|

1 CD -

LC 13781 - (p) 2006

|

|

| DIE EDITION - Berliner

Philharmoniker - Im that der Zeit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750) |

|

|

|

Suite (Ouverture) Nr. 1 in C

major, BWV 1066

|

|

25' 13" |

|

| - Ouvertüre: Grave - Vivace

- Grave |

6' 22" |

|

1

|

| - Courante |

2' 47" |

|

2

|

| - Gavotte I und II |

3' 37" |

|

3

|

| - Forlane |

1' 13" |

|

4

|

| - Menuett I und II |

4' 11" |

|

5

|

| - Bourrée I und II |

2' 39" |

|

6

|

| - Passepied I und II |

4' 24" |

|

7

|

Applause

|

|

0' 24" |

8

|

| Concerto for Oboe,

Violin and Strings in D minor (Reconstruction after

Concerto BWV 1060) |

|

13' 44" |

|

- Allegro

|

4' 58" |

|

9

|

- Adagio

|

5' 14" |

|

10

|

| - Allegro |

3' 32" |

|

11

|

| Applause |

|

0' 25" |

12

|

| Suite (Ouverture) Nr. 3 in D

major, BWV 1068 |

|

23' 45" |

|

| - Ouvertüre (ohne

Bezeichnung) - Vite |

11' 03" |

|

13

|

| - Air |

5' 01" |

|

14

|

| - Gavotte I und II |

4' 02" |

|

15

|

- Bourrée

|

1' 10" |

|

16

|

| - Gigue |

2' 29" |

|

17

|

| Applause |

|

0' 21" |

18

|

|

|

|

|

| Albrecht

Mayer, Oboe |

|

| Thomas

Zehetmair, Violin |

|

|

|

| Berliner

Philharmoniker |

|

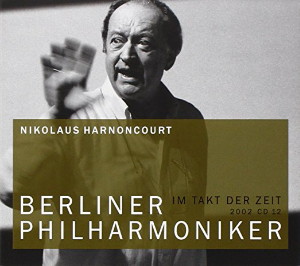

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Philharmonie,

Berlin - 5 ottobre 2002

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wilhelm

Schlemm / Ekkehard Stoffregen (Rundfunk

Berlin-Brandenburg)

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| RBB

Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg - LC 13781 -

(1 cd) - 64' 02" - (p) 2006 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Historian

and Revolutionary - Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

Herbert

von Karajan would never have dreamt

of it - he knew, by the way, exactly

how to prevent such a thing from

happening, both in Salzburg and

Berlin: an insubordinate cellist

from the Wiener Symphoniker

proclaiming a revolution in sound on

gut strings, who yet, in all

seriousness, is valued and esteemed

today by both the Berliner and

Wiener Philharmoniker as one of the

most important authorities on

conducting. A "berserker" who gives

his all and lets his hair down on

the podium, yet is also a

cool-headed scholar, curious,

diligent and precise; one who symply

has to know, who has to go back to

the sources. With a name that sounds

as though it might have come from a

poetry album by the eccentric

Austrian writer

Herzmanovsky-Orlando: Johann

Nicolaus de la Fontaine und

d'Harnoncourt-Unverzagt. An Austrian

born in Berlin on 6 December 1929,

who has lived in Graz, Vienna and

Zurich, the product of a wondrous

mélange of Lorraine and Luxembourg

"ancienne noblesse" and the house of

Habsburg. It has often been asserted

that the 20th century was the era of

the all-powerful conductor, lord of

melody and big money, culminating in

personalities as contrasted as the

brooding Furtwängler,

the choleric Toscanini, the aesthete

Karajan and the entertainer Bernstein.

Yet these were all re-creative

artists, who served the music and

strove to infuse their performances

with life. Even Nikolaus Harnoncourt

would not say anything different about

himself. But this would be a gross

understatement. A cellist who for

years stoically earned his daily bread

in the Wiener Symphoniker and only

came late to conducting, he really did

get something moving, indeed helping

to instigate a revolution from which

the chronically ailing industry as a

whole has profited: the re-evaluation

of pre-Classical music. A public that

had grown tired of the Romantics and

was unsettled by inaccessible

contemporary works now recognized this

repertoire as a treasure offering the

same sort of delighl in novelty that

previous generations had found in the

latest developments of their own time.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt cannot help this

situation, but he has profited from

it. It has made him into a reigning

luminary and one of the conductors who

produce the most, and most important,

recordings. In the process, he has

always managed to ensure that the

composer clearly takes precedence over

the cult of alleged podium

lion-tamers. Harnoncourt, the

anti-star, ranks among the most

influential conductors of the second

half of the 20th century.

Recalling the modest, spare-time

beginnings of Concentus Musicus and

its principals playing on rustled-up

old instruments in Vienna at the end

of the 1950s, this may seem almost

unimaginable. What started out as a

labour of protest in a small niche has

grown into an all-engulfing wave. But

now that the trend for gut strings,

archival truffle hunts, vibrato-less

string playing and exaggerated dynamic

swells has reached its apogee, the

movement's figurehead has already long

since moved on: to Offenbach and

Strauß, Schubert and Schumann, Verdi

and Bruckner, even Wagner.

Since the advent of Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, we hear Mozart and Haydn

differently; we get excited about

Monteverdi, understand Handel, and

have learned to love Bach deeply. No

less gladly, we have been following

the conductor for years now into the

dens of the supposedly conservative

orchestral lions in Berlin, Vienna and

Amsterdam.

It was Claudio Abbado who smoothed

Harnoncourt’s way to the Berliner

Philharrnoniker. In autumn 1991 he

arrived with a symphonic Mozart

programme - that was also an Amadeus

anniversary year. While Abbado’s

domain tended more to opera and

masses, Harnoncourt revealed to the

orchestra wholly unsuspected worlds of

sound. They rehearsed a great deal,

both parties eagerly, and this initial

encounter developed into a long and

fruitful working relationship,

culminating every year when

Harnoncourt returns to the Berliners,

usually for several appearances. And

not necessarily with Classical works:

his Bach concertos (like the one

recorded here) are always an

enlightened, adventurous pleasure that

leaves curiosity satished. Harnoncourt

attends to his love of the Romantics

with performances of Mendelssohn and

Schumann, conducts a Brahms cycle, and

takes special care over Schulnert:

during the course of several seasons

presenting a complete symphony cycle,

selected masses, even a concert

performance of the opera Alfonso und

Estrella.

A number of CDs bear witness to these

Berlin digressions - thpugh for the

intellectual universalist Harnoncourt

they have long since ceased to warrant

that label. One of the first, a

sampling of Strauß waltzes and polkas

with the Berliners, also served as a

delicious foretaste of his ascent of

the Classical (media) Mount Olympus,

the rostrum of the Wiener

Philharrnoniker for its New Year's

Concert. And in March 2000, the

Berliner Philharmoniker had already

honoured him with its highest

distinction, the Hans von Bülow Medal.

Manuel Brug

Translation:

Richard

Evidon

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|