|

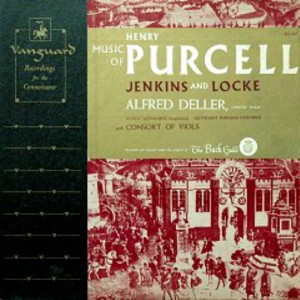

1 LP -

BG 547 - (p) 1954

|

|

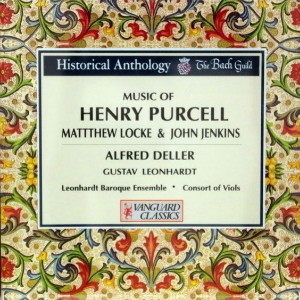

| 1 CD -

08 2029 71 - (c) 1994 |

|

| Music of Henry

Purcell, Jenkins and Locke |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Henry

Purcell - "Secrecie's song"

and "Mystery's song" from "The

Faerie Queene"

|

2' 58" |

|

A1 |

- Henry Purcell -

Fantasia in D for four viols, 1680

|

4' 03" |

|

A2 |

- Henry

Purcell - "Here let my Life"

from the Cantata "If ever I more Riches

did desire"

|

2' 48" |

|

A3 |

| - Henry Purcell -

Prelude, Air and Hornpipe, for harpsichord |

5' 31" |

|

A4 |

- Matthew Locke -

Consort of four parts, for viols (Fantasia,

Courante, Ayre, Sarabande)

|

9' 30" |

|

A5 |

| - Henry Purcell - "Here

the Deities approve" from the Ode "Welcome

to all the Pleasures" |

4' 38" |

|

B1 |

| - Henry Purcell - "Since

from my dear Astrea's Sight" from "Dioclesian" |

3' 56" |

|

B2 |

| - Henry Purcell -

Suite in D minor for harpsichord (Allemande,

Courante, Hornpipe) |

5' 22" |

|

B3 |

| - Henry Purcell -

The Plaint from "The Faerie Queene" |

7' 25" |

|

B4 |

| - John Jenkins -

Pavane for four viols (Ms. source, British

Museum) |

6' 04" |

|

B5 |

|

|

|

|

| Alfred Deller,

counter-tenor |

|

| Gustav Leonhardt,

harpsichord |

|

|

|

Leonhardt

Baroque Ensemble

|

Consort

of Viols

|

|

| -

Elizabeth Schaftlein, recorder |

-

Eduard Melkus, treble viol

|

|

| -

Gertrude Soukup, recorder |

-

Alice Hoffelner, treble viol

|

|

| -

Marie Leonhardt, baroque

violin |

-

Nicolaus Harnoncourt, bass viol

|

|

| -

Nicolaus Harnoncourt, baroque

'cello |

-

Gustav Leonhardt, bass viol

|

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Vienna (Austria) - maggio 1954 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

Seymour Solomon / Franz Plott

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Vanguard "Historical

Anthology" - 08 2029 71 - (1 cd) - 52'

42" (c) 1994 - ADD

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

- Vanguard "The Bach Guild" -

BG 547 - (1 lp) - 52' 42" - (p) 1954

|

|

|

Notes on the program (BG

547)

|

The latter half of the

seventeenth century brought important

changes to English music, changes that

were to stifle native expression for

many generations to come. Though

Puritan inhibitions were cast aside

with the accession of Charles II, art,

newly emancipated, yielded to the

extravagance and vanities of a

sovereign who had acquired strong

French leanings. Charles modelled his

court on that of Louis XIV; he

imported foreign musicians, created

his own Vingt-quatre violons du

Roi in which the "vulgar" violin

mingled with the soft-spoken viol, and

introduced lavish entertainments in

the French manner, setting the pattern

for the re-opened public theatres

where respectable old plays were

turned into glorified musical revues.

By the turn of the

century all resistance to the flood of

foreign influence was swept away. The

venerable John Jenkins whose chamber

music for viols had been breatly in

demand for over thirty years, now

wrote sonatas for the violins and

dance suites in the lighter vein. Even

the conservative Matthew Locke, "the

most considerable master of musick

after Jenkins fell off," and composer

of a "magnifick consort of four partes

after the old style which was the last

of the kind made... conformed at

last," says Roger North (Memoirs,

1728), "to the modes of his time...

and composed to the semi-operas divers

pieces of vocall and instrumental

entertainment, with very good

success...". Purcell's youthful

preoccupation with fantasias for viols

(he wrote fifteen of them in from

three to seven parts) twenty years

after Locke's "last," shows how deeply

rooted was this traditional English

form of music-making. Although in

idiom and technique they follow

earlier works of this genre, Purcell's

fantasias are infused with an

intensity of expression that is

obiously by the new style emanating

from Italy. His great dramatic works

were yet to come; in these he stands

alone as the only Englishman whose

creative genius was strong enough to

meet or surpass anything that came

from the continent. Had he lived

beyond his brief thirty-six years, the

story of English music might well have

been different.

The Restoration theatre given a new

lease on life, revived Shakespeare,

and other renowned Elizabethans,

"adapting" them to the taste of the

time. Every opportunity was taken to

make use of song, dance, and the

elaborate machinery of the Parisian

stage. Purcell's Faerie Queene,

based on Shakespeare's A Midsummer

Night's Dreams, is such an

adaptation. It is a masque-like opera

and a complete distortion of the

original play. The anonymous

librettist has rearranged scenes,

invented verses for musical interludes

and generally altered and disfigured

Shakespear's text so that it has

become hardly recognizable. Yet for

such a vehicle Purcell provided some

of the finest and most effective music

he ever wrote for the theatre. The

piece was first produced in 1692. The

wit and charm of the various

spectacular and choreographic episodes

have fascinated modern producers, who

since the rediscovery of the

manuscript in 1903 have mounted a

number of successful revivals in

England, Germany and Belgium. An

interesting re-adaptation on the work

by Constant Lambert in collaboration

with Professor E. J. Dent and others,

was presented with the Sadler's Wells

Ballet at Covent Garden in 1946.

Mystery's Song and Secrecie's Song

appear seccessively in Act II of the Faerie

Queene (Purcell Society Edition,

1903). The former is accompanied by

'cello and harpsichord, the latter by

two recorders and harpsichord. The

Plaint was added to Act V for

the opera's revival in 1693. It is a

song of pathos sung over a chromatic

ground bass with a beautiful obbligato

line for violin - a miracle of

sustained expression.

Of the four Purcell Odes

written for St. Cecilia's Day, the

earliest and one of the best is Welcome

to all the Pleasures (1683). In

the song Here the Deities approve

which follows the first chorus, a

three measure ground, played eighteen

times, provides a bass for the air as

well as for the long instrumental

postlude. An arrangement of the song

appeared in the second part of Musick's

Handmaid (1689) under the title

of "A New Ground."

Though the harpsichord solo pieces of

Purcell are not among his important

work they are nevertheless

characteristic and individual. The

most interesting are the little Suites

published posthumously by Mrs. Purcell

with a dedication to Princess Anne and

entitled "A Choice Collection of

Lessons for the Harpsichord or

Spinnet," London, 1696.

The air Here let my Life comes

from the chamber cantata If ever I

more Riches did desire. It is

scired for violins with a continuo and

is a beatiful example of the aptness

of text and music. Since from my

Dear Astrea's Sight was

apparently written for the revival of

the opera The Prophetess, or

the History of Dioclesian, in

1691 or 1692 and seems to have been

intended for inclusion in the last

act.

Sydney

Beck, Music Division, New York,

Public Library

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|