Prospero

- PROSP 0020 - LC 91909 - (2 cd) - 52'

49" + 47' 16" - (p) 2011 & (c) 2021

- DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

Nota

|

A

coproduction with SRF 2 Kultur.

(p) 2011 Schweizer Radio SRF 2 Kultur

(c) Martin Korn Music Production

|

|

|

FAREWELL FROM ZURICH - The

Legendary Concert November 2011

|

NIKOLAUS

HARNONCOURT AND THE ZURICH

OPERA HOUSE

He was a loyal

person, the great master Nikolaus

Harnoncourt. Zurich was at the

centre of his great operatic

triumphs. For many decades,

following a strictly regulated

schedule, he used to return to his

artists in Zurich. In November

2011, there was to be a farewell

performance, for once a great

concert at the Tonhalle.

Harnoncourt asked for Beethovens Fifth

combined with Mozart. The serenade

Gran Partita for 13 solo

instruments was chosen. The wet

and cold late autumn season

prompted Nikolaus Harnoncourt to

ask for an unusual rehearsal

setting. The 13 musicians and

myselfwere supposed to travel to

St. Georgen in Upper Austria to

prepare the Gran Partita

at his archaic-looking home (a

former vicarage). A feast lor our

musicians. So we went to the

charming little village, were

accommodated in a small hotel and

enjoyed our extensive work in the

private rooms of the Harnoncourt

family. An unforgettable highlight

for all the musicians involved, an

experience, which has its deeply

rooted place in their biographies.

For me, too, an unforgettable

moment amidst the numerous

encounters with Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, first in my life as a

musician, then as the orchestra

director of the Philharmonia

Zürich.

Heiner Madl

Zurich, in

November 2020

WHAT HE

REALLY MEANT TO SAY

Beethoven's Fifth with

Harnoncourt

When the piece came to an end -

and of course it ends

spectacularly -, there was ai

startled silence. First, people

had to catch breath before

breaking into applause and quickly

getting onto their feet for a

standing ovation. This was not

surprising since nobody in the

hall had probably ever heard

Beetlhven's Fifth like

this: with as much fury in its

tone and as extraordinarily

poignant in its interpretive

design. Nor was it ever perceived

as drastic in terrns of conveying

a very definite meaning. An

earthquake had shaken listeners

through marrow and bones, But not

only that. On this night a life

dedicated to art was reaching its

fulfilment.

Many years before, Nikolaus

Harnoiicourt, a cellist working

with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra

and Herbert von Karajan, had

embarked on his journey as someone

who rediscovered period

instruments and an appropriate way

of playing them. Together with his

wife, violinist Alice Harnoneouri,

and the Concentus Musicus Wien,

founded in 1958, he began to write

a new chapter in the field of

historically informed performance

and eventually brought about a

decisive change in attitude

towards early music. He did,

however, point out relentlessly

that he was noi interested in

reconstruction. His aim was to

retrieve a particular repertoire

from the fossilization it had

undergone through busily and

monotonously repetitive

performances. Bach's St

Matthew Passion and the Brandenburg

Concertos were presented in

a breathtaking new light. At the

same time, he did not have to wait

long for resistence from the music

business.

Harnoncourt was never deterred.

Having become a full-time

conductor and invited by the

leading orchestras of our time, he

extended the scope of his

repertoire, embraced the Viennese

classics and eventually some late

romantic masters. His performances

of Mozart, Beethoven and Bruckner

showed unfamiliar and inspiring

features. Here too, he followed

the principles of ancient music

and its origins, departing from

the fundamental belief that music

is a language, that it also

contains stressed and unstressed

syllables punctuation and breath

marks, variations in tempo, and no

less importantly that it is imbued

with categories and figures of

speech from the art of rhetoric.

And that by logical consequance

music imparts messages, at times

implicity, at other times in a

concrete way. By following this

creed Nikolaus Harnoncourt

challenged current stipulations

established before and

particularly after the Second

World War concerning the

continuous underlying pulse and

the even suond, which is sustained

by a permanent legato and vibrato.

Moreover, he rejected the idea

that music consisted exclusively

of form without content, or, as

Eduard Hanslick had put it, that

"the essence of music is sound and

motion".

When in 1990/91 Nikolaus

Harnoncourt presented Beethoven's

complete symphonies with the

Chamber Orchestra of Europe in

Graz this approach was vividly

palpable. At the same time, one

could not deny that his

performance still contained traces

of a conventional approach. In his

typical way, Harnoncourt of course

took the musical notation at its

word. In the third movement of the

Fifth Symphony - the scherzo with

its twirling fugue in the

corresponding trio -, he restored

the repeat, which Beethoven had

originally written but

half-heartedly cut after the

symphony’s failure at its world

premiere in Vienna in 1808.

Beethoven’s metronome marks,

however, were seen pragmatically

and therefore taken into account

in an approximative way. And the

notion of a continuous underlying

pulse remained imperative

throughout.

During the next two decades of his

work on Beethoven, Harnoncourt

managed to free himself from the

constraints of convention. How

radically he achieved this can be

heard in the live recording of

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 with

the Orchestra of Zurich Opera

(today Philharmonia Zurich) in the

Large Hall of Zurich’s Tonhalle on

26th November 2011. The sound is

generally eruptive, even edgy but

it is also clear and highly

differentiated. It is an approach

which uncovers structures while

putting them into an interpretive

context by assigning them content

and meaning. When in the closing

movement of the Fifth three

trombones join in with the piccolo

and contrabassoon for the first

time in the history of symphonic

music, Harnoncourt brings them out

far more clearly than the

trumpets, who usually overpower

the rest of the orchestra in this

section. This effect is clearly

intended. Trombones are firmly

associated with French

revolutionary music and as

Beethoven's sketchbooks show, his

Fifth Symphony in C minor is

closely related to the Third in E

flat major, which was originally

dedicated to Napoleon before being

renamed the Eroica.

Next to the strikingly keen sound

quality the 2011 performance of

Beethoven’s Fifth from Zurich is

most notable for its hard-driven

tempi. However, the conductor

needs to be held less accountable

for this than the composer and his

metronome markings, which were

published from 1817 onwards and

for a long time considered

impossible to execute. In contrast

to the earlier recording,

Harnoncourt takes them at face

value this time. Notwithstanding

that, the basic tempi turn out to

be of little relevance since he

unvariably modifies and adapts

them with great suppleness to

match the expressive momentum of

each situation. This is most

apparent in the quavers opening

the fugue in the middle section of

the third movement: unusually

drawn out at first, they break

into an enormously tearing

pace within a single bar.

Such effects are not the liberties

musicians might have taken at the

close of the 19th century. In

those days performers considered

themselves next-level composers

whose rendition was determined by

a deeply subjective response to

what they found in a score.

Harnoncourt’s extreme handling of

tempo changes, on the contrary, is

based on recent insights of the

period practice movement, which

brought to light that the idea of

a continuous tempo derives from

the aestheticism of New

Objectivity, a German movement

established in the early 20th

century. Moreover, like all

elements in Harnoncourt’s approach

the choice of tempo is founded on

the conductor’s conviction that

Beethoven’s Fifth contains a kind

of programme. According to his

belief, this symphony is not about

Fate knocking three times at our

door and our eventually overcoming

it during the course of the four

movements. He sees the symphony as

a tale of oppression (in the

opening movement), of suffering

and hope (in the Andante con

moto), of defiance (in the

scherzo) and triumphant liberation

(in the finale). One might agree

or disagree with such an explicit

interpretation but it is very hard

to resist the intoxicating sweep

of Harnoncourt's musical rendition

of these ideas.

In the Zurich performance of

Beethoven’s Fifth, he seemed to be

in complete harmony with himself,

sharing without restraint what he

meant to say as a musician who had

undergone a transformation from an

early music pioneer into an

expressionist artist par

excellence. All this came to

light during a highly symbolic

concert: it was dedicated to the

memory of Claus Helmut Drese, the

recently deceased former general

manager of Zurich Opera, who had

from 1975 onwards invited

Harnoncourt to produce the

legendary Monteverdi-cycle at this

theatre. At the same time, it

marked the conductor’s farewell

after a thirty-six year-long,

exceptionally fruitful presence in

this city. The special atmosphere

of the occasion had already been

evident in the "Gran Partita",

played in the first half of this

concert. Mozart's work too was

governed by the conductor’s highly

individual expressivity.

Nevertheless, his interpretation

contained moments of wonderfully

relaxed beauty, above all in the

sublime Adagio. Because Nikolaus

Harnoncourt was like this too.

Peter Hagmann

Translation:

Markus Wyler

THANK YOU...

I am overjoyed

that, after almost 10 years,

Nikolaus Harnoncourt's Zurich

farewell concert -

that extraordinary performance

from late November of 2011 - has finally

made its way to friends of

music and those who honour the

artistry of this

exceptional musician. My

thanks go first of all to the

former Director of Zurich Opera,

Alexander Pereira, with whom I

had already discussed

publishing a recording around the

time of the concert and who

had the wonderful idea of

recording the rehearsals as

well. I am deeply indebted to

Heiner Madl, Qrchestra

Director of the

Philharmonia Zürich, too, for

his unstinting support, his

beautiful photographs of rehearsals

and for his perceptive

introductory remarks. I wish

to express my thanks to the

many musicians of the

Philharmonia Zürich, who

constantly encouraged me to

publish this musical document.

I am also grateful to Etienne

Bujard, Roland Wächter

and Andreas Müller-Crépon of

Swiss Radio SRF, and to

Andreas Werner for his

careful musical preparation

and creation of the audio

master. Thank you et

merci beaucoup to Marcel

Chollet, Markus Wyler and

Brigitte and Tom Zilocchi

for your support with the

translations. I am

particularly indebted to Dr Peter

Hagmann, who wrote the

wonderful booklet text and

continuously spurred me on

over the years and encouraged

me not to relent in my efforts

to make this

magical concert available to

audiences.

And

finally my heartfelt thanks go

to the Harnoncourt family

above all to Alice Harnoncourt,

who from the very start

supported having this Zurich

farewell concert

published. As many know, Alice

had what can only be described

as a symbiotic bond with her

husband and was not only his

constant companion in his

career from the earliest

years until its conclusion,

but also left her indelible

mark on it as well: as an able

adviser regarding performance

practice questions, as

orchestra leader, and as a constant and

strong presence in the

background who tirelessly

assisted him in all matters with

poise and grace. I was

delighted beyond measure with

her spontaneous willingness to

cooperate, her agreeing to

have the recording published,

and her support in

transcribing her husband's

rehearsal instructions. It is

my hope that listeners

today will also be able to

sense the special atmosphere,

the gratitude and unbounded

excitement of the auditorium

at the Zurich Tonhalle on

those days before Advent

in 2011.

Martin

Korn

Zollikerberg,

Switzerland, spring 2021

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|