|

|

12

dischi a 78 rpm - (p) 1953

|

|

| 1 CD -

CD 379 - (c) 2004 |

|

| 2 CD -

SU 4213-2 - (p) 1953 (c) 2016 |

|

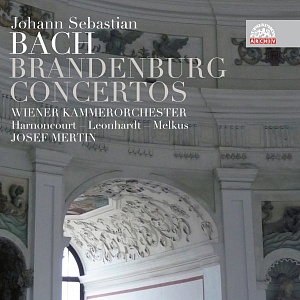

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BRANDENBURG

CONCERTOS, BWV 1046-1051

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Concerto

No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 |

|

23' 28" |

|

| - (without tempo indication) |

4' 30" |

|

CD1-1

|

- Adagio

|

3' 46" |

|

CD1-2

|

| - Allegro |

5' 09" |

|

CD1-3

|

- Menuetto - Trio I - Polacca

- Trio II

|

9' 54" |

|

|

| Concerto

No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 |

|

12' 03" |

|

| - (without tempo indication) |

5' 16" |

|

CD1-4

|

| - Andante |

3' 41" |

|

CD1-5

|

| - Allegro assai |

3' 00" |

|

CD1-6

|

| Concerto No. 3 in G major,

BWV 1048 |

|

12' 46" |

|

| - (without tempo indication) |

6' 40" |

|

CD1-7

|

- Allegro

|

6' 07" |

|

CD1-8

|

| Concerto No. 4 in G major,

BWV 1049 |

|

19' 02" |

|

| - Allegro |

8' 05" |

|

CD2-1

|

| - Andante |

4' 40" |

|

CD2-2

|

| - Presto |

6' 08" |

|

CD2-3

|

| Concerto No. 5 in D

major, BWV 1050 |

|

22' 43" |

|

| - Allegro |

11' 09" |

|

CD2-4

|

| - Affettuoso |

5' 21" |

|

CD2-5

|

| - Allegro |

6' 03" |

|

CD2-6

|

| Concerto No. 6 in B flat

major, BWV 1051 |

|

17' 19" |

|

| - (without tempo indication) |

6' 36" |

|

CD2-7

|

| - Adagio, ma non tanto |

4' 33" |

|

CD2-8

|

| - Allegro |

6' 02" |

|

CD2-9

|

|

|

|

|

Members of the

WIENER KAMMERORCHESTER and guests

|

|

-

Edith Steinbauer, violin, leader,

viola (2nd viola in No.6)

|

-

Elisabeth Schaeftlein, recorder

|

|

| -

Alfred Altenburger, violin |

-

JŁrg Schaeftlein, recorder, oboe

|

|

| -

Alice Hoffelner (Harnoncourt),

violin |

-

Camillo Wanausek, flute

|

|

-

Eduard Melkus, viola (1st viola

in No.6)

|

-

Helmut Wobisch, trumpet

|

|

| -

Nikolaus Harnoncourt,

violoncello, viola da gamba? |

-

Bruno Seidlhofer, harpsichord

(solo in No.5) |

|

-

Frida (Krause) Litschauer,

violoncello

|

-

and others

|

|

-

Gustav Leonhardt, viola da gamba

|

|

|

|

|

| Josef Mertin,

conductor |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Casino Baumgarten, Linzer

Strasse, Vienna (Austria) - 1950 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

Bernhard Trebuch / Karl

Wolleitner (ORF) - Matouö Vlčinskż /

Karl Wolleitner (Supraphon)

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

- ORF

"Alte Musik" - CD 379 - (1 cd) -

48' 43" - (p) & (c) 2004 - AAD

mono (BWV 1048, 1049 e 1051)

- Supraphon -

SU 4213-2 - (2 cd) - 48' 41" + 59' 27" -

(p) 1953 (c) 2016 - AAD mono (BWV

1046-1051)

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

| Supraphon - 23291/23302 - (12

dischi, 24 facciate, 78 rpm) - durata

48' 43" + 59' 22" - (p) 1953 - mono |

|

Nota

|

The FIRST recording with

period instruments.

Special thanks to Alice Harnoncourt,

Ingomar Rainer and Robert

Wolf for the information on the

recording and the members of the

ensemble.

|

|

Notes (CD

Supraphon

SU 4213-2)

|

On

Josef Mertin's

recordings of the

Brandenburg

Concertos

When, in

1950, post-war Europe,

whose political and

cultural scene had

been mercilessly

divided by the Iron

Curtain, was

commemorating the

200th anniversary of

the death of Johann

Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750), the

festivities were borne

in the spirit of

numerous symbolic

connotations. They

were aimed at

re-embracing the most

valuable assets of

conflict-debased

German art, as well as

celebrating Bachís

universally

comprehensible musical

language. The

festivities were

particularly vigorous

in war-ravaged,

divided Germany and

neighbouring Austria,

whose music centres of

Salzburg and Vienna

saw the Bach

anniversary as am

opportunity to hold

numerous commemorative

events and concerts.

The Bach jubilee was

not overlooked by the

Czechoslovak music

publisher Supraphon,

which duly implemented

a project that would

have no parallel in

the country in the

years to follow.

Making the best of the

composerís

anniversary, the

company utilised the

repertoire in the

record catalogue, the

post-war availability

of fledgling Viennese

artists and its

contacts with the

musical circles in the

Austrian capital. In

the 1950s. Supraphon

produced a host of

remarkable recordings,

primarily featuring

core Czech

19th- and 20th-century

music, with many of

them catching the

attention of critics

and discerning

listeners abroad. From

the late 1950s,

Supraphonís success

was increased in part

owing to the

engagement of renowned

foreign conductors and

instrumentalists,

including those

hailing from beyond

the Eastern bloc (John

Barbirolli, Jean Fournet,

Antonio Pedrotti, and

others). Nevertheless,

at the time, none of

the state publisherís

projects

came into being

outside the country,

and without the

participation of

Czechoslovak artists,

as had been the case

of the recording of

Bachís Brandenburg

Concertos, BWV 1046-1051

(1718-1721), made in

Vienna in 1950.

The

history of the album

started in the heart

of the Broumov

Promontory in the

northeast of Bohemia

by the Czech-Polish

(until 1945,

Czech-German) border.

In

March 1904, Josef

Mertin (b.

21.3.1904 Broumov, d.

16.2.1998 Vienna) was

born into a German

family living next to

the Benedictine

Monastery. Following

his graduation from

the local grammar

school, where he had

received thorough

training in singing,

the violin, piano and

organ, and a brief

spell as a music

teacher in his remote

native town

(1922-1925), in 1925

he received a

scholarship from the

company Benedikt

Schrollís Sohn and

moved to Vienna in

order to study voice

and sacred music at

the Wiener

Musikakademie. While

in the Austrian

capital, in 1927 and

1928 he formed a

chamber orchestra and

passed exams in church

music and pedagogy,

and in 1928 he

graduated as

Kapellmeister from the

Neues Wiener

Konservatorium. Mertin

concurrently attended

musicology seminars at

the Universitšt

Wien. In

1928, at the age of

24, he made his debut

with the Wiener

Kammerorchestervereinigung;

from 1932 he conducted

Hans GŠlís

Madrigalchor

(1890-1987);

and in 1933 he founded

his own instrumental

ensemble, Collegium

musicum Wiener

Musikakademie.

At the

end ofthe 1920s and

the beginning of the

1930s, in addition to

new contemporary music

and Bach pieces (the Saint

Matthew Passion,

on period

instruments), Mertin

also performed

compositions by

Guillaume de Machaut

(c. 1300-1377), whose

moderntiine premieres

in Vienna caused quite

a stir, as well as by

his beloved Heinrich

SchŁtz.

He taught at the

Kapellmeisterschule

and the Neues Wiener

Konservatorium

(1928-1938), the

Wiener Volskhochschule

(1932-1938), and at

the Musikakademie

(1937-1938). In

1950 he left the

Konservatorium der

Stadt Wien so as to

continue teaching at

the Musikakademie

(1946-1978) and organ

restoring (from 1931

he worked at the

Federal Monuments

Office), to carry out

research into the

building of historical

musical instruments

and put together a

collection of early

instruments at the

Kunsthistorisches

Museum in Vienna.

Evidently the most

intriguing of his

activities were

Mertinís experimental

early music

performances at the

Hofburgkapelle and the

Albertina gallery

(from 1934, he held

his own concert series

at the Festsaal der

Graphischen Sammlung

der Albertina). His

achievements in the

domains of music,

education,

organisation.

restoration and

collecting earned him

the title of

Professor, the Cross

of Honour for Science

and Art (1960), the

Gold Medal of Merit

for the University of

Music and Performing

Arts in Vienna (1989),

and the Silver Medal

of Merit of the

Republic of Austria

(1994).

Before

Josef Mertin died at

the age of 93, he

could not only look

back fondly at his

long life filled with

music and pioneering

work focused on its

early stylistic

periods, he was also

able to observe with

pride the progress of

his numerous pupils

(Claudio Abbado,

Mariss Jansons, Zubin

Mehta, and others),

many of whom had been

enticed by his

unconventional

teaching methods and

imbued with a

passionate ardour for

early music. The New

Testamentís "For

many are called, but

few are chosen"

(Matthew 22:14) also

applied to Mertinís

students, the majority

of whom could only put

up with his not overly

systematic educational

methods for a few

lessons. Yet those who

did remain faithful to

Mertinís apostolic

verve and rccondite

pedagogic techniques

embraced performance

of early music on

period instruments and

copies in the post-war

decades so fiercely

that they almost

condemned their

teacher's

name to becoming a

mere encyclopaedia

entry. The most gifted

of Mertinís pupils in

the late 1940s

included the Austrian

violinist Eduard

Melkus (b.

1.9.1928 in Baden an

Wien), who in 1946

assumed the post of

concert master of

Mertinís Collegium

musicum and served his

teacher as a faithful

and practical guide

through the

vieissitudes of the

music scene in Vienna

(from 1951 to 1953, he

studied in Switzerland

with the Vienna-born

violinist of Czech

origin Petr RybŠř,

a friend of Bohuslav

Martinů).

Melkus also followed

in Mertinís footsteps

by founding early-music

ensembles, Schola

antiqua Wien (1952)

and Capella academica

Wien (1965), and

finally, as a

professor of the

violin, viola, Baroque

violin and

historically informed

early-music

performance at the

Universitšt

fŁr

Musik und darstellende

Kunst Wien

(1958-1996).

When in

the autumn of 1950,

following years spent

at the Schola

cantoruin basiliensis

in Basel (1947-1950),

the gifted Dutch

organist and

harpsichordist Gustav

Leonhardt (1928-2012)

arrived in Vienna to

study musicology, he

immediately joined

Mertinís early-music

seminar attended by a

number of antagonistic

talents. Mertinís

students also included

the gifted recorder

player Elisabeth-Liesel

Schaeftlein

(1927-1993), a Graz

native and sister of JŁrg

Schaeftlein

(1929-1986), the

legendary oboist of

Concentus musicus Wien

(1953). Probably in

1948, she introduced

to Mertin

and his disciple

Melkus her gangly

compatriot Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

(1929-2016), who from

1948 studied the cello

with Emanuel Brabec at

the Musikakademie. Had

Elisabeth-Liesel

Schaeftlein not done

so, the young Harnoncourt

would most likely have

pursued the path of a

solo instrumentalist,

or ďjustĒ a player of

the Wiener

Philharmoniker,

performing DvořŠkís

and Straussís music,

instead of becoming

one of the major

figures of

historically informed

early music

performance of the

second half of the

20th century. Had it

not been for

Elisabeth-Liesel

Schaeftlein, in 1950

Mertinís student team,

extended for the sake

of the imminent

recording of the Brandenburg

Concertos with a

group of players of

the Kammerorchester

of the Wiener

Konzerthausgesellschaft,

who for its time and

in comparison with

other Viennese

orchestras had an

unusually high

proportion of female

members, would have

had to do without the

cellist Harnoncourt.

The

talented recorder

student

Elisabeth-Liesel

Schaeftlein, the

rising violin star

Eduard Melkus, the

hitherto unknown

cellist Nikolaus

Harnoncourt and the

subtle Gustav

Leonhardt, in the

company of members of

the Wiener

Kammerorchester (l

946), got together in

the studio to make

under the guidance of

Melkus a

groundbreaking album

of the Brandenburg

Concertos. The

project had been

preceded by the

complete recordings

made by Alfred Cortot

(1932, Orchestre de

líEcole Normale de

Musique) and Adolf

Busch (1936, Adolf

Busch Chamber

Players), as well as

accounts of individual

pieces, including, for

instance, Wilhelm Furtwšnglerís

live recordings of Brandenburg

Concertos

Nos. 3 and 5 with

the Wiener

Philharrnoniker at the

Salzburger Festspiele

in 1950. Yet, some two

centuries after Bachís

death, Josef Mertin

decided to take a revolutionary

step and perform the

flagship work

- a "showcase

of the composer's

instrumental

mastery" (N.

Harnoncourt)

- in a chamber

formation, making

use of the

instruments and

applying the

performance canon of

Bachís own time. "within the

Baroque concerto

genre, the concertos

represent an

ultimate apex;

with regard to the

instrumentation,

they are true

chamber music,

unveiling their

value in the more

intimate milieu in

which they were

formerly performed

too. Your

gramophone

recording (with

its most natural

use being for

personal listening

in a private

circle) thus

complies with the

essential trait of this

music," Mertin

wrote to Supraphon

after listening to

the recordings that

were being

completed.

A number of the

period instmments

employed in Mertin`s

recording of the Brandenburg

Concertos were

from his own

collection, which

was also made use of

by the members of

the Wiener

Gamben-Quartett

(1949): Melkus,

Harnoncourt, Alfred

Altenburger

(1927-2015) and Alice

Hoffelner (b.

26.9.1930),

who would marry

Harnoncourt

in 1953. Instruments

from the collection

were also used by

Gustav Leonhardt,

who in Mertinís

recording of the Brandenburg

Concertos

played the viola da

gamba (Brandenburg

Concerto No. 6 in

B flat major).

By the way, the

collection and an

organ built by Mertin

himself (organo di

legno) were

indispensable in the

making of the

generally

better-known 1954

radio recording by

Paul Hindemith of

Claudio Monteverdiís

opera L'Orfeo,

performed by Melkus

and the oldest

generation of the

then not yet named

historical

instruments ensemble

Concentus musicus

Wien, helmed by

Harnoncourt.

In

addition to the

minimalist

configuration, made

up of students of

Mertinís early music

performance class

and the members of

die Wiener

Kammerorchester,

headed by the

concert master Edith

Steinbauer

(1901-1996) and the

cellist Frieda

Litschauer-Krause

(1903-1992), the

wife of the

orchestraís founder,

another natural

facet of the

pioneering 1950

recording was the

adherence to the

original

instrumental

structure of Bach`s

Kothen orchestra,

including two

recorders in the

fourth concerto,

which up until the

1970s

were commonly

replaced with

traverse flutes.

Specific information

about the

instruments played

in the individual Brandenburg

Concertos has

not been preserved,

nor has the date on

which the album was

made. Yet Mertinís

studio recording is

more than a mere

sonic document of a

revolutionary moment

in the history of

performing early

music on modern and

period instruments.

Compared to the

later projects of

Viennese provenience -

Jascha Horensteinís,

implemented in

September 1954,

using historical

instruments

(performed by

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

and members of

Concentus musicus

Wien), and the 1957

recording of Felix

Prohaska conducting

the members of the

Kammerorehester der

Wiener Staatsoper -

Mertinís account

stands out owing to

his endeavour for

the utmost sonic

transparency and

precise leading of

the instrument

parts. Mertin also

gave great thought

to the tempos. Even

though Horenstein

opted for markedly

faster tempos. Mertinís

account is

strikingly akin to

the first of the

series of

Harnoncourtís

recordings of the Brandenburg

Concertos

(1964, 1981/1983,

1982). Mertinís

dismissive attitude

to the romanticising

conception of Bachís

orchestral concertos

is boldly audible in

comparison with

Furtwšnglerís

1950 album: Whereas

Furtwšngler

himself played the

piano on Brandenburg

Concerto No. 5 in

D major

(29:23), Mertin

invited to perform

on the harpsichord

the technically

superlative Bruno

Seidlhofer

(1905-1982) (22:38).

Furtwšngler

turned Bachís

work into a Classicist-Romantic

piano concerto,

while Mertin

returned to the

dialogical character

of the Baroque

concerto.

"]osef Mertin was

the father of all

the endeavours to

purge Romantic and

Baroque music of

romantic deposits

and comfortable

tradition,"

the conductor Milan

Turković,

bassoonist of

Concentus musicus

Wien, wrote years

later. And bearing

cogent witness to

this is even the

oldest of Mertinís

(precious few

preserved) studio

recordings,

surprisingly made by

the Czechoslovak

label Supraphon. For

the first time since

its lirst release,

on 12 shellac discs,

in 1953, Mertinís

complete account (to

whose final

recording the

(self-) critical

Mertin took

exception and,

following the

recordingís

completion, he even

offered to make for

Supraphon new

recordings, this

time only with

Collegium musicum)

is now being

presented to

listeners on CD (in

2004, the year

marking the

centenary of Josef Mertinís

birth and the 75th

birthday of Nikolaus

Harnoncourt,

Austriaís ORF radio

station

released a selection

of the Brandenburg

Concertos Nos. 3,

4 and 6).

Thus, after an

interval of 66

years, music lovers

are offered Mertinís

historically first

recording of the Brandenburg

Concertos in

their entirety, as

performed by his

ensemble on modern

and period

instruments. The

project serves to

pay tribute to

Mertin's

visionary approach

and express

admiration for his

followers, headed by

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt. The

present unique album

is also a proud

reminder of their

Czech connections.

Martin

Jemelka

Translation:

Hilda Hearne

----------

Major birthdays are often very

welcome affairs. In this case,

they provide a suitable occasion

to celebrate two anniversaries,

Josef Mertin's 1ooth and

Nikolaus Harnoncourt 75th, whose

first gramophone recording

appears on the present edition.

Of course I realise theat Josef

Mertin (one of the most modest

peole I have known) would not

have considered this a real

reason to re-issue an historic

recording, least of all one of

his own.

Maybe his description of the

circumstances of this 1950

recording as a "scating over

thin ice" is somewhat

exaggerated, yet it does

represent a memorable step in

the early music revival.

It was prompted by a search for

musical authenticity in the 1950

Bach year.

Matters that seem self-evident

to us today, such as the use of

recorders in the 4th concerto

(until the 1970's the use of

flutes was still customary), the

two viola da ganbas in the 6th

or the chamber.music scoring of

Bach's "Six Concerts Avec

plusieurs Instruments"

were real pioneer events in

1950.

The appearance of Eduard Melkus

and of Gustav Leonhardt, who

taught harpsichord in the 50's

at the Vienna Music Academy, as

gambist in the 6th concerto only

add to the artistic value of the

production.

As with the restoration of

historic instruments, greatest

care was taken with the

production of this re-issue. The

goal was not to reproduce the

original sound (almost

impossible anyway) but, in

favour of a wider sound

spectrum, to document the

condition of the original

shellac discs in 2004. Sound

filters were threfore used only

seldom and then extremely

sparingly, and it was decided

not to put movements together

(akthough this would have been

quite possible) which had been

split up due to the limited

playing time of the discs.

I hope that this recording from

a time far.removed from ours may

not only remind us that musical

interpretations should always be

heard and judged in the context

of their times, but far more

serve to commemorate a

full-blooded musician who, until

late in life, tirelessly trained

and influenced several

generations of students

(including myself), a "homo

faber" archetype who

contributedvsignificantly to the

burgeoning of early music, a

warm-hearted, caring, modest and

very humane person, Josef

Mertin!

Althofen,

December 6th, 2004

Bernhard

Trebuch

|

| Notes (CD

ORF

379) |

This edition consists of

a transfer onto CD of 12 shellac 78 rpm

discs made by Supraphon in Prague

containing three of six Brandenburg

concertos by Johann Sebastian Bach. The

label on the discs attributes the

recording to "Members of the Chamber

Orchestra of Vienna" conducted by Josef

Mertin and recorded in 1950. A

few explanations, amendments and

corrections are required concerning both

the time and circumstances of the

recording and also those taking part.

The early music and authentic sound

movement in Austria in the twentieth

century is closely bound up with the

name of Josef Mertin (1904-1998) who,

until the sixties and seventies, was

considered one of its most important

instigators and mentors. Born in Braunau

in Bohemia (now part of the Czech

Republic), Mertin arrived in Vienna in

the twenties to study music. He

completed his studies within a very

short period (1925-28) with diplomas in

church music, voice and conducting from

the then State Academy and the so-called

New Conservatory. In addition, he

attended lectures on musicology given by

Guido Adler and Rudolf von Ficker at the

university. His experience of Ficker's

combination of scholarship and musical

practice, togheter with the knowledge

and skill he soon acquired in

instrument-making, did much to mark

Mertin's later work as musician, teacher

and maker.

Numerous concerts and church music

activities during the thirties in the

field of youth music-making and organ

playing (with the associated rediscovery

pf pre-Bach music which saw the

beginning of Mertin's lifelong

dedication to Heinrich SchŁtz) were

interspersed with the first occasional

attempts to use historic instruments.

This was to be continued after the war

at the Collegium musicum of the Vienna

Music Academy, where Mertin confronted

an international body og

highly-qualified students with questions

concernin the interpretation of early

music, inspiring them to their own

exploration, as he liked to call it,

which was to spread his exemplary

impetus throughout the world.

These recordings date from this period

shortly after the war. An (unfortunately

undated) copy of a letter

(Mertin-Archiv, Universitšt fŁr Musik

und darstellende Kunst in Wien) from the

professor to the "management of the

Supraphon Record Company, Prague"

provides valuable documentation about

the circumstances as well as Mertin's

own particular views of the recording, a

"personal statement and assessment of

the recentlz-completed recording of

BachŖs Brandenburg concertos".

Mertin assumes that the necessarily "different

nature", even "apparent lack of

uniformity" in the sound

world of each pieces is inherent to

their differing instrumentation and

design (he discusses only concertos III,

IV and VI which he apparently received

as test pressings) and thus found the

very different sounds of the individual

recordings acceptable. However there

were other serious problems, also

concerning the editing and other

technical aspects of the recording,

about which Mertin did notwithhold his

criticism: "The test tape... sounded

much more faithful than the finisched

disc. In my opinion some important

elements in the sound have disappeared

in the cutting (Frequency range

relationships and balance altered)."

The producer was Mertin's friend and

colleague Karl Wolleitner (1919-2004)

working, according to our research, in

the so-called "Casino Baumgarten" on the

Linzer Strasse in Vienna's Penzing

district. The processing of the material

however took place entirely at the

Prague factory. The criticism continue

in concrete detail: "The 3rd concerto

has the most satisfactory 'sound',

since the performers all belong to a

group used to playing together and the

concerto iteself presents the least

problems in terms of sound. As a

recording it is a technical success,

since the composition's design can be

clearly heard. The concerto has only

one dynamic distorsion... the violins

are unreasonably favoured by their

closer position to the microphone. The

record is good."

"Recorders are added to the strings

in the 4th concerto. These are real

historic instruments, and on top of

that, in the hands of wind players

with particular stylistic experience.

This puts the quasi-modern string

sound at a disadvantage, lending it an

unflatteringly penetrating quality."

However, all in all the recording is "well-worth

listening to, and of a

higher quality than other records of

this piece up till now."

Matters start to worsen with the

assessment of the final concerto,

apparently recorded in winter (February

1950?): "The recording [of

Concerto VI Ed.] suffered from the

heasting failure and contains more

faulty notes than acceptable even

under the circumstances." (sic!)

In this context, Mertin addresses a

foundamental problem and handicap to the

whole production: "The Wiener Kammerorchester'

was booked for the recording... this

orchestra is not an ensemble

specialised in early music, although

highly-regarded in Vienna and working

with care and devotion. The orchestra

semply plays in the same standard and

exemplary way as the Philharmonic etc.

are used to playing. But they are not

early music 'specialiss', and as a

result certain stulistic wishes cannot

be fulfilled with this ensemble. The

6th concerto suffers particularly in

this respect... with these players...

a new recording would probably not

produce significantly better results."

A possible alternative was offered: "With

my Collegium musicusm as the Vienna

State Academy (where the recorders

come from!) I have built up an

ensemble that plays on actual historic

instruments." String instruments

restored to their original form are

meant here, subsequently referred to as

"short-necked violins", which

proved more suitable to the demands,

since "a whole host of problems which

otherwise hinder the performance of

early music disappear with the use of

instruments in their original state."

This stylistic approach of the whole

performance is very reminiscent today of

Paul Hindemithžs surviving recordings of

his own works such as the Concerto for

Orchestra op.38 and similar pieces fron

the same period. Mertin's Bach

interpretations also owe something to

the neo-baroque and new objectivity in

the result of his effort to cleanse and

de-romanticise Bach, to reveal the

compositional steucture. Indeed

Hindemith and Mertin worked closely

together on the 1954 Vienna performance

of Monteverdi's "Orfeo" which so

impressed the young Harnoncourt and for

which Mertin provided a specially-made

"organo di legno".

Meanwhile, the stimulos and occasions to

become involved with so-called period

instruments in Vienna came most of all

from Othmar Steinbauer (1895-1962),

himself a violin student of Sevcik who,

rejecting the excessive,

highly-individual romantic string sound

as understood by the Hauer circle,

preferred "old" instruments (even

including the pseudo-Middle Age vielle

newly-designed from iconographic models

but with modern tuning in fifrhs). The

Vienna Gamba Quartet also made its mark

in this field of activity during the

1950 Bach year with a sensational

arrangement of the Art of Fugue

(including a completion of the closing

fugue by Eduard Melkus which remains

exemplary today). Its four members,

Alfred Altenburger, Alice Hoffelner,

Eduard Melkus and Nikolaus Harnoncourt,

who were all closey associated with

Mertin's Collegium, played on adapted

viola d'amore instruments tuned in

fifths, with the bass gamba being the

only instrument we would consider

historic today.

All this led to the suggestion in a

letter for a re-recording of the sixth

concerto with "new soloist: 1a viola:

my best pupil at the Academy with an

original Quinton, 2nd viola: Prof.

Steimbauer on an original old Viennese

master viola; both instruments played

with historic viol bows! 1st gamba, ny

best Academy gamba-player on an

original instrument using historic

bowing style. 2nd gamba: ditto:

also an outstanding pupil."

Further names included the cellist

Frieda Krause-Litschauer, Bruno

Seidlhofer on the harpsichord and an

unnamed double-bass player from the

Philharmonic, also with an original

instrument. Mertin requested that the

additional recording sessions be

organised quickly: "The students with

whom I could make this

stylistically faithful recording have

already graduated and are only

available until May."

He mentions that one has got a job in a

"top-rank Swiss orchestra...

one gentleman is going

back to France, another to Holland".

This sets definite time limits as well

as giving some indications about the

partecipants in the recording. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt was among them, wherther on

the gamba as mentioned above or wherther

on the cello instead of Frieda

Litschauer is no longer certain, as was

Gustav Leonhardt, an excellent

gamba-player in addition to being a

performer on historic keyboard

instruments. He had made his Vienna

debut in 1950 as harpsichordist and

taught at the Music academy from 1952

before taking up his position at the

Amsterdam conservatory in 1954. No doubt

he was the gentleman referred to in

Mertinžs letter who must return to

Holland. In the same year Eduard Melkus

("my best pupil at the Academy"

almost certainly refers to "the

baroquest violinist" according to

Hindemith's famous dictum) took up a

solo viola position in the Zurich

Tonhalle orchestra, the "top-rank

Swiss orchestra" mentioned above.

Thus the earliest recording date for the

6th concerto was to be in the spring of

1954, and it includes the "youthful

work" of a few players who were

later to become some of the best

performers on the scene!

We may now reconstruct the definitive

list of those taking part as follows:

Edith Steinbauer (1901-1996), leader as

well as soloist in no. 4 and second

viola in no.6. Eduard Melkus, viola,

also as soloist in no. 6. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt possibly as cellist in no.

6, but perhaps on one of the gambas.

(That Harnoncourt and very probably also

his future wife, Alice Hoffelner, were

members of the orchestra can also be

confirmed by the listing of the complete

recording as quasi opus 1 in his

official discography.) The stylistically

expert recorder players in the 4th

concerto were brother and sister JŁrg

(1929-1986) and Elisabeth (1930-1993)

Schaeftlein, the former soon to become a

long-serving member and leading light of

Concentus Musicus Wien as baroque

oboist. It goes without saying that the

recorders they used also had nothing in

common with authentic instruments in the

strictest sense. Finally, Bruno

Seidlhofer (1905-1982), later a renowned

piano teacher, is listed as playing

harpsicord continuo.

"The ensemble mentioned here

would also have been better for the

remaining 5th concerto..."

During conversations in later years

Mertin candidly described a recording of

the 5th Brandenburg (with Bruno

Seidlhofer as soloist), clearly made at

the same time, as "entirely unusuable";

it never gor beyond the test pressing,

which is also why we have chosen to

ignore it in the context of this

re-issue. Apparently Hindemith attempted

to direct a recording of the second

concerto with the same team (with Helmut

Wonisch playing trumpet alongside

Elisabeth Schaeftlein on the recorder).

A recording of the first concerto never

seems to have been attempted.

In an introductory text to a production

of all six concertos (and thus not

directly for this edition) containing

much other useful information Josef

Mertin also expresses an interesting

thought about his own, carefully

considered relationship to the recording

medium: "The concertos represent an

absolute pinnacle of achievement in

the genre of the baroque concerto;

their instrumentation in like

true chamber music, whose value is

best revealed in intimate surroundings

such as those in which they were forst

performed. Hnece their appearance on

record (assuming the most natural use

of the record for personal purposes in

intimate surroundings) corresponds to

an important characteristic of

this music."

May this commemorative re-issue of his

production of the Brandenburg concertos

be granted a suitable affectionate

treatment "for personal purposes in

intimate surroundings"!

Ingomar Rainer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|