|

|

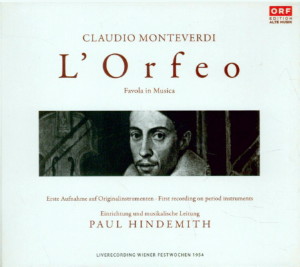

2 CD -

CD 3086 - (c) & (p) 2009

|

|

| Claudio Monteverdi

(1567-1643) |

|

|

|

|

|

L'Orfeo - Favola in

Musica, 1609

|

94'

46"

|

|

| - Prologo (Toccata e

Ritornello) |

4' 57" |

|

| - Atto primo |

14' 07"

|

|

- Atto secondo

|

23' 22" |

|

- Atto terzo

|

24' 14"

|

|

|

|

|

| - Atto quarto |

13' 49"

|

|

| - Atto

quinto |

14' 17"

|

|

|

|

|

| Patricia

Brinton, La Musica |

Gino

Sinimberghi, Orfeo |

|

Uta

Graf, Euridice

|

Gertrud

Schretter, Speranza |

|

| Norman

Foster, Caronte |

Mona

Paulee, Proserpina |

|

| Frederick

Guthrie, Plutone |

Waldemar

Kmentt, Apollo |

|

Ana

Maria Iriarte, Messaggiera

|

Auguste

Schmoczer, Ninfa |

|

| Dagmar

Hermann, Pastore orimo |

Hans

Strohbauer, Pastore secondo |

|

Wolfram

Mertz, Pastore terzo

|

|

|

|

|

| Die Wiener

Singakademie, Coro di Ninfe

e Pastori - Coro di Spiriti |

|

| Hans Gillesberger,

Einstudierung |

|

|

|

| Anton

Heiller, 1. Cembalo |

Hermann

Nordberg, 2. Cembalo und Regal

|

|

| Kurt

Lerpeger, Orgel |

Franz

Jelinek, Harfe |

|

| Karl

Scheit, Robert Brojer, Lauten |

|

|

| Paul Angerer, Kurt

Theiner, Nikolaus Harnoncourt,

Hermann Höbarth, Beatrice Reichert,

Eduard Hruza, Streicher |

|

| Karl Trötzmüller,

David Hermges, Karl Mayerhofer,

Josef Koblinger, Josef Spindler,

Hans Kraus, Josef Jakl, Johann

Tschedemnig, Wilhelm Pasewald,

Bläser |

|

|

|

| Paul Hindemith,

Einrichtung und musikalische

Leitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

Grosser Saal, Wiener

Konzerthaus, Vienna (Austria) - 4 giugno

1954

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live at Wienet Festwochen 1954

|

Producer / Engineer

|

Bernhard Trebuch

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

ORF "Alte Musik" - CD 3086 -

(2 cd) - 66' 40" + 28' 06" - (c) &

(p) 2009 - mono

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Alte

Instrumente oder Kopien

alter Instrumente

|

|

-

Italienisches Regal von 1556

(Leihgabe des Stiftes Lambach,

Oberösterreich)

-

Organo di legno (erbaut 1954

von Josef Mertin, Wien als

Kopie der Orgel der silbernen

Kapelle in Innsbruck)

-

Positiv (Gottlieb Henckhe

1728)

-

Cembali (Gebrüder Ammer,

Eisenberg, Thüringen)

-

Doppelchörige Laute (Mathaeus

Stautinger, Würzburg 1750)

-

Deutsche Kopie einer

italienischen Renaissancelaute

(doppelchörig)

-

Flautini (Dolmetsch, England)

-

Zwei Barockgeigen (18.

Jahrhundert)

-

Violen und Gamben: (aus der

Sammling Harnoncourt, Wien)

von Antoine

Veron, Paris 1735 - Ludovicus

Guersan, Paris 1742 - Anonym,

Brescia um 1580 - Jakob

Precheisen, Wien 1760

|

|

|

Fresh

tomatoes are not

enough to make good pasta

Claudio Monteverdi

about life and music

|

Born

in Cremona, home of

violin-makerr; "Suonatore di

Viola" and later

distinguished composer at

the Gonzaga court in Mantua;

for thirty years until his

death "Maestro di cappella"

of St. Mark's, Venice, a

musical metropolis and Mecca

for musicians and in whose

basilica, Santa Maria

Gloriosa dei Frari, "Il

divino Claudio" lies buried.

Over

three hundried and sixty

years later, Claudio

Monteverdi's music has lost

none of its timeliness. Not

only do the subjects of his

madrigals, arias and opera -

despair, love, desire,

jealousy etc. - continue to

stir our feelings but

stylistically his music

seems to possess the

immediacy that today's

listeners long for. The

recical of this most

influential of Italian

comèpsers would have been

unthinkable without Nikolaus

Harnoncurt's exemplary

performances.

Harnoncourt

(at this time member of the

Wiener Symphoniker) played

in the first performance of

l'Orfeo "on original

instruments", conducted by

Paul Hindemith in 1954,

alongside pratically the

whole - as yet anonymous -

Concentus Musicus Wien,

making this their unofficial

debut. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt's 80th birthday

and the appearance of the

first edition of l'Orfeo

four hundred years ago are

reasons enough for an

interview with the composer

who, together with his

colleagues, altered the

course of music.

We

may justly call the time

around 1600 a period of

upheaval in music. You

took an important part in

these changes. How did the

"nuove musiche" come

about?

You

could say that we were

living at the end of an era.

The style known today as

"Palestrina style", which we

called "prima prattica", had

reached its perfection, even

passed its zenith. Of course

we too had acquired this

style with its severe rules.

In Rome I was able to study

carious codices containing

sacred music by selected

Renaissance composers. As

you may perhaps know, I paid

homage to Nicolas Gombert,

one of the most important

masters of finely-woven

polyphony (and sadly almost

forgotten today) in the

"Missa in illo tempore" from

my 1610 collection of sacred

music.

Didn't

you want first and

foremost to prove to Pope

Paul V, dedicatee of this

publication, that you too

could compose in the old

style, with a post at the

Vatican in mind?

Prove?

I never had to prove

anything to anybody in my

life, except perhaps to

myself. I enjoyed every

hour, of the good as well as

bad times. Only the future

can show us which way the

present is pointing to. But

I'm starting to

philisophise. In fact, I

want to say something more

about our new compositional

style, the "seconda

prattica". We had no idea at

the time that we had

pratically developed a basis

for music that would last

until today.

Of

course it caused quite a

stir; just think of Maestro

Artusi's memorandum

[Giovanni Artusi "L'Artusi,

overo Delle imperfettioni

della moderna musica

ragionamenti dui", Venedig

1600] when my colleagues and

I had theown all the rules

overboard: dissonances on

strong beats, wide intervals

in individual voices,

violent changes of affect

and so on. But I don't want

to bore you with technical

details. They aren't the

most important thing! As

usual, there was no

theoretical basis for our

new music. But I have to

laugh a bit when I think fo

my fellow composers on the

other side of the Alps,

accustomed to thoroughness,

who looked for theoretical

principles for our new music

and even found some in their

teachings, making them up

with hindsight as it were.

Yes, people seem to require

certainties, rules of

engagement if you like, even

in composition, to earn

recognition without risk of

losing face.

In

1607 your brother

announced a book of yours

in which you set out and

defend the new

compositional style

"seconda prattica". Did

you ever get to write is?

I've

read many books, always been

interested in research and

have done research myself

into different things: I

devoted myself to alchemy

for example )I can admit

that now without risk). But

let me explain why it's

irrelevant whether this book

was written or not. I

greatly admire colleagues

who have tried to put

something down in writing

that's hardly possible to

explain in words. You'll

find lots to read about note

values, different rhythms,

tempi, intervals, harmonies,

instruments and much more. I

too treid to give as many

details and performing

instructions as possible in

my printed works. Just think

of the scores of L'Orfeo or

Il Combattimento di Tancredi

e Clorinda.

It

sounds as if you preferred

making music to writing

about it...

Everything

is done publicly today,

"transparent" is the word, I

think. You can reas about

the things that interested

me and my colleagues in my

writings, letters or

prefaces. For instance, if I

say about the performance of

Il Combattimento di Tancredi

e Clorinda that the audience

was moved to tears, then

that shows that I am

concerned about the

emotional reaction of my

listeners. In music we can

only hope for positive

emotions, we can't prescribe

them. Of course we also had

set-pieces, such as the

ciaconna, or devices such as

melting thirds in the voices

or violins.

By

the way, the great "Giovanni

da Firenze" (Jean-Baptiste

Lully is meant here)

introduced the ciaconna

almost as a standard element

in Louis XIV opera. But

still these are not recipes

for good opera, any more

than tearjerking scenes

alone make a good film, and

fresh tomatoes are not

enough to make good pasta.

What could I say about the

closing duet in my Ulisse,

except that it is a dance

that never wants to end,

joyous and melancholy at the

same time, like the Danube

Waltz, mirroring the peaks

and troughs of human

existence.

"L'Orfeo",

a "favola in

musica", is particularly

importasnt

among your stage works,

not all of which,

sadly, have survived. On

the one hand, lt's your first

opera and on the other,

it's the only one to have

appeared

in print during

your own lifetime.

1607,

the year in whlch L'Orfeo

was first performed, was a

memorable yeur in my life.

The crucial date was the

253rd day of that year, the

10th September, a Monday; my

beloved wife Claudia,

daughter of my colleague

Giacomo Cattaneo (a

viola-player, like myself at

one timo) diod on this

terrible day. She was a

singer at the Mantua court

and had suffered the death

of our daughter. but she

also bore our two

magnificent sons.

L'0rfeo

was first performed for the

"Accademia degli lnvaghiti"

on 24th February - a few

weeks before my fortieth

birthday - to great acclaim.

You can't imagine how much

tlme and nervous energy the

rehearsals had cost. As is

stlll often the case today,

many changes were made

(including mine) right up

until the dress rehearsal.

The end of the opera was

particularly affected; in

the printed libretto of 1607

the god-like singer comes to

a tragic end, as in the

mythological version. We

only decided on the

conciliatory "lieto fine" as

printed in the score at the

very last moment. I worked

very closely with the

librettist Alessandro

Striqgio on this matter.

Talking

about the score: I assume

that a desire

to impress

was one of the reasons for

its publlcation

two years after the first

performance.

Getting

a score into print around

1600 was no easy task. A

real challenge for the

printer Riccardo Amadino ln

Venice. Just thlnk of the

layout of Oefeo's "Possente

Spirito" aria with its many

diminutions. Of course

getting the score into print

was a matter of prestige,

for Francesco Gonzaga too,

to whom I dedicated the work

on 22nd August 1609. But its

publlcatlon was also very

useful for me and certainly

helpul for my candidature in

Venice.

The

first edition of

the opera throws up a lot

of question for us today:

on the one hand

there are discrepancies

between the instruments

listed in the "tavola" and

those called for in the

score, and on the other,

we still puzzle over where

the two instrumental

ensembles were placed for

example.

Like

Heinrich Schütz after me, I

tried to give as many

performance directions as

possible. The printed

edition of the work

naturally reflects details

arising from the opera's

first performance, although

I can’t recall them all

exactly now. But these are

all only aids to allow an

interpretation of the music

from the notes which moves

the senses, metaphysically.

These directions can still

be useful to musicians

performing my music in the

2lst century.

I've

followed the renaissance of

L'Orfeo on so-called

original instruments in the

20th century with great

interest. Although the

results all sound very

different from each another,

they do all attempt to get

to the bottom of the music.

We could talk for hours just

about the declamation of the

text. I'm particularly

pleased that my composer

colleague Paul Hindemlth

(who I believe I even heard

playing the cornetto in

Georg Schünemann's "Historic

Concerts" in Berlin) was the

person to lead the first

scenic performance on old

instruments since my time.

Josef Mertin (l904-1988) -

an early music

pioneer

in Austria - even built an

Organo dl legno for it.

People nowadays still use

organs with stopped pipes

for Italian music far too

often!

It's

worth noting that for this

special occasion Nikolaus

Harnoncourt contributed not

only the instruments from

his collection, but also

brought in like-minded

musicians. Practically the

whole Concentus Muslcus Wien

played, albeit anonymously,

in this performance. The

music world owes a great

deal of thanks to this

ensemble and above all to

its founder and director

Nlkolaus Harnoncourt.

Hindemlth’s

speech to the public in 1954

also reflects a lot of the

pioneer spirit: "Today, we

want to attempt to perform

this opera again under the

original conditions. We have

reconstructed the orchestra

exactly as he prescribes it.

We have done everything

possible to recreate the

original sound. What we do

may sum somewhat unusual to

you at first, but don't

forget, that is indeed how

it sounded at the time."

By

the way, did you keep

hearing the prompter’s voice

on the radio recording? That

lady must have been very

enthusiastic about the

performance, just as I was.

If

you were given the chance

to compose again, what

would you choose to write

- an opera, madrigals,

songs, sacred music, or a

genre which you neglected,

such as instrumental

music?

That's

a hard question, maybe even

impossible to answer. I

achieved and experienced a

lot, both professionally and

in my so-called private

life: For example, the death

of my daughter, only a few

months old, and that of my

wife soon after, or seeing

one of my sons arrested by

the Inquisition. But I also

spent many happy moments in

Venice, survived the plague

in the city in the early

163O's, and made a mark as

"Reverendo" in taking the

cloth.

It

certainly can’t be easy

writing music for the 21st

century. Today's public has

to take in such a flood of

information and is

overwhelmed with music. It's

everywhere, sounding and

pounding all the time. Then

there are so many styles,

quite unlike anything I had

in Venice in those days.

And

yet I notice, not without

pride, just how much today’s

listeners long for "simple"

means of music-making. Like

Henry Purcell, it was

important for me to achieve

a maximum of expression with

a minimum of means. Just

think of the Messenger's

appearance in L'Orfeo for

example.

Of

course Man is a rational

being, wanting explanations

for things that are

inexplicable. As far as

music is concerned, you

actually want to know today

how my music sounded back

then.

To

finish, I'd like to answer

you with a quotation from

Giovannino Guareschi’s "Don

Camillo and Peppone": "It

doesn't matter how it’s

written, but rather what

it’s like in your heart...»

Bernhard

Trebuch

(Translation: Roderick Shaw)

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|