|

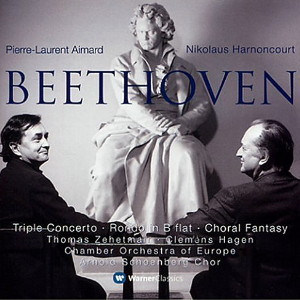

1 CD -

2564 60602-2 - (p) 2004

|

|

| Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Triple Concerto in C major

for violin, cello, piano and orchestra,

Op. 56 |

|

36' 17" |

|

- I. Allegro

|

18' 23" |

|

1

|

| - II. Largo

- |

4' 38" |

|

2

|

| - III. Rondo

alla Polacca |

13' 16" |

|

3

|

|

|

|

|

Rondo in

B flat major for piano and orchestra,

WoO 6

|

8' 25" |

8' 25" |

4

|

|

|

|

|

| Fantasia

in C minor for piano, chorus and

orchestra, Op. 80 |

|

19' 24" |

|

| - I. Adagio

|

3' 33"

|

|

5

|

- II. Finale

(Allegro - ... - Presto)

|

15' 51" |

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas Zehetmair,

Violin (Op. 56)

|

|

| Clemens Hagen,

Cello (Op. 56) |

|

| Pierre Laurent

Aimard, Piano |

|

|

|

| Luba Orgonasova,

Soprano I (Op. 80) |

|

| Maria Haid, Soprano

II (Op. 80) |

|

| Elisabeth von

Magnus, Alto (Op. 80) |

|

| Deon van der Walt,

Tenor I (Op. 80) |

|

| Robert Fontane,

Tenor II (Op. 80) |

|

| Florian Boesch,

Baritone I (Op. 80) |

|

| Ricardo Luna,

Baritone II (Op. 80) |

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master |

|

| Chamber Orchestra

of Europe |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal,

Graz (Austria) - 22-27 giugno 2003 (Op. 80

& WoO 6), 17-22 giugno 2004 (Op. 56) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Warner

Classics - 2564 60602-2 - (1 cd) - 64'

23" - (p) 2004 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

The sinfonia

concertante was a favourite form in

the late eighteenth century,

especially in France. Haydn and, more

famously, Mozart both contributed to

this tradition of multiple concertos.

One of its late offshoots is the

"Konzertant für Violin, Violoncelle

und Pianoforte mit dem ganzen

Orchester" (Beethoven's title) written

in the first months of 1804 for the

composet’s young piano pupil Archduke

Rudolph and two string players in the

Archduke’s entourage - the violinist

Seidler and the cellist Anton Kraft,

for whom Haydn had composed his D

major cello concerto two decades

earlier. As Beethoven stressed to his

publishers Breitkopf und Härtel, the

combination of piano trio and

orchestra was a novel one, but the

novelty failed to catch on. The

Viennese public premiere (following a

performance in Leipzig) in May 1808

was indifferently received because,

according to Beethoven's factotum

Anton Schindler, the (unnamed)

soloists failed to take the concerto

seriously enough, and there is no

record that it was performed again in

Beethoven’s lifetime,

The piano of 1804 was a very different

instrument to the one we know today:

the question of balance that modern

performers must confront - that the

keyboard may overshadow the deep-toned

cello - would not have been an issue

in Beethoven's time. (Pierre-Laurent

Aimard's lightness of touch reserves

this in the present recording.) The

piano writing is light and limpid

throughout, and the cello takes the

star role - Kraft was, after all, a

renowned virtuoso. In each of the

three movements it takes the lead; and

by writing consistently for its

plangent top string, Beethoven enables

it to compete on equal terms with the

violin.

The orchestral introduction tn the

tirst movement sets out the pregnant,

mysteriotts npr-uint; tltctnc.

When the soloists enter (first cello,

then violin, and finally piano - the

usual pattern throughout the concerto)

they immediately set to work,

expanding and enriching the theme with

touches of imitation and chromatic

inflexions in the harmony. Later in an

exposition that combines maximum

terseness with maximum spaciousness,

Beethoven establishes A (major and

minor) rather than the expected

dominant, G major, as the main

secondary key. Here the swinging

marchlike second subject acquires new

shades of meaning through the

brightness of the new key and the

sweet, penetrating timbre of the two

string soloists in their highest

register. Beethoven builds an air of

hushed, tense expectancy with a series

of pianissimo scales and trills and

then brings in the orchestra fortissimo

in a surprise key (F rather than A

major) - a dramatic ploy the composer

was to exploit again two years later

in his Violin Concerto.

The development is initially relaxed,

slipping back to A major as the

soloists each put their slant on the

opening theme. But the music gradually

grows more animated in a modulating

dialogue for piano and strings against

a four-note fragment of the main theme

in the woodwind. There is a lull as

the cello introduces the movement’s

most haunting idea, a plaintive cantabile

in C minor. Then, after another

protracted passage of anticipation,

the recapitulation brings back the

once-mysterious main theme in a

triumphant fortissimo - a

favourite device of Bcethoven’s in his

“heroic” middle period.

The slow movement’s remote key of A

flat had been hinted at in the opening

Allegro, even making a sudden dramatic

appearance in the fortissimo

outburst near the end. For mellow

beauty of colouring few Beethoven

movements surpass this rapt,

meditative Largo, in which thc wind

complement is reduced to clarinets,

bassoons and horns and the orchestral

violins are muted until near the end.

The sonority of the cello playing

softly at the top of its compass, so

characteristic of the concerto, is

magically exploited iu the noble

opening solo and in the theme’s

ornamented repetition for the two

strings against harplike arpeggios

from the piano.

As in the Violin Concerto and the last

two piano conccrtos, the Largo does

not so much end as dissolve into the

Rondo, after a passage in which the

soloists muse ever e long-held G major

chord. The finale is a polonaise (a

very fashionable form during the first

half of the century), whose jaunty

opening theme is immediately countered

by a poetic modulation to E major. In

this particulary interesting and

beautiful example of the form, the

typical “heel-stamp” rhythm, later

fully developed, is initially hidden

in the slurs that phrase the theme.

And while several ofthe other ideas

have a simplicity ideal for

elaboration by the solo trio, there

are two vividly characterised new

themes in the A minor central episode.

In the first of these, introduced for

once by the violin, the dash and

swagger of the polonaise are specially

pronounced. As in the first movement,

Beethoven dispenses with a cadenza.

Instead he reinterprets the main theme

as a boisterous duple-time moto

perpetuo. But just as we seem to

be sighting the home straight, yet

another hushed series of trills leads

to the return of the original

polonaise rhythm and an almost

exaggeratedly formal leave-taking.

Beethoven’s famous benefit concert in

the Viennese Theater an der Wien on 22

December l808 was surely the greatest

showcase of new works in musical

history. In near-freezing conditions,

connoisseurs and amateurs (“Kenner und

Liebhaber“) heard the first public

performances of the Fifth and Sixth

Symphonies, three movements from the C

major Mass, the concert aria Ah,

perfido! and the premiere of the

Fourth Piano Concerto, with the

composer playing the solo part. As if

this weren`t enough, Beethoven decided

at the last minute to compose a

brilliant and stirring finale to the

evening, drawing together chorus,

orchestra and himself as soloist. The

upshot was the hastily written Choral

Fantasy, a unique hybrid in

Beethoven’s output which re-enacts the

Fifth Symphony’s progression from C

minor to C major and heralds in more

naive vein the mighty finale of the

Ninth Symphony. The concluding poem in

praise of universal harmony and the

triumph of light over darkness (echoes

here of The Magic Flute) is

probably the work of Christoph

Kuffner, though Beethoven may have had

a hand in it himself. As usual with

the composer, the copyists’ ink was

barely dry on the day of the concert.

And with inadequate rehearsal time,

the performance of the Fantasia was

apparently chaotic, even falling apart

at one point when Beethoven made a

repeat that the players hadn't

bargained for.

Like its scoring, the Fantasy’s form

is unique. First comes a rhapsodic

introduction for solo piano in C

minor. In the 1808 premiere Beethoven

improvised a different solo here,

writing down this quasi-extemporised

introduction when he prepared the work

for publication the following year.

After a climax of torrential bravura,

the orchestra enters tentatively with

a stealthy little march, answered

quizzically by the keyboard. Then,

with almost comical incongrnity, the

piano announces a melody of childlike

simplicity drawn from a song, Gegenliebe,

that Beethoven had composed in 1794.

As if in celebration of the powers of

music, Beethoven varies the theme by

exhibiting the different instruments

in turn - flute, oboes, clarinets and

bassoons, string quartet (in a

dancing, gossamer texture) and finally

the full orchestra.

The scale is now enlarged with three

variations that expand and deconstruct

the nursery tune. First comes a

section in C minor, initially in

ferociously pounding “Hungarian” style

but later developing the theme in

remote, shimmering modulations (shades

here of the Fourth Piano Concerto).

Beethoven follows this with a

ravishing slow variation in A major

(with the soft, Mozartian colouring of

clarinets and bassoons) and a brash Alla

marcia in F major that prcogures

the tenor solo in the Ninth Symphony’s

Ode to Joy. After another

passage of poetic reverie and a

cadenza-like flourish hom the piano,

the conspiratorial little march

re-enters. Vocal soloists then give

out the Gegenliebe theme in

its original simplicity against

glittering keyboard figuration,

leading to the triumphant entry of the

chorus. From here onwards chorus,

piano and orchestra sustain a jubilant

blaze of C major, twice interrupted by

a dramatic plunge to E flat to

illuminate the word “Kraft” - power.

With the Rondo in B flat we go back

fifteen years or so to Beethoven's

early years in Vienna. All the

evidence, including the scoring

(flute, oboes, bassoons, horns and

strings), suggests that it was the

original finale of the B flat Piano

Concerto, published as No.2 with a

completely new final movement. After

Beethoven’s death the score was lost;

and the work was known only through an

arrangement, with a nnore flamboyant,

up-to-date keyboard style, by the

composer’s pupil Carl Czerny. The

original autograph turned up in the

archives of a Viennese church in 188

and was eventually published in 1960.

Much of the rondo sounds like a

slightly more decorous counterpart to

the familiar replacement finale,

likewise in buoyant 6/8 metre and

featuring syncopations and offbeat

accents. But in place of the central,

“developing” episode, Beethoven

inserts a gavotte-like E flat Andante

in the form of a theme and two

variations. This slow interlude has no

parallel in any of Beethoven’s

concertos. But his idol Mozart had

done something very similar in the

finales of two E flat Concertos (K 27l

and K 482), one or both of which were

almost certainly known to Beethoven.

Richard

Wigmore, 2004

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|