|

1 LP -

MHS 1072 - (p) 1966

|

|

| 11 LP -

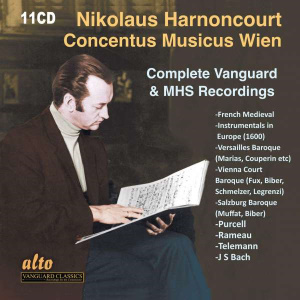

alto ALC 3145 - (p) & (c) 2022 |

|

Georg Philipp

Telemann (1681-1767)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

Parisian Quartets, Volume I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Premiere Suite in E

minor, Twv 43: e1

|

|

23' 21" |

A1 |

| - (Prelude - Rigaudon

- Air - Replique - Menuet - Gigue) |

|

|

|

| Concerto No. 1 in G

Major, Twv 43: G1 |

|

11' 44" |

B1 |

| - (Grave -

Allegro/Largo - Presto - Largo/Allegro) |

|

|

|

Concerto No. 2 in D

Major, Twv 43: D1

|

|

12' 29" |

B2 |

| - (Allegro -

Affettuoso - Vivace) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alice

Harnoncourt, Violin

(Jacobus Stainer, Absam 1658)

|

|

Leopold

Stastny, Flute (A.Grenser,

Dresden, middle of the 18th

century)

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Viola da gamba

(Jacobus Stainer, Absam 1667) and

Director |

|

Herbert

Tachezi, Harpsichord (copy

of the Italian

instrument circa 1700, by M.

Skowroneck)

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Casino Baumgarten, Vienna

(Austria) - 1966 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

-

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

| alto

- ALC 3145 - (11 lp) - 47' 40" -

(p) & (c) 2022 |

Prima

Edizione LP

|

Musical Heritage Society - MHS

1072 - (1 lp) - 47' 40" - (p) 1966

|

| Note |

| Library of Congress Catalog

No. 70-751714 |

|

|

Notes

|

For many years Telemann

intended to go to Paris. In 1737 he at

last found the time to visit that city,

where he remained for eight months. It was

here that the PARIS QUARTETS werefirst

performed and published.

The first two quartets are called

"Concerto Primo" and "Concerto Secondo,"

and represent the "modern" German school

of composition, circa 1730-1740.

These "Concerti", indeed, the quartets in

general, closely resemble the chamber

concerti of Vivaldi in the manner in which

each of the three instruments are used

individually and collectively. It is not

very likely that Telemann had heard

Vivaldi's chamber concerti (those for

flute, violin and continuo, of for flute,

oboe, violin, bassoon and continuo, some

of which are available on V-15 abd V-12),

since they were not published; nor,

judging from the single set of manuscript

parts, were they widely performed.

Telemann was, however, enpugh in tune with

the progressive spirit of his time to

write his own brand of modern chamber

music, and in so doing he captured the

spirit if not the style of his

contemporary in the South.

The first movement of the Concerto No. 1

in G begins with a slow introduction. The

following allegro combines elements of the

Baroque solo concerto with the newer quadri

(that is, music in which all parts are of

importance and the texture, though

frequently contrapuntal, is not

necessarily imitative in the Baroque -

Bachian - sense). Structurally, the

movement is divided into two almost equal

sections; the second being a slightly

modified version of the first, modulating

from the dominant (D major) to the tonic

of G. The short second movement, largo,

serves as an interlude and transition for

the fast movement in E minor, which

follows.

This movement is virtually a oncerto for

flute with accompanying instrunments.

There is also an interesting affinity

between it and the last movement of Bach's

Fourth Brandenburg Concerto (Bach and

Telemann were close friends for several

years. The latter was, in fact, Godfather

to Emanuel Bach). The following largo is

related melodically to the preceding one,

and like it, serves as a transition to the

next movement, allegro. There is an almost

Vivaldian quality about this movement. The

harmonies, rhythms (particulary in the

flute and violin parts) and some of the

ensemble writing show either a familiarity

with Vivaldi's chamber concerti or a

general familiarity with the more

progressive elements of his music.

Although the chamber concerti were not

published or widely performed in

Telemann's time, many of Vivaldi's

orchestral and solo concerti were in print

and well-known.

The Concerto No. 2 in D begins with a

motif almost identical to that employed by

Bach in his 2nd clavier concerto in C.

Like the "original" (unaccompanied)

version of Bach's concerto, the present

work has a constantly recurring ritornel

/theme), interspersed with contrasting -

solo - passages. Telemann's concerto,

however, utilizes the four instruments as

both soli and tutti, and it is a sure sign

of his ingenuity that one can easily

distinguish when the same instruments are

functioning as a part of the "orchestra"

or in a solo capacity. In the second

movement, Telemann contrasts the sonority

of the viola da gamba with that of the

flute and violin. There is a folk song

quality about this pastoral movement which

doubtless appealed to those who first

heard it as it does to us today.

Unlike the first movement, which is a

concerto for four solo instruments, the

last is virtually a flute concerto with an

occasional obbligato for a solo violin.

The movement is full of interesting

rhythms, and despite the four instruments,

it frequently sounds surprisingly colorful

and varied. Regarding length, intensity,

and diversity of thematic ideas, it is

wothout doubt the strongest movement of

the concerto.

While the first two "Concerti" represented

the "modern" chamber style of the German

composer, the next two quartets represent

the way a "young" composer wrote in the

style of the old-fashioned Italian sonata

da chiesa. For this reason, Telemann

called the third and fourth quartets

"Sonatas".

The difference between the sonata da

chiesa and sonata da camera

was essentially this: The latter was based

on dance movements while the former was

more serious and gad four movements

(slow-fast-slow-fast); the fast movements

being fugal. The slow, though

contrapuntal, were generally less complex.

By Telemann's time, the differences had

became less marked and composers often

referred to their trio sonatas as "sonatas

a tre".

The "Sonata Primo" is an example of a

"modern" composer writing in the style

of the past, albeit, using the

musical language of his own time. For this

reason, the openng movement, while slow

(in the manner of the sonata da chiesa) is

more lyrical than serious more homophonic

than contrapuntal. Onve again the

influence of Vivaldi is noticeable,

especially in the accompaniment played by

the violin and the gamba. In the old

sonata da chiesa, the first and second

movements (and occasionally all four

movements) were frequently based on a

common melodic motif. Such is the case

here: The first, fourth, and seventh notes

of the second movement are identical to

the first three of the first movements.

There is one difference, however, between

the old style sonata da chiesa and

Telemann's second movement. While the

former was nearly always a fugue, the

present movement is fugal without

being a true fugue. In other words,

Telemann wrote in the style of the past

without imitating in all details.

The third movement, andante, is based on

the counter-subject (secondary

melody) of the preceding movement - played

slowly and in a minor key. The rhythm of

the last movement is related to the dance

(specifically the gigue) - shades of the sonata

fa camera within the framework of

the sonata da chiesa. Melodically,

the fugal theme bears a subtle, but

definitive, relationship to the first

movement. More important, however, is the

fact that the first three notes of the continuo

part are identical to those played by the

flute in the first movement, so that we

see how, in his own way, Telemann wrote in

the style of the past while remaining true

to himself and his own time.

Douglas

Townsend

|

|

|

|

Telemann's

Paris QUARTETS for violine,

flute, viola da gamba and

harpsichord are some of his best

and most famous works. He seems

to have had a special fondness

for them, since he made special

mention of them in his

autobiography, which was printed

in 1740 in Mattheson's Ehrenpforte.

The best virtuosi of Paris had

obtained copies of the quartets

and invited Telemann to Paris.

He wrote: "...the admirable

manner in which the Quatuors

were played by the gentlemen

Blavet (cross-flute), Guignon

(violin), Forqueray son (viola

da gamba) deserves to be

descrobed, if this only could be

done by mere words. In short,

they attracted the attention of

the Court and the cuty and

contribuited to the general

esteem in which. I was held

within a short time." These

quartets (of which some are

presented on this record) were

so well received vy Telemann,

while still in Paris, wrote six

more quartets for the same

combination of instruments.

These were published as "Six

Nouveaux Quatuors."

Stylistically, the first six

PARIS QUARTETS consitute a

highly interesting work, since

Telemann demonstrates in them

(in three forms-sonata, suite,

concerto) the prevailing

Italian, French, and German

styles. In spite of this,

however, there is no trace of

any imitation, and the composer

has written in each of the

styles with the sure hand of a

master. As a matter of fact, the

choice of the four solo

instruments is mainly out of

deference to the Franco-German

taste, since at that time the

viola da gamba and the

cross-flute were by no means

popular in Italy, whereas in

Paris they were plainly the

instruments in vogue - togheter

with the violin, which was

coming into fashion. Telemann's

quartets are true soloist music,

in which each of the performers

has to display his full

technical virtuosity as well as

expressiveness in performance,

as each of them is equally

important.

No exact date of composition is

known, but it is assumed these

quartets were written between

1720 and 1730.

Although no autograph score or

parts have yet been found, the

first edition is known to have

been published in 1736 under

Telemann's supervision. It is

this edition which has served as

the basis for the present

recording.

In this recording, only original

instruments were used, i.e., the

violin and the viola da gamba

have the original measurements,

the original bar, especially

made cat gut strings, and are

played with bows dating from the

18th century. The cross-flute,

built by one of the most famous

masters of the 18th century, has

but one key; therefore, all

half-tones are achieved by cross

fingering. Besides the special

sound of the conic boxwood

flute, this has the effect of a

great variety of sound produced

by the individual notes. Thus,

they are given characteristic

features which cannot be

achieved by modern instruments.

The harpsichord is a true copy

of an old one. The strings are

plucked with quills, thus

producing a very clear and

brilliant sound.

The instruments:

- Baroque violin - Jacobus

Stainer, Absam 1658.

- Cross-flute - A. Grenser,

Dresden, middle of the 18th

century.

- Viola da Gamba - Jacobus

Stainer, Absam 1667.

- Harpsichord - copy of an

Italian instrument circa 1700,

by M. Skowroneck.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|